Michael Walters

Notes from the peninsula

Director: Roseanne Liang

Horror stretches across many genres, and you can’t always know in advance how horror-y a film is, so with Shadow in the Cloud we are in war-action-horror territory, in that order. Maude Garrett arrives at an about-to-takeoff B-17 in 1943, presenting papers to the crew that let her and her top secret cargo onboard. The men are abusive and dismiss her to the gunner’s position beneath the plane, separating her from her mysterious bag. When Japanese fighters attack, and a creature clinging to the outside of the plane starts pulling it apart, Maude has to escape and somehow get herself and her precious cargo to safety.

Okay, there’s no escaping it—the first half is an unpleasant exercise in controlled misogyny, with our lead Maude stuck in an enclosed space having to listen to the crew on the radio say horrible and disturbing things about her. It goes on way longer than it needs to, and while you could argue it’s necessary for the emotional release of the film’s second half, and conditions were undoubtedly much worse in the nineteen-forties for women in the military, it almost made me turn it off. Chloë Grace Moretz is given plenty of emotional range to work with and was charismatic enough to keep me onboard, and the reward is a halfway handbrake turn where Maude becomes an Indiana Jones-type character in a swashbuckling adventure.

The horror is primarily in the gremlin ripping the plane to pieces mid-flight, but is also in the gross misogyny of the male characters. It scrapes into #31DaysofHorror, but it’s at the outer limits. A mixed experience.

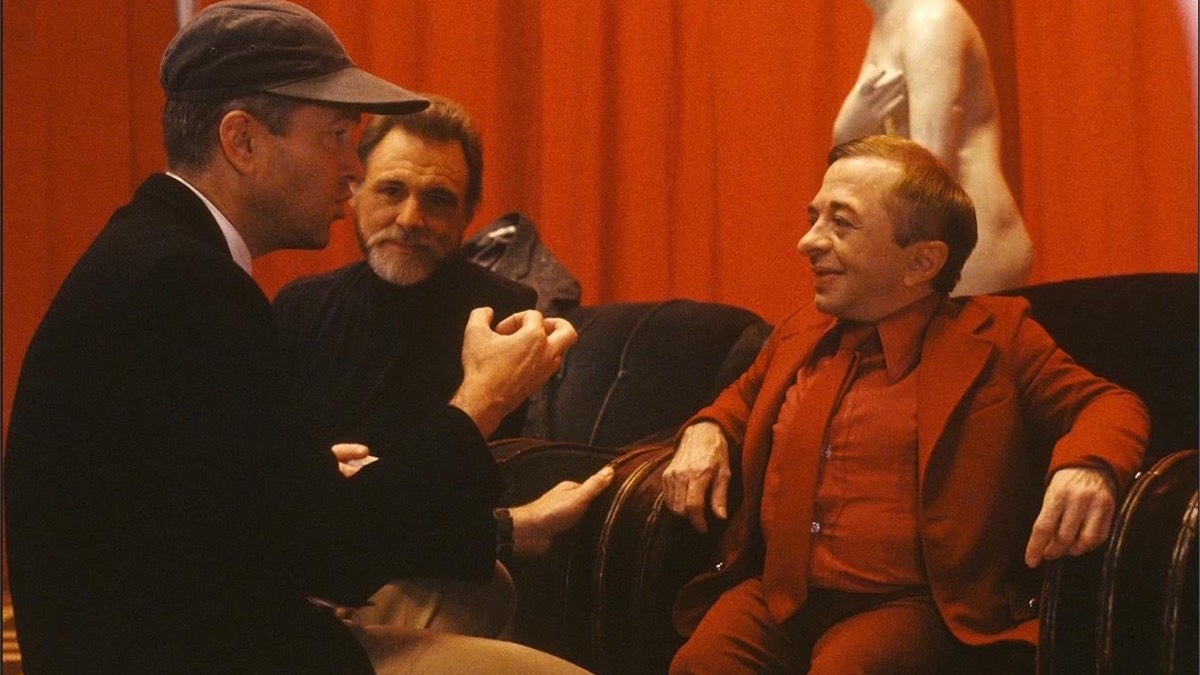

Director: Mario Bava

Lisa and the Devil lives in one of the lesser-known corners of the Mario Bava-verse. Telly Savalas as the possible devil Leandro is an amusing presence, and if he is not particularly devilish, the dream-like plot definitely is. Lost tourist Lisa comes across Leandro in an unnamed European town, and she is immediately afraid of him—he looks like the devil she‘s just seen in a fresco on a church wall. That devil carried the bodies of the dead under his arms, and Leandro is picking up a dummy he’s having repaired to carry home. She tries to return to her group, but the streets become maze-like and darkness falls, so she is forced to ask for a lift with a rich couple and their chauffeur. The car breaks down at the door to a gothic manor house, and when they knock for help, it is answered by Leandro, who invites them inside.

