Michael Walters

Notes from the peninsula

She Dies Tomorrow (2020)

Director: Amy Seimetz

This isn’t a horror film, though it is marketed as one. The camera is often still as figures move towards us, faces blurred by lights or shadows, and this does create a sense of dread. Much more of the film is observing Amy as she says goodbye to the world, stroking the wooden floor of her new house, and pressing her cheek against its walls. The story jumps through time, allowing us to piece together the events that have led to Amy’s last day. It’s a tactile, sensual film, slow and beautifully acted, but it does invoke anxiety.

It opens with Amy telling her friend Jane that she knows she is going to die the following day. Jane is a fast-talking, anxious person, and is only half-listening to Amy’s words, but they slowly sink in, and when they do Jane begins to believe that she is also going to die the next day. The film becomes a succession of conversations, the idea spreading from person to person, with coloured lights flashing that only they can see, so we don’t know if it is an alien invasion, a virus, a mass delusion, or something else.

It’s affecting, but also mordantly funny in places. Different people react in different ways to their fast approaching death, some doing terrible things, others simply telling each other the truth. The idea of the film lingered in my mind. We’re all going to die. Perhaps even tomorrow.

Director: Kiyoshi Kurosawa

I couldn’t resist another film by my new favourite director, Kiyoshi Kurosawa, care of my Mubi subscription. Knowing a film I fancy is going to disappear in a few days makes me create the time to watch it. It’s an interesting way to beat the paralysis of too much choice. I’d read that Kurosawa was an eclectic director, and this film proves that. Even though there are a couple of scenes that play on Yoko’s fears, it is mostly gentle, amusing and sad.

Atsuko Maeda’s Yoko is a mesmerising presence. She is a reporter for a Japanese travel programme that is making an episode in Uzbekistan. The crew keep their distance from her, making her do ridiculous, unpleasant things, like riding a violently spinning fairground ride over and over again, so they can get the right camera shot, and pressuring her to eat a rice dish from a street vendor even though it is not fully cooked. She is a trooper and does everything she is asked. But once the filming is finished, she goes on mini adventures, getting lost in the streets of whichever town she is in. Her job is unfulfilling, and she feels adrift.

Where Japan is surrounded by water, Uzbekistan is landlocked, and the crew’s translator, Temur, tells Yoko that he is envious of her living near the sea. He sees it as freedom, but for her it is dangerous. She is a fearful person, and Kurosawa makes her everyday experiences in Uzbekistan feel threatening. Slowly she realises her fear causes more trouble than it is worth.

Director: Krzysztof Kieślowski

Tomek is nineteen, lonely and living with his possessive godmother in a Polish apartment block. Every evening he learns languages in his room until Magda, the woman he is spying on through his telescope, comes home from work. She is an artist and seems to be living a colourful life. Tomek thinks he is in love with her, but his attention becomes harassment. One day he realises he has gone too far and tells her what he has been doing. The ensuing confrontations teach them both a lesson about love.

Magda’s well-lit flat is full of paintings, materials and interesting objects. When she brings lovers home, Tomek watches until he can’t bear it anymore. His room is small, a child-sized room for a grown man, and his godmother’s flat is old-fashioned and dark. When he eventually declares his love for Magda, and she discovers how far Tomek has gone in his obsession with her, she tries to teach him that there is no such thing as love, it is simply the sexual impulse. The lesson humiliates him. He seems to want nothing from her and is content just to be near her. His love is both inappropriate and pure, unlike his godmother’s love for him, which is built on a disturbing, smothering selfishness, that keeps him stuck with her.

I remember buying Kieślowski’s Three Colours: Blue on VHS in the mid-nineties and carrying it from flat to flat as I worked my way through every rental property in Swansea. I travelled around Europe with a railcard while at university, and the Three Colours trilogy were released around the same time. They were the first foreign language films that I loved, and amongst the first handful of films that seemed outside my family’s experience, by which I suppose I mean my father’s, and so were mine alone. I was graduating from films like Die Hard and Alien, to Miller’s Crossing and Lone Star. Instead of action, I began to value dialogue, characters, imagery and subtext. I don’t know what I would have made of A Short Film About Love when I was in my early twenties, but I’m glad I discovered it now.