And it just gets more complicated from there. There’s a family, and mannequins, and ghostly knockings, and a dream lover that Lisa thinks she knows, and a killer in the house, and lots of running through enormous abandoned rooms. It all looks ravishing and has plenty of fun performances, but it’s more of a ghostly mystery than particularly frightening, an adult fairy tale. The acting has a hammy, knowing quality which, along with the fantastical tone, constantly reminds the viewer that this is an artifice. I would have enjoyed it more if it had ended on the penultimate scene, but Bava insists on a silly final twist that slightly spoils it.

The Addiction (1995)

Director: Abel Ferrara

After two quite light films, Abel Ferrara’s The Addiction is a hard turn downwards into the circles of hell. Kathleen is studying for a doctorate in philosophy in a grungy, black-and-white New York, where the streets are lined with hustlers and junkies. She is disillusioned with academia, obsessing over the horrors of German and American war atrocities, but unsure what to do about it. One night she is pulled into an alley and bitten by Casanova, a female vampire, who mocks her for not putting up more of a fight. As she slowly transforms into a vampire herself, her contempt for humanity grows, her appetite for human blood increases, and she develops a more practical and horrific philosophy to exist by.

This is a film thick with social commentary, philosophy texts and existential ideas. The first images we see are piles of dead bodies from the Holocaust and Vietnam, and a class of students watching on a projector screen. For Kathleen’s friend Jean, it’s all academic—she is able to eat her sandwich while reading textbooks on the subject—but Kathleen feels the violence on a deeper level. She hates that American politicians look for scapegoats so justice can be seen to be done and the country can move on. Most people want to forget about it. The collective guilt is unbearable, so it is repressed, and the source of the violence remains seeded beneath the surface. The vampires haunting New York talk about evil and sin, but they are also the violent shadow of the collective unconscious.

The final feast, where the newly-graduated Kathleen eats her professors, must have influenced the opening of Blade, where the innocent party-goers are really food. Ferrara would probably say nobody is innocent, and that most of us are, in Casanova’s words, collaborators. Vampires and nihilism go hand in hand, and addiction is can lead to self-destruction, but perhaps there are ways to better harness our human appetites for violence. Ferrara is asking us to do something about it.

Jakob’s Wife (2021)

Director: Travis Stevens

The irrepressible Barbara Crampton and Larry Fessenden star in this story of a woman’s mid-life crisis being super-charged by an encounter with a vampire. Anne lives a quiet life as the wife of minister Jakob, who is a pillar of their local community. When she invites old flame Tom to submit a tender for a local project, he tempts her into a kiss, but a vampire called The Master intervenes, leaving Anne bitten and with a new appetite for human blood. Her burgeoning confidence challenges Jakob, who just wants her to keep playing the role of dutiful minister’s wife.

Stories of women’s mid-life crises are hard to come by. I love the sly humour of Jakob’s Wife, and Anne’s glee as she loosens her marriage shackles is infectious. Her vampire appetites brings chaos into Jakob’s life, upending all of his rules and expectations, and anyone feeling the constrictions of mid-life and marriage, its duties, and having to come to terms with death being closer than youth, can empathise with both of them. The social contracts we abide by can choke us if we don’t pay attention.

When Anne tells Jakob what she really wants, his initial responses are limited to wanting the whole thing to go away, and he resorts to sullenly clearing up the bloody mess Anne makes with her victims. They love each other, but Anne eventually has to answer the question: does she always just want to be known as Jakob’s wife?

Werewolves Within (2021)

Director: Josh Ruben

To kick off this year’s #31DaysofHorror I chose Werewolves Within, a comedy-whodunnit-horror based on a Ubisoft video game. I heard screenwriter Mishna Wolff (perfect name) and director Josh Ruben talk about making it, and it sounded like a fun October opener.

Newly appointed forest ranger Finn arrives at the tiny outpost of Beaverfield, in the snowy woods of Vermont. Postal worker Cecily introduces him to the cartoonish locals, almost all of who want to sell their homes to an oil company for a big payout, but the deal is being held up by a handful of refuseniks. The hotel owner’s missing husband is found partially eaten, the power lines are cut, and as the many bristling resentments become murderous, Finn has to work out who is doing the killing, and whether it really is a werewolf.

I didn’t guess the killer, but then I didn’t twig it was a whodunnit until quite a way in, so that’s no surprise. The first half was much more of a broad comedy than I was expecting, with a dash of rom-com thrown in, but the horror vibe got stronger towards the end. I loved the snow and the locations, especially the deserted bar with the pinball machines and jukebox, and Cecily is a playfully subversive take on a manic pixie dream girl. For #31DaysofHorror, I wish it had more werewolves in it, but there were a couple of good jump scares, and it was never boring. A decent start.

Horror AND sex!