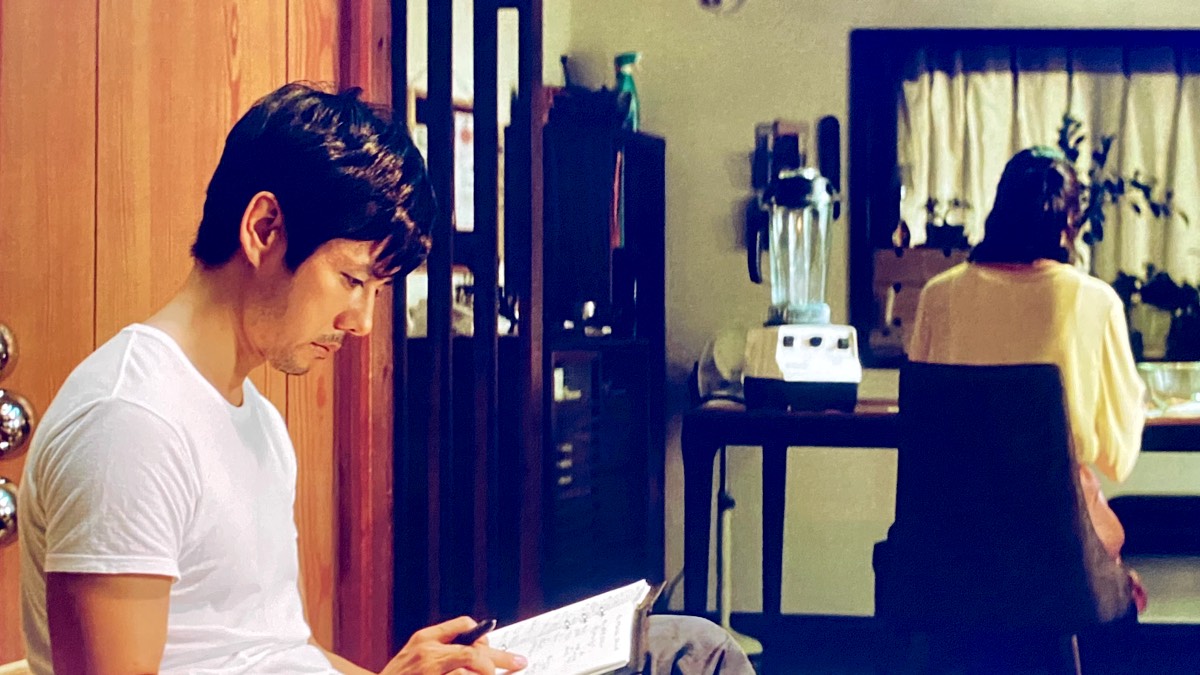

Creepy (2017)

Director: Kiyoshi Kurosawa

The films of Kiyoshi Kurosawa were a revelation to me in October. I started with Pulse (2001), then went back to Cure (1997), and both were masterpieces. Twenty years after Cure, Creepy (2017) is in a similar mould, playing with the framing of scenes to heighten uncanny feelings and making everyday events seem disturbing. Like in Cure, Kurosawa uses the charisma of psychopaths to drive the story, and Masahiro Higashide’s Nogami is a fascinatingly unpleasant creation.

Detective Takakura is a criminal psychologist. After he is wounded by an escaped psychopath, he retires to be a university lecturer, but when an ex-colleague comes to ask him for help on an old case, he is drawn back into police work. Meanwhile, his wife Yasuko is trying to make friends with neighbours after moving into their new home, but the man next door, Nogami, seems to have no social skills and odd ideas about personal boundaries.

The characters are mostly alone and focussed on their individual lives. The source of Nogami’s weird power over people is never explained, which means it’s hard to believe the characters would make some decisions they make, but that’s not to take away from the skill of the filmmaking. I don’t know Japan well enough to know if Kurosawa is making a point about Japanese society, but when there is a predator camouflaged nearby, without a village to shout a warning, people can be picked off, and that applies everywhere.

Creativity 2.0(.21)

I’m in a fallow period, pottering around, looking for the next thing. I started a jigsaw, read a novel, watched the first half of Homecoming (Season 1, with Julia Roberts), listened to podcasts on my walks, and wrote in my notebook. Work was busy, and working from home I find it hard to switch off. I’m easily distracted. The US election sucked a lot of energy out of me. The news is everywhere now. Since finishing #31DaysOfHorror I’ve lost momentum in personal projects. That groove was a powerful source of creative energy.

Finally, though, I’m beginning to feel more centred. Within a couple of weeks, 2021 has gone from being the beginning of the end of things, to the beginning of something new — Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, a COVID-19 vaccine, the end of Dominic Cummings — these are all excellent for my mental health. The world is starting to feel safer.

I now know I can watch a film, make some notes about it, let it simmer in the back of my mind for a few days, then edit it into a decent piece of writing, and I can do that several times a week if necessary. That’s new. I’m not sure what those #31DaysOfHorror blog posts were. They felt like reviews, but I didn’t want to give an opinion on whether films were good, bad, or worth someone’s time. Instead, I tried to find what I liked about each film, then connected it with previous films or my own experiences. I felt obligated to provide a brief synopsis, perhaps because I always had the reader in mind, and they might not have seen the film. I wanted each post to make sense and stand alone.

A handful of people read them. That felt good. The one-film-a-day structure was a potent catalyst for making it a habit, as was posting a link to the post on Twitter. I was pretty wrung out from watching so many films in such a short period. I did love it, but after I’d finished, once I’d let myself decompress, it felt like a massive relief. However, I engaged more deeply with films knowing I had to write about them — that was the power of the challenge, and the public commitment that came with it.

I stopped watching films and writing blog posts completely in November. Drifting creatively is useful, but I’ve learned that without a project, eventually I lose sight of the coastline of my true interests and drift out to sea. I’d like to keep the bits that worked from #31DaysOfHorror, but make it less intense, more sustainable, and more aligned with my current goals.

Posting to my blog every day kept me accountable. That was my measure of progress. Looking back at those thirty-one posts I see what I achieved, and I feel proud of a good creative project. Having a page on my website pulling those posts together makes it feel coherent, just like seeing The Complex and Signal existing in the world does.

My next novel is plodding away in the background. I sit with it for up to an hour every morning. Some days I write a hundred words, occasionally I write none, but on other days I might write as much as five hundred. It’s intermittent and slow-going. Publishing short blog posts and posting them on Twitter — hell, just posting on Twitter and getting a few likes — gives me a feeling of accomplishment, and a dopamine rush writing a novel can’t compete with day to day.

A short story is a month’s work for me, and a novel is years of effort. This novel might never get published and only be read in three years time by one diehard fan willing to read an 80,000-word .docx file. I love you, man, but if the Time Wizard showed me his crystal ball, and that was how it was going to be, I’m not sure if I would go on. The hope of being published and having my work exist on its own terms in the world is a sustaining force. Without that hope, I’d like to think I would still write stories, because it serves some internal purpose, but honestly, I don’t know.

That’s what I’m competing with in my head. I don’t want my writing practice to feel leaden and dull. I’m writing good sentences, even though it is difficult work. Writing The Complex, I had the structure of a creative writing Masters to get a draft finished. Now I’m in the world, a published author, but with no agent, no contract, no support structures, working full-time at home in a completely different field, living through a pandemic, with one child in secondary school and another at a COVID-ridden university, trying to keep some momentum going.

There is transition energy afoot. It’s been a fuck of(f of) a year. I’m starting my annual process of looking back, so I can look forward. I’m lucky in all the ways that matter. Writing is hard — it has always been hard — but it still feels like the most important thing I can do with my spare time. I don’t write for the pleasure of writing, but it means a lot to me, and I manage to create space in my life to do it. For that I am thankful.

Over the next few weeks, as we come to the end of 2020, everything I’ve written about here will shake out. I can’t stay still for long, although I do try. The ideal I hold in my head of a slow, loving, meaningful life always seems just out of reach, but I do my best with what I have.

I wonder what next year will bring? I wonder how I can make my craft feel more fun? With those questions in mind, we enter a season of change.

Doctor Sleep (2019)

Director: Mike Flanagan

Danny Torrance is an alcoholic, but finds a place of peace and sobriety in New Hampshire, where he uses his psychic power, which he calls the shine, to ease the deaths of the elderly people in a local hospice. Death isn’t often realistically shown in films — not the quiet deaths, the elderly deaths, the four a.m. in an empty room, afraid and alone deaths – but in Doctor Sleep, we see final breaths leave peoples bodies. It’s shocking, because it is portrayed so simply and truthfully, but it is also life-affirming. Danny is performing the ultimate service, soothing people out of life, just as a midwife brings a baby into it.

We also see a young boy with the shine horrifically murdered by an extended family of vampire-like people, his death deliberately brutal and painful to maximise the amount of dying breath he releases, which is their food. Over several years, Danny has psychic conversations with Abra, a teenager with an incredibly strong shine who he hasn’t met. She witnesses the boy’s death. Using her power, she tracks Danny down to ask for his help, but he warns her to keep her power under wraps, like he has, because the creatures, who call themselves the True Knot, will come for her next.