Here we go again, with my fourth #31DaysofHorror extravaganza/exhaustathon. This year I just want a reason to watch a lot of horror films. Here are the rules I’m playing by:

- one blog post about a horror film on each day in October

- the posts must be published in the order the films are watched

- the film must either be completely new to me or not seen in at least twenty years

- to stay healthy, the challenge starts twenty-one days before the first post is published

I’ve talked about this before, but watching these sorts of films makes me feel like I’m hanging out with my dad. When I was eleven years old, on a rainy afternoon in a Saundersfoot caravan park, to stop me complaining about being bored, he let me read his copy of Salem’s Lot. On the same holiday, in a Tenby second-hand book shop, I bought Guy N. Smith’s Night of the Crabs because the fantastically lurid cover grabbed me, and in the back of the car on the way home, with a furtive look around to make sure nobody could see, I came across my first literary sentences about sex. Horror AND sex! (Let’s ignore that it was about crabs.) I was off to the races.

Around the same time, a VHS recorder arrived in the house, and the video shop became one of my best friends. Both my parents were incredibly liberal in what they let me watch—thrillers, horror, sci-fi, fantasy—and my dad started to introduce me to less well-known films, and eventually I discovered Moviedrome, that beloved late night BBC Two haven for cult film lovers.

Genre stories were my magic carpet. It’s shocking what I was allowed to watch (and read), but those films kept me company. They were a comfort and an outlet for my adolescent horror show. Later, once my son was born, I couldn’t watch horror films, because the world had become scary enough, and post-9/11 there was a lurch towards torture porn, which I hated. I only returned to horror recently, in my late mid-forties.

The 2020 challenge was a lot of fun. I did that one to stop the Trump/Brexit/Covid shitshow from filling up my head (there’s a list of the films from 2018 and 2019 there too). #31DaysofHorror started as a dare to myself, then became a protective mechanism against watching too much news, and now seems to have settled into a fun ritual. I think I know what my first film this year is going to be.

Auguste

The Three Colours trilogy marked my move from July into August, and amusingly the fledgling judge in Red is called Auguste. I don’t know why I chose Three Colours: Blue—actaully, I do remember. I ordered my iTunes movies by date purchased, and it was the oldest film I still hadn’t watched. May 2014, so over seven years ago. I had the trilogy as a VHS box set in the mid-nineties, along with Miller’s Crossing, Alien, Lone Star and Die Hard, and I would lug them in carrier bags as I moved between my grotty flats. That’s a pretty accurate reflection of my taste now too. Not the grottiness but the range of genres.

Twenty-five years later, Blue blew me away, White was pristine (but hard to love, lol), and Red was the perfect finale. I watched White and Red together, today, just before I started this post, and that allowed me to see all the little character overlaps. The thing I love most about Krzysztof Kieślowski is the way he manages to show you something important and new, with feeling, when you are not expecting it, usually through imagery, but also connections between events, lines of dialogue, and ideas. He doesn’t give you it all on a plate. He leaves space. A true act of artistic generosity.

Inland Empire

Director: David Lynch

Release year: 2007

In Inland Empire, which is also a massive region of land with nebulous boundaries east of Los Angeles (just saying), married actress Nikki Grace wins a part in a film opposite known philanderer Devon Burk. On the first day on set, director Kingsley Stewart tells them he has just found out the script is actually a remake of a German film called 47, which was never finished because the two leads were murdered. Nikki’s husband Piotrek is controlling and jealous, and he threatens Devon, but Nikki and Devon start an affair anyway. Then shit gets weird.

There are multiples stories unfolding, in Los Angeles and in Poland, in Vikki’s real life, in the film they are making, and in the apparently cursed film they are remaking, which Vikki seems to move in and out of. It quickly becomes clear we can’t know for sure where we are, and there is the extra quality of the DV camera Lynch used, whose grainy, home video picture and poor sound quality constantly reminds us we are watching Lynch make a film.

It’s an unusual and meta experience to say the least, but after three hours, as the end credits roll, I find I’m crying, because of the joyful music, yes, and because I’m exhausted, definitely, and because this is probably David Lynch’s last film, and it’s the end of my David Lynch project, but the biggest reason I think is that if it’s possible for someone to make Inland Empire, this ridiculous, epic, surreal, sometimes dull, sometimes exhilarating, contradictory, confusing, experimental art film, then honestly, and this is quite an insight after a month of Lynch’s work, and probably what I was hoping to realise, anything is fucking possible.

Mulholland Drive

Director: David Lynch

Release year: 2001

The pattern David Lynch tends uses in his more archetypal work is again on display in Mulholland Drive – events organically unfold, the images are striking, the narrative is confusing, characters are not who they seem to be, and in the last twenty minutes he reveals what’s really going on, which is then open to even more interpretations. It’s a heady formula that allows him to explore the psychological themes that clearly fascinate him.

I was pretty frustrated with Mulholland Drive until the last act when, true to form, he performs his magician’s trick. It was created as a pilot for a television series with NBC, which the studio didn’t like, and Lynch then was given money by StudioCanal to finish it as a film. It feels like it was meant to be open-ended, with many elements reminiscent of Twin Peaks, but the ending he came up with does a pretty wonderful job of sealing it in movie form. Like Fire Walk With Me and Lost Highway, the story hinges on the main character’s psychological reaction to trauma, in this case an alternative reality that of course cannot last.

There is only one film left in my May project to watch all of David Lynch’s films. I feel sad the project is ending soon, and there is no more film Lynch to explore, but he’s still making television series, and he might make another movie. He’s not dead yet. I suppose I prefer the Lynch who has to constrain himself to two hours than the one who lets himself sprawl – which takes us neatly into Inland Empire.

The Straight Story

Director: David Lynch

Release year: 1999

If David Lynch were trying to somehow redress all the darkness of his earlier films in one go, then he would make The Straight Story. Like The Elephant Man, it’s straightforward and forgoes the dreams, fantasy sequences and excess of Lost Highway, Twin Peaks and Blue Velvet. It really is a pure thing. Old age is investigated with a tender eye, and the hero, Alvin Straight, is wise and practical.

When he hears his brother has had a stroke, Alvin sets out on an odyssey to travel the three hundred miles to his brother’s house on a lawnmower. His eyes are too poor to get a driver’s license, but we realise the lawnmower has become a choice when he is offered a lift but refuses it. As he says, he wants to do it his own way, which you get the impression he has done his whole life.

Everyone he meets is good-hearted, and the handful of conversations he has on the road each reveal something about his nature, or his past. His hard-won wisdom rubs off on people. He very much reminded me of my grandfather – quiet, creative with mechanical things, a problem solver, stubborn, sometimes abrasive, and carrying memories he struggles to speak of. To me The Straight Story is a lovingly told expression of appreciation and respect for this type of man, made even more poignant in knowing that that generation, who fought in World War 2, are now almost all gone.

Lost Highway

Director: David Lynch

Release year: 1997

Lost Highway is a puzzle. It opens with a jealous husband who thinks his wife is having an affair, and ends with a deadly resolution, but what happens in between is ambiguous and complicated. There are unsettling video tapes left on doorsteps, threatening hallways that seem to swallow characters up, dream sequences that might be memories, a menacing man who is in two places at once, and a character switch at the end of the first act that takes the film in a completely different direction.

After following intense jazz saxophonist Fred Madison, we move into the life of laid back mechanic Pete Dayton who falls for Alice, a doppelgänger of Fred’s wife. The film becomes a noir mystery in this second act, as Alice seduces Pete, and draws him into conflict with the violent and unpredictable Dick Laurent.

Lynch loves psychological stories, and has said that he was thinking a lot about the OJ Simpson trial at the time he was writing Lost Highway, in particular how a man could kill two people and then carry on with his life as if nothing had happened. Twin Peaks’s Laura Palmer did a similar split within herself to cope with trauma, and that is the key to Lost Highway. Characters are archetypal, more than one character is not who they appear to be, and in the end Fred’s psychological problem of jealousy is solved.

In an interview with American Cinematographer, Lynch talks about how his ideas come into being, which I think shines a light on the unique quality all of his films have:

When asked to explain how his rather unique thought processes conspire to conjure up his cinematic visions, the director assumes a sincerely thoughtful expression. “Everything sort of follows my initial ideas,” he offers. “As soon as I get an idea, I get a picture and a feeling, and I can even hear sounds. The mood and the visuals are very strong. Every single idea I have comes with these things. One moment they’re outside of my consciousness, and the next moment they come in with all of this power."

The complexity of Lost Highway might come from this process, where powerful images force themselves into Lynch’s work, and he has to work out what to do with them. It might be impossible to rationally explain it all. Sometimes the image requires a leap of faith, by the filmmaker and the audience.

Director: David Lynch

Release year: 1992

A howl of pain from Laura Palmer, the murdered girl that opened the TV series, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me is difficult, heavy, hard to watch in places, and grapples with incest, rape, drug-taking, murder, domestic abuse, and the psychological consequences. Perhaps we get the opening half hour with the citizens of nearby Deer Meadow to connect us with the humour and quirkiness of the TV series, although these people have an obnoxious streak, but it does feel odd, like a different film. By the end, it feels like another universe.

The film is brutal and haunting, but I found it frustrating that Lynch felt compelled to make it at all. It tries to explain and wrap up the mysteries of the TV series, but it doesn’t quite stand on its own as a piece of art. If I hadn’t seen the first season of the TV series, and know the ending of the second, I don’t know how much of this would have made any sense.

Having said all of that, as a telling of the story of a victim of incest, it’s mature, emotionally smart and absolutely devastating. I just wish that either there were less decorative aspects of the TV series, or they were woven in more coherently. However, there are shots and scenes in this film that I will never forget. It’s a flawed masterpiece.

Wild at Heart

Director: David Lynch

Release year: 1990

After Blue Velvet, Lynch made the first season of Twin Peaks, then pivoted into Wild at Heart. It’s a series of deliberately melodramatic, hyper-violent and sexual scenes stitched together into a road movie, with a tenuously-made connection to the Wizard of Oz.

The performances are amazing, but I found the overall effect rather numbing. I didn’t really care about Sailor and Lula’s relationship – in fact, I wanted Lula to strike out on her own, Sailor being mostly a liability. Lula uses Sailor’s violence to escape the clutches of her shockingly possessive mother, who sets off a pack of creatively grim villains to kill Sailor and bring Lula back home. The most interesting part of the film is the middle section, where the sexually ravenous couple begin to open up to each other, and the bad omens mount, including a haunting scene where a woman is wandering near a car crash, not knowing she is dying, looking for her things in the sand.