Rose the Hat is an interesting villain. Her group acts like a family, with strong bonds and loyalty, and we are sympathetic to their ever-worsening hunger, even knowing they are picking off shine children across America. They are at the top of the food chain, above humans, and need to find people who are potent with the shine for nourishment. As Crow laments, children have the strongest shine, before the adult world drains them, but in the modern world technology dulls even children’s shines. When Rose senses Abra, she resolves to track her down. Danny, Abra and Rose the Hat meet for a final showdown at The Overlook, and that’s a fine finale to my 2020 #31DaysOfHorror.

Director: James Whale

The Bride of Frankenstein contains some of the most iconic images in cinema, but it opens with a scene I really didn’t expect — Lord Byron and Percy Shelley praising Mary Shelley for her book, Frankenstein. In a bold move by the film-makers, Shelley herself continues the story from the end of the 1931 film. Even this is not as bold as the little people in jars, grown by Doctor Septimus Pretorius in his attempts to create a woman, and shown to Henry Frankenstein to get him to help Pretorius’s cause. The mini king, queen, devil, and bishop caper around, providing unexpected surreal slapstick. Like the monster is made of body parts, The Bride of Frankenstein feels like it is made of several films.

Doctor Pretorius is a singularly evil presence. As Pretorius cajoles and blackmails Frankenstein into helping him in his laboratory, the monster wanders the countryside, hungry and lonely. In a famous scene, a blind old man plays the violin, attracting the monster, who is accepted into the man’s home. But the local villagers cannot let the monster alone, and he is eventually caught, but he escapes and meets Pretorius in a nearby crypt.

The final quarter dials up the suspense. The laboratory is familiar from clips played for years on television. It’s amazing to think how thoroughly Bride of Frankenstein has permeated Western popular culture. The score is simply a persistent beat, like the Bride’s heart, and it’s a fantastic touch to have the same actress play both Bride and Mary Shelley. As the Bride opens her eyes, we hear one of the most famous lines in movie history — ‘She’s alive! Alive!’.

Letterboxd: The Bride of Frankenstein (1935), dir. James Whale.

The Exorcist (1973)

Director: William Friedkin

The Exorcist is a cultural behemoth. It’s my twenty-ninth film in this year’s #31DaysOfHorror, and I’m feeling horror fatigue. The film has a weighty reputation — I’d seen clips on television, of Regan vomiting on Father Karras, and turning her head fully around, and I remembered the opening sequence in Iraq, probably from the DVD I bought but never watched to the end. I can’t remember why I didn’t watch it to the end.

It’s an astonishing film and deserves the plaudits. As I watched, the question that kept coming up in my mind was, why Regan? Father Karras asks Father Merrin that question directly, in a scene that is cut from the theatrical release. Merrin replies the point is to make humans despair and believe they are not worthy of God’s love. This is a little disingenuous. At the start of the film, Merrin uncovers relics and objects from an archaeological dig, including an image of the demon, and a catholic medal. He heads back to America, saying there is something he has to do. Later, when Karras plays the recording of Regan’s voices backwards, the demon says, ’Fear the priest. Merrin!’. This is before Father Merrin knows anything about Regan. It implies the demon has been exorcised by Merrin before, and we wonder if Merrin’s digging for relics somehow caused Regan’s possession.

These rabbit holes aside, for me this is Regan’s mother’s film. Ellen Burstyn is magnificent as Chris MacNeil. Some of the most affecting scenes are when we see her rage and fight for her daughter’s life, as well as despair and grieve for what her daughter has become. On a lighter note, when Kinderman, the detective, is trying to get Father Karras to help with his investigation (mainly by being creepy, threatening and odd), there is some high quality tennis happening on the courts behind them. I enjoyed that. That’s the power of a 4K restoration for you.

Tenebre (1982)

Director: Dario Argento

Tenebre is set in Rome, but we could be anywhere, because the story stays in hotel rooms, suburban streets and modernist buildings made of concrete and glass. There are artfully sculpted gardens of stone, water and trees. These locations lend themselves to the roving camera, and Argento likes to play the voyeuristic killer. The most famous scene has the camera drift slowly around the outside of a home, music blaring from a woman’s bedroom, focussing on the roof tiles, the walls, and the window slats, moving from room to room, as the killer takes two victims.

Thriller writer Peter Neal travels to Rome to market his latest book, Tenebrae (which means ‘darkness’), but he arrives to find a serial killer is mimicking in real life the murders in his book. The killer leaves notes under his hotel room door, and Neal gets drawn in to the killer’s game.

Argento knows films are inherently voyeuristic, and is aware of the criticism against him, and while the men die, the women do die in much more elaborate ways. He plays with our expectations, and has a protagonist who takes on the charges of misogyny directly. Giallo films usually have convoluted plots that lose me by the end, but this one makes sense. The set pieces are impressive, the story moves at a pace, the locations are fantastic, and the ending works — this is now one of my favourites.

Land of the Dead (2005)

Director: George A. Romero

I’d been so careful choosing films until last night, and I thought I’d take a chance on this because it’s directed by George Romero. It felt like a safe bet, but I was wrong. This film made me angry. I admire the original trilogy, even if I don’t love them, so I’m surprised at how mindless Land of the Dead is. Romero directs it as an action film, and there is no depth or charm.

In the city of Fiddler’s Green, the moneyed few relax in a tall skyscraper run by Kaufman, played by Dennis Hopper. On the streets below, ordinary people eke out an existence, surviving on supply trips to nearby towns, which are full of zombies who act out zombie versions of their previous lives. Zombie intelligence is evolving, and a zombie garage attendant begins to work some key things out — that fireworks are a deadly distraction, how to fire a gun, and that being dead they can walk across the floor of the river protecting the city.

It’s another take on the conflict between the rich elite and the working classes. The best thing about it is John Leguizamo as Cholo, who at least has a character arc. Asia Argento’s Slack is fun too. But the bar is low, my friends. The bar is low. I’m not sure why I’m so upset. Even bad movies can be fun. I guess I thought I would have some brains to gnaw on, but there were no brains to gnaw on here.

Christine (1983)

Director: John Carpenter

Stephen King is brilliant at weaving vivid teenage experiences into his novels. Christine was one of the formative books of my childhood. The film doesn’t have time to go as deep as the book into the love triangle of Arnie, his best friend Dennis, and new girl Leigh Cabot. This is a horror film first and foremost.

Awkward Arnie and popular high school quarterback Dennis are an odd couple. When Arnie impulsively buys Christine, a dilapidated red-and-white 1957 Plymouth Fury, tension between them mounts, and Arnie’s personality changes. Dennis is the popular one in school, so he is stunned when new girl Leigh chooses the new Arnie over him. But Christine is a jealous and vengeful mistress.

When bully Buddy Repperton gets his gang to trash Christine, and Arnie discovers the wreckage, he realises Christine can fix herself. When he says, ‘Show me’, and stands back to let the car do her thing, it is an intimate, almost sexual act. The car is always more important to him than the girl. The car brings out the worst in Arnie. Like Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, Arnie wrestles with his newfound illicit power. Christine channels his unconscious rage and wreaks havoc. It isn’t love. Possessiveness is a power game.

Prom Night (1980)

Director: Paul Lynch

Like Scream’s Ghostface, the killer in Prom Night can be dodged and knocked over. This is not Michael Myers. There is a lot of disco. Jamie Lee Curtis is a fantastic dancer — this role for her comes straight after Halloween and The Fog, so it’s impossible not to compare it with Carpenter’s work, which is unfair. The students all come across as high school kids, and the performances and locations are realistic, but it looks cheap next to Halloween.

Curtis plays Kimberly Hammond, whose sister, Robin, we see killed six years earlier in a bullies’ game which goes horribly wrong. The group of eleven-year-olds — Wendy, Jude, Kelly and Nick — hide what they did, and a local man gets the blame. On their prom night, of course, the man escapes and returns to the scene of the crime.

There are shades of Carrie when bully group leader Wendy plots to ruin Kimberly’s prom, and much of the opening hour is teen drama, but there are some great moments — Kimberly and Nick in an extended dance sequence under the disco lights, the likeable Slick trying to escape the killer by driving his souped-up van in circles, and the awful Lou’s decapitation. The killer is hyperactive and cartoon-like, especially when wielding an axe, and the fighting near the end is unintentionally hilarious, but it does take an unexpectedly moving turn as the credits roll.

Director: Gore Verbinski

An ambitious young executive, Lockhart, is sent to a Swiss sanitorium to bring back his company’s rogue CEO, Morris Pembroke. The head of the spa, Dr. Heinreich Volmer, drips bad guy charm, but is also the voice of scientific reason. The patients at the spa are semi-retired high-flying executives, seemingly half-mad with wellness rhetoric, convinced they feel healthy, but never healthy enough to leave.