Lynch said he wanted to make ‘a really modern romance in a violent world – a picture about finding love in Hell’, and I think he succeeded. For me, the ironic tone and melodrama took me too far out of the film, and I found myself sometimes bored, which I hesitate to say about a film with such an enviable reputation. I also have to remind myself that there was nothing like this at the time, and Wild at Heart’s influence can be seen in Reservoir Dogs, True Romance and Pulp Fiction.

Wild at Heart takes Lynch in a different direction. I didn’t love it, but it’s an important stepping stone. Everyone in the film seems to be having fun, and it’s a perfect palette cleanser after the double hit of slow-paced small town darkness in Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks. This is David Lynch on the road and cutting loose.

Blue Velvet

Director: David Lynch

Release year: 1986

I was nervous going in to Blue Velvet, more so than any horror film. It has a fearsome reputation but is also culturally beloved. Dennis Hopper’s over-the-top performance has become iconic, and its themes foreshadow those in the massively popular Twin Peaks. Some films become intimidating over time as more and more is written about them, but it was what I knew of Hopper’s Frank Booth and the sexual violence that put me off watching it for so long.

Blue Velvet is a brilliant film, as outrageous and disturbing as I’d heard, and about many things – innocence, curiosity, darkness, tenderness, violence, growing up. Jeffrey comes home from college because his father has had a stroke. He finds a severed ear on waste ground and takes it to the police. Detective Williams tells Jeffrey not to ask any more questions, but Jeffrey’s curiosity sends him on an odyssey into the underbelly of his seemingly picture book hometown.

Lynch knows his unconscious onions. With Jeffrey’s real father out of action, Detective Williams is a kindly replacement, just as Frank Booth is a sadistic one. The film is full of opposites like this. Jeffrey falls in love with Williams’s daughter, Sandy, but is sexually attracted to the damaged and dangerously masochistic Dorothy, who Frank is blackmailing into sexual slavery. Jeffrey has several opportunities to withdraw from the mystery, but he keeps going, thrilled by the hunt and illicit sex. He wants Sandy and Dorothy, but reality hits when Frank forces him into a hellish drive out of town, where at one point, Frank says to Jeffrey, ‘You are like me.’ Through the film, Jeffrey absorbs some of Frank’s cruelty, hitting Dorothy during sex, and eventually shooting Frank in the head. From a Jungian perspective, by the end Jeffrey has endured a great deal of suffering, but is rewarded with the integration of a large chunk of his own shadow.

Jeffrey’s whole adventure could also be read as a distraction from the grief and fear that his father might die. At one point the camera goes into the severed ear, and at the end it pulls back out of it. Was everything in between a dream?

There’s a fascinating episode on curiosity, by the This Jungian Life podcast, describing curiosity as an innate human drive that can be both useful and destructive. Jeffrey’s voyeurism and passion for the mystery makes him take enormous risks, and by the end he has used what he has learned from Frank and Dorothy to clean up the darkness in the town and create for himself a place of relative contentment. He wrestles with his own violent, sadistic and masochistic impulses, and comes to appreciate how the robins of love from Sandy’s dream also eat fat bugs. Love and darkness are intimate. As Sandy says, ‘It’s a strange world, isn’t it?’

From a writing process perspective, I love how it was conceived by Lynch years earlier as a vague feeling, and a title, to which he later added the image of an ear in a field, and the song Blue Velvet. He considered the screenplay he wrote from those seeds unpleasant and not good enough to make, but after directing Dune, he came back to it. He added a voyeur discovering a murder mystery, and the scene where Dorothy emerges beaten and naked on the street was something he actually experienced as a child.

In Blue Velvet, Lynch successfully created something culturally important and resonant that was also deeply personal. He used his curiosity about his own inner world to create a vivid and vibrant piece of art. That’s inspiring.

Dune

Director: David Lynch

Release year: 1984

I went into Dune thinking I would see something the critics were missing – I mean, how could the director of Eraserhead and The Elephant Man direct a complete dud? – and… it’s so over-the-top, it manages to not be awful.

The Lynch love of dream sequences, moons, and faces in the sky is all here, and it has Eraserhead’s queasy body horror in the villainous Baron Harkonnen, who is so deliberately diseased, vile and pantomime camp, I can’t decide if he is the worst or best part of the film. Sting does inject some actual menace, but then he appears comically greased and almost naked in a winged cod piece, to his father the Baron’s perverse delight, and spoils it.

Having said that, there is plenty to enjoy in the baroque and sometimes surreal visuals, and a few performances are excellent, especially Max von Sydow as Doctor Kynes, the Fremen liason, and Francesca Annis as Lady Jessica. But the plot is a real mess, and the final half hour is painful.

Lynch wrote seven drafts of the screenplay, his final three-hour cut from the final draft was slashed to two hours at the insistence of producer Dino De Laurentiis, and scenes had to be reshot to make sense of it all. He still declines to talk about the film in interviews. The film bombed, and when Lynch in later life talked about the importance of keeping control of the final cut, he must surely be referring to his time with Dune.

The Elephant Man

Director: David Lynch

Release year: 1980

The Elephant Man is as traditional and straightforward as Eraserhead is surreal and obtuse. Both are black and white, and Lynch does use some dream imagery in The Elephant Man, but they’re at opposite end of the narrative spectrum. When you finish The Elephant Man, you are in no doubt about what you’ve just watched and what it means.

The camerawork is precise and every shot is pristine and artful. The story is emotional and mature, with an important message, and the ending is majestic. I appreciated it, and I felt it deeply, but everything is exquisitely on the surface. I’m finding it hard to write about, perhaps because compared to Eraserhead there is so much less room for interpretations. Anyway, I loved it, and I can’t imagine wanting to watch it ever again.

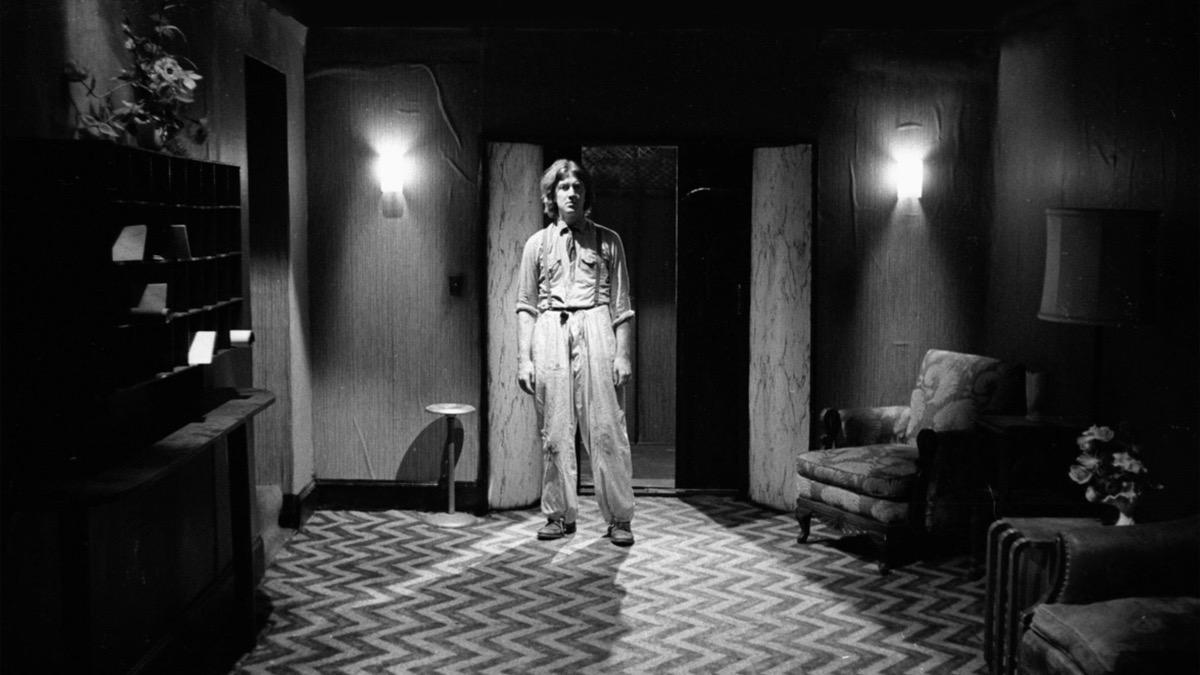

Eraserhead

Director: David Lynch

Release year: 1977

It’s surprisingly hard to see David Lynch’s Eraserhead in the UK, which means it is easy to avoid. To me the title was abstract and off-putting, as was its reputation as one of Lynch’s most experimental, gruesome works. The iconic black-and-white picture of Jack Nance as Henry Spencer always reminded me of Bride of Frankenstein and an older, artier film than I ever seemed to be in the mood for.

To watch it I had to buy a German Blu-ray, which came with an excellent documentary, Eraserhead: Stories, and all of Lynch’s short films up to that point. I also found a Kickstarter-financed interview film, David Lynch: The Art Life. Between those two documentaries you get a good sense of the man as an artist and filmmaker. He’s quite something. His ideas about art and the process of making really chime with me. There is also, of course, the video of him comparing the creative process to fishing, which is fun.

Lynch directed ten films – Eraserhead, The Elephant Man, Dune, Blue Velvet, Wild at Heart, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me, Lost Highway, The Straight Story, Mulholland Drive and Inland Empire – and wrote them all too, apart from The Straight Story, which was written by Mary Sweeney and John E. Roach. He’s a true auteur.

I find his voice soothing, even though it has a grating quality, possibly because he seems like such a gentle, curious soul, and he talks directly, with great enthusiasm, about what he finds interesting. If I’m honest, this is the other reason I chose David Lynch right now – I intuitively know he has something that I need in my own work. Perhaps I’ll have worked it out by the end of the month.