There are elements of Jacob’s Ladder, The Shining, Shutter Island and even Eyes Wide Shut. It’s an adult fairy tale, and Lockhart suffers at every turn. Like the amateur historian who helps him with his questions about the history of the area and is left a desiccated husk, Lockhart is good at puzzles. Before arriving at the spa, Lockhart visits his mother in her down-at-heel retirement home, and she gives him a ceramic ballerina she has painted. She says the ballerinas eyes are closed because she is dreaming. She also tells him he won’t come back from Switzerland. These two thoughts dominate the rest of the film, because once Lockhart starts drinking the water at the spa, we are given the puzzle of working out what is real and what is not.

The vampiric financial services industry, represented by Pembroke and Lockhart, is in conflict with the parasitic wellness industry, but the driver who takes the rich clientele to the spa does his job, like his father did, and that’s enough for him. The rowdy teenagers in the village are poor and can only look up at the wealth on the mountain top. Nobody ever leaves the spa, and as Hannah, the mysterious young woman who drifts around the grounds, says — why would anyone want to?

Letterboxd: A Cure for Wellness (2017), dir. Gore Verbinski.

The Dead Center (2019)

Director: Billy Senese

In a Nashville morgue, an unnamed man comes back to life and escapes. Sheriff Edward Graham investigates the missing body, but across town, psychiatrist Daniel Forrester checks the now unresponsive man into a ward at the psychiatric hospital. These two strands interweave, as the sheriff investigates the man’s background and life, and the psychiatrist tries to get the man to remember who he is.

I didn’t know anything about this going into it. With older films, when I’m jotting my thoughts down like this, I don’t worry too much about spoilers, but with newer films I’m more cagey. The psychiatric hospital is wonderfully realistic. Apparently, consultant psychiatrists helped ensure the routines, types of patients, and medical processes were accurate, and that comes across. Daniel is one of those potentially cliched trouble doctors who break the rules, but Shane Carruth is a good enough actor to make us believe in him.

It does have a hospital drama vibe in places, but this is a short, sharp film, less than ninety minutes long, and it zips along. By the final third we suspect what’s coming. Nothing is over-explained, which along with the smart camerawork, gives the film a nice feeling of dread, and it nails the dismount.

It Follows (2015)

Director: David Robert Mitchell

The film opens with a wide shot of a leafy suburban street, and we look closely for whatever we think the director wants us to see. Like Jay, we are trained from the start to scan the horizon for trouble. Jay is innocent, a virgin, sensitive to nature, noticing insects and leaves on the trees. After sex with Hugh in his car, she talks about what might be different now, while studying the flowers growing through the concrete. Seconds later, Hugh has chloroformed her, and her childhood is suddenly over. After showing her the thing that will now come after her, he dumps her half-naked in the street and drives off.

This is a deeply sad film. It’s an allegory for rape, and the emotional aftermath for the victim. At the cinema, Jay and Hugh play the ‘who would you swap places with’ game, but Hugh is trying to swap places with Jay, so it is revealing he chooses the little boy, because he doesn’t know yet about death. Hugh infects Jay with a sexually-transmitted curse in the shape of an endlessly approaching zombie. Jay’s sister, Kelly, and Kelly’s friends, Paul and Yara, try to help. All the young people, including the older, promiscuous Greg, are sweet and kind to each other. We never see Jay’s mother’s face, and her father only shows up as one of the thing’s many violent forms. The adults cannot help her.

Hugh’s assault traumatises Jay, and not only is she not sure what happened, nobody believes her account at first either. Jay finds herself in a different, frightening, more serious world. In a series of skillfully constructed set pieces, we follow Jay’s journey, from innocence, through trauma and support, to some kind of resolution. Passing the curse on buys you time, but doesn’t break the chain. Hugh has condemned her to a life of anxiety (isn’t that the definition of PTSD?) and now she can never know how far death is behind her.

The Beyond (1980)

Director: Lucio Fulci

Returning to Fulciland, The Beyond is more coherent than City of the Living Dead, but of course, it’s still driven by images. Like The Amityville Horror, there is a portal to hell in the basement, and people get mysteriously hurt while working in the house. Like Hellraiser a few years later, the dead return to claim the ones that escape from hell. It’s a film full of ideas, not all of which make narrative sense.

Liza Merrill inherits from her mother the wreck of the Seven Doors Hotel, Louisiana, and plans to renovate it. She doesn’t know that fifty-odd years earlier, a lynch-mob killed an artist, Schweick, who left a painting unfinished in his room. His death was an accidental sacrifice that partially opened one of the seven portals of hell, and her work on the house fully opens it, giving Schweick the chance to return. In her attempts to work out what is going on, she teams up with Dr John McCabe from the local hospital.