Anyway, Eraserhead – reader, I loved it. It was so imaginative and pure and watchable and laugh-out-loud funny, which I didn’t expect at all. It’s a psychosexual puzzle about the horrors of unplanned parenthood, marriage, intimacy, capitalism, poverty, dreams – you can take it any direction you like. Jack Nance’s tragicomic helplessness and existential anxiety reminded me of comedic actors from the silent era. More than once he made me think of Oliver Hardy. The sound design is incredible, and the visuals are endlessly inventive.

I don’t want to write about what I think the film means. It’s going to stay with me, and there’s no point repeating what others have said. Watch it and make up your own mind. More than the film, the thing I’m most struck by is Lynch himself – how he works with his unconscious mind and processes his life through art. He says in one of his interviews that the past is always in the present, which I have also found to be true.

I’m looking forward to sitting with him, in my mind, at his studio in the Hollywood Hills, for the rest of the month.

Writing gland

Stephen King’s On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft is one of those books I keep coming back to, this time to stimulate my first draft writing gland and get my novel moving again. I’d run aground at twenty thousand words. King’s advice? Write every day and keep going. Thanks, Stephen. Annoyingly, he was right, and I wrote 500 words every day this week. Yay, me.

Even with this blockage removed, and perhaps because the blockage wasn’t there to fixate on, it was a tough week, the hardest emotionally since the pandemic started. This time we know it will be months, not weeks. Outside it’s cold, dark and icy, and I turn forty-eight in March. The life clock is ticking.

To inject some fun into things, I watched Tentacles, a B-movie Jaws ripoff starring John Huston (!), Shelley Winters (!!), Henry Fonda (!!!) and Bo Hopkins (?!). It was much worse than I hoped. Where [Piranha had Joe Dante to add some humour and irony]({% link _posts/2020-31-days-of-horror/2020-10-10-piranha.md %}), Assonitis is seemingly incompetent. All those great actors wasted. Where did the money come from to make this? I’m glad I watched it though, because I never take a complete punt on a film like this, and now I know what a terrible B-movie looks like.

Clearly a glutton for punishment, I went Thai aquatic horror next with Brian Yuzna’s Amphibious, a.k.a (which I only realised after a completely unnecessary battle axe was hurled at the camera) Amphibious 3D. My eyeballs were still seared from Tentacles, so as poor as the script and acting were, this felt like a banquet of cinema in comparison. The giant sea scorpion was memorable, and the Miskatonic University sticker on marine biologist Skyler Shane’s laptop made me smile. It had an odd tone, like a gory mix of Big Trouble in Little China and Pirates of the Caribbean. I can’t recommend it.

After those two stinkers, and also being primarily a writer of novels, it seems wrong to bring in 2020 Booker shortlisted Real Life here, but that’s how the week unfolded. Like real life, Real Life is impressive but left me frustrated. The book’s protagonist, Wallace, is similar to me in some ways (emotionally damaged, male, scientist) and not in others (he is black and gay). Over an intense weekend, we see his previous experiences and assumptions spark against those of his friends and colleagues. My problem with the book is too many times I felt overwhelmed by, and impatient with, the cattiness, games and histrionics of his friends and peers. Perhaps it’s where I am in my life. I’m glad I’m not in my twenties anymore. Perhaps I’m jealous — he didn’t even want to write a novel and wrote it in five weeks just to get his agent off his back. Damn it, Brandon, at least pretend it was hard.

It is, of course, Giallo January, and like Taylor, Dario Argento is prolific (yes, I see the pattern in my choices here). After Argento’s debut masterpiece The Bird With the Crystal Plumage came out in 1970, he released two more films in 1971 — The Cat o’ Nine Tails and Four Flies on Grey Velvet. The former is a sprawling crime mystery set in Turin and has a blind ex-journalist join forces with a reporter on a big newspaper to solve the murder of a scientist at a genetic research facility. The latter is more in keeping with Argento’s other work, where a serial killer torments a rock musician and makes him question his sanity. There are red herrings galore, and lots of over-the-top and super-camp side characters, but for me these films are about striking images and what can be done with a moving camera. They both drag a little in places, but more than make up for it in extended bursts of suspense and action.

Argento demonstrates the power of looking and framing what you see. Both Argento and Taylor create impressive works at pace. Yuzna is enthusiastic and professional, even when he must know the problems with his script. Assonitis is ambitious and knows what sells. Let’s funnel energy from these unlikely role models into the week ahead.