There is a lot going on — a blind woman sent from hell with a message, a man eaten alive by tarantulas, maps that change as characters look at them, a doctor who wants to measure the brain waves of corpses — it’s violent and gruesome and icky. You are not given much opportunity to care about the characters. Towards the end, Liza and John get caught in a space-time loop that leads them inexorably to the bleakest ending to a film that I can remember.

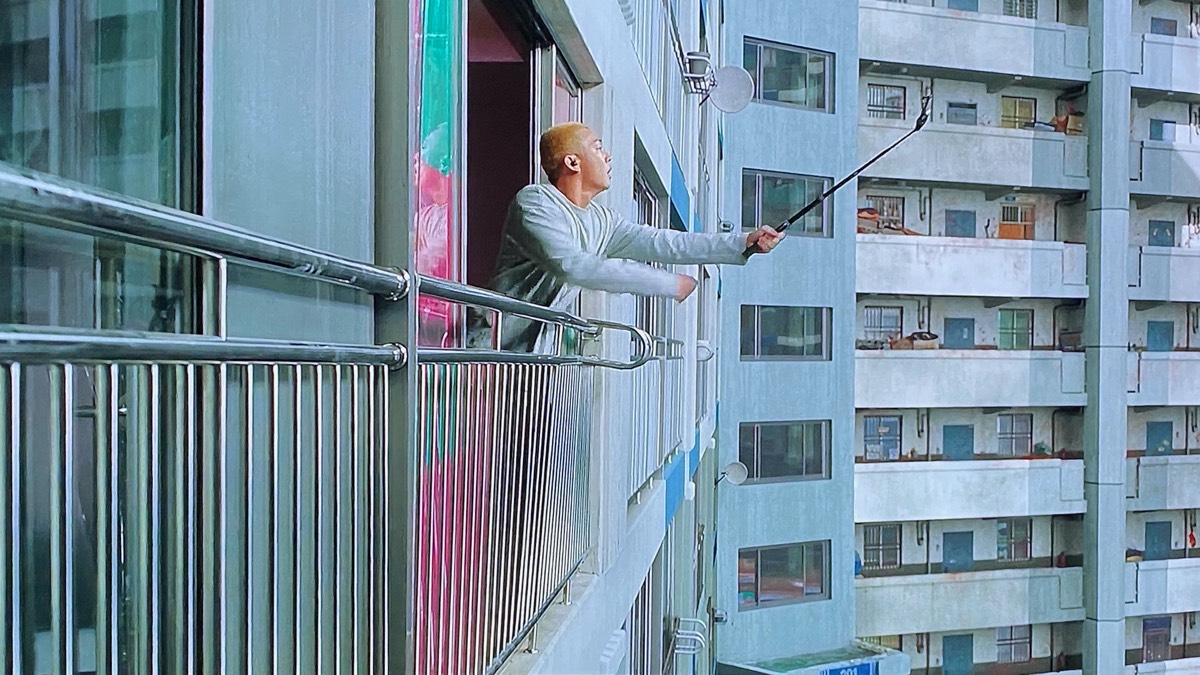

#Alive (2020)

Director: Cho Il-hyung

After Fulci’s barely moving undead, the running zombies of #Alive are a bit of a shock. Technology is an ally here, which is refreshing in a horror film, although at the start, Joon-woo seems to be in a semi-infantile state, still living with his parents, and spending most of his spare time playing video games. He lives on the third floor of an eight-storey apartment complex in Seoul. When a zombie virus hits his part of the city, his parents are out, and he barricades himself in the apartment. Alone, he resolves to survive, but having chosen to play his video game over buying food as his mother asked, he has no supplies.

It reminded me strongly of the French film, The Night Eats the World, which has a man holed up alone in a swanky Parisian apartment block after a zombie virus. There are several parallels with it, from how the zombies behave, to survival methods, to the arrival of another person at the mid-point. The apartment block corridors are effectively awful spaces for zombie chases. #Alive brings the extra ingredient of technology into the mix. While he has no mobile signal or internet connection, he can still pilot a drone, and it is the message he posts on social media just before the connections go down that gives him his best chance of survival.

The relationship he strikes up with Yoo-bin, who is holed up in the apartment opposite him, is sweet, and she is the brains in their partnership. It’s a coming-of-age story underneath the standard zombie story tropes. It doesn’t shy away from the desperation and despair Joon-woo experiences, but at heart it’s an action-romance for teenagers, and no worse for that.