- On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft, Stephen King (2001)

- Tentacles, dir. Ovidio G. Assonitis (1977)

- Amphibious, dir. Brian Yuzna (2010)

- Real Life, Brandon Taylor (2020)

- Four Flies on Grey Velvet, dir. Dario Argento (1971)

- The Cat o’ Nine Tails, dir. Dario Argento (1971)

Slippery surfaces

I started the week with Blade Runner 2049. I was frustrated with it in 2017, but watching it over three nights at home, I’m more forgiving. It’s way too long. It looks beautiful, and it has some fascinating ideas, but the story is broken. The main villain disappears without much comment, and I didn’t buy the replicant rebellion, so the idea of K sacrificing himself had little emotional weight. It’s disappointing. There’s an interview in which Ridley Scott gleefully claims to have been heavily involved with writing the script, which might explain a few things. I did find K’s relationship with his home AI moving. She felt like the heart of the film. It’s a glimpse of what could have been.

(Am I doing weekly summary posts now? Perhaps I am. It helps me notice what impact the week’s books and films have had on me. Hand-written notes just get lost in the stream of ink on paper.)

My Year of Rest and Relaxation, by Ottessa Moshfegh, left me cold too. I admired it — the prose craft is superb, and it had funny moments, but I got bored and ended up skimming the final third. The unnamed protagonist had similarities to Eileen, Moshfegh’s previous novel, which I really enjoyed. This felt more like one of the art projects she satirises. It almost became another one of those books that snarled up my reading rotors in 2020, but I spotted the danger and switched to speed reading mode. I’m high-fiving myself for that.

From there, I jumped into The Man Who Saw Everything, by Deborah Levy, which was a lot more interesting. Her prose is impressive, with a formal air, possibly because she tends to write characters with academic backgrounds. I remember there being a surprising amount of dry economics and politics in Hot Milk, although that it’s been a while since I read that. She manages to make Saul Adler both sympathetic and unpleasant in his perfectly justified narcissism, and the ending felt suitably weighted and emotional. She makes the jumps in time pay off.

I closed the week with three sparky films. In Spontaneous, Brian Druffield somehow managed to make a film about high school students spontaneously exploding be funny, romantic, horrifying, sad and hopeful. There is a definite feel of a school shooting about the randomness of people dying in front of you, but the central relationship is sweet, and Mara is a fantastic comical and complex teenager (a stellar performance from Katherine Langford). It also feels right for COVID times.

The Woman Who Ran couldn’t be more different. In the suburbs of Seoul, Gam-hee visits old friends she hasn’t seen in years because her husband is away. She tells them she is happy, but this is the first time she has left his side since they were married, and we sense mixed feelings under the surface. It’s like she is trying on her friends lives to see if they are a better fit than her own.

Finally, swayed after a glass of wine by the superlatives in the Mubi description, there was All the Vermeers in New York, a weird, awkward independent film from 1990, that mixes a slightly grating jazz soundtrack with shots of New York, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, paintings by Vermeer, conversations between students who somehow share a ginormous flat in Manhattan, an aggressively out-of-place interaction between an artist and a gallery curator, and a stockbroker who has fallen in love with a student half his age. It’s one of those messes I’m glad I experienced, but I can’t recommend.

- Blade Runner 2049, dir. Denis Villeneuve (2017)

- My Year of Rest and Relaxation, Ottessa Moshfegh (2018)

- The Man Who Saw Everything, Deborah Levy (2019)

- Spontaneous, dir. Brian Duffield (2020)

- The Woman Who Ran, dir. Hong Sang-soo (2020)

- All the Vermeers in New York, dir. Jon Jost (1990)

Autumn and The Long Goodbye

In Ali Smith’s Autumn (2016), when discussing a piece of art, Daniel Gluck asks the young Elisabeth, ‘And what did it make you think about?’. I love the openness of that question. Interpreting art is about making connections. There is a passage where Daniel describes to Elisabeth a collage by a long-forgotten artist, and when I ask myself what Autumn makes me think about, my first answer is — a collage.

I had read that this was a contemporaneous novel, written very quickly over the summer of 2016, in the aftermath of the Brexit vote, but reading interviews with Ali Smith, it was more complicated than that. She had partly written another novel, which also made its way into Autumn, so she must have been writing new material into the structure and details of old material. The story jumps back and forth through time, so you are left with a sense of having looked through an artfully assembled non-chronological series of scenes, much like a collage.

This helped me with my work-in-progress, which slowed to a stop over Christmas. I can imagine Ali Smith standing over a canvas, sticking a scene here, a scene there, gleefully assembling pieces she had written out of order into a final draft. I’m envious of the flow state artists get into. Quick decisions. Instinct. Collaging also reminds me of how a jigsaw comes together. Repeating themes.

The Long Goodbye (1973) was released the year I was born. I guess I’m thinking about births and deaths — I heard a vicar on TV describe the circle of life as ‘hatched, matched and dispatched’ — and time passing. It’s a stunning film noir. Elliot Gould is a pathetic, melancholy Philip Marlowe, pushed and pulled around, desperately loyal to his friends. By the end, that loyalty is exposed as his weakness. The climax is surprising and cathartic. The story’s character work pays off. It’s like a novel in the way Marlowe constantly talks to himself, revealing his inner world. No matter what eccentric scene he comes across, he reflexively says, ‘It’s okay with me’. Until finally, it is not okay.

- Autumn, Ali Smith (2016)

- The Long Goodbye, dir. Robert Altman (1973)