The Mummy (1932)

Director: Karl Freund

The original Universal horror films are a bit of a blind spot for me. They weren’t on TV in our house, so I have no childhood affinity to them, and once my parents let me watch horror, I was straight into Jaws, The Car, Duel, Piranha — pacy, garish, seventies films. I didn’t go back beyond my father’s earliest favourites, which were films like Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Night of the Hunter, and Psycho.

Two years ago, I made an effort to watch Tod Browning’s Dracula and James Whale’s Frankenstein, but they were more like homework than a pleasure. However, that did mean that as soon as I heard Edward Van Sloan’s voice I saw in his Dr Muller both Van Helsing and Dr Waldman. In The Mummy, it is his belief in Egyptian magic and knowledge of ancient Egypt that keeps the colonial English heroes in the game.

Imhotep has many magical powers, including mind control. Boris Karloff’s stare is a thing to behold. Imhotep tricks the British archaeologists into digging up the tomb of his great love, the princess Anck-su-namun, and ensuring that her remains are displayed in Cairo, not London. The air of arrogant British colonialism is thick, but in this, Imhotep outsmarts the archaeologists, who it seems will do anything in the name of science. Then he goes after Helen Grosvenor, a half-Egyptian British woman in Cairo, who he believes is his love reincarnated.

I suspect with practice, or guidance, I could get more out of films from this period. I’m glad I watched it, but it’s still more like homework.

Director: Lucio Fulci

Zombies really bothered me as a kid. Seeing the insides of the human body spill out was as pure a vision of horror as I could imagine. Guts should not be outside of your body, full stop. I only watched one zombie film, whose title I can’t remember, and the ten minutes I managed of it fucked me up for weeks.

In Dunwich, Massachusetts, a priest, Father Thomas, throws a noose over a tree in a graveyard and hangs himself. This somehow opens the gates of hell. In New York, Mary has a vision of the dead priest at a seance, and collapses as if dead, only to wake up half-buried in her coffin. She is saved by Peter, a reporter, and their investigations lead them to Dunwich, where the dead priest is killing its citizens in grisly ways.

Fulci thrives on disgust and revulsion, but things take their time to get going. Characters talk directly to the camera. Bodies come and go. A dead woman moves around an artists’ house. There are close up shots of eyes. Waves of maggots. Bleeding walls. A jealous father drills the head of a boy he finds with his daughter. The images sneak up on you, then smack you in the face.

Dunwich looks suitably pre-apocalyptic, with mist, strong winds, and empty streets. Much of the population are so pale and odd, they could already by dead. The soundtrack, sound effects and suburban streets reminded me of Michael Jackson’s Thriller — it had to have been an influence. In this strange place, the dynamic of Gerry and Sandra is interesting — he is a therapist who lets his wife wander into his sessions, and Sandra is his patient who he feels free to visit in the middle of the night when she’s frightened. She is an artist and paints strange horned creatures, and monster eyes. He has odd pictures on his office wall too, possibly her work. Does he have any other patients?!

As abject as these films might seem on scuzzy VHS cassettes and tiny television screens, they are never as bad when you go back to them. Fulci sacrifices character development and story for the power of the image. By the end I felt wrung out. Nihilism is exhausting.

Letterboxd: City of the Living Dead (1980), dir. Lucio Fulci.

Blade (1998)

Director: Stephen Norrington

The opening sequence is brilliant. A woman lures a man to a party in an abattoir. It’s an aggressive crowd, and when the fire sprinklers come on, it’s not water but blood, and everyone around the man turns into a vampire. Blade arrives to kill as many vampires as he can — his raison d‘etre. It’s thrilling and weird. Vampires now own half of Manhattan. There is a vampire Bible, and a ritual to awaken a blood god. Which makes sense, right? Vampires would worship a blood god.

Blade is like a magical source of future movie ideas. The long black jacket and sunglasses, kung-fu fight sequences, being ‘the chosen one’, and even the black marble hallway fight scene can all be found in The Matrix twelve months later. The flow of blood through an elaborate ancient mechanism to bring an apocalypse appears in The Cabin in the Woods. And while Blade came first, his samurai-like lifestyle, especially the meditation joss sticks and little cushion, whilst laudible, is nowhere near as cool as Forest Whittaker in his pigeon loft in Ghost Dog. Just sayin’.

Blade is also the first of Marvel’s adult superhero films, and we are still seeing that thread unfurl. Wesley Snipes even tried to get a version of Black Panther made before he signed up for Blade. It’s a fun, if empty, blockbuster, with an amazing performance by Stephen Dorff as the baddest of the bad vampires, Deacon Frost. Blade is a hidden cultural phenomenon.