Michael Walters

Notes from the peninsula

Welcome!

This is my little word garden on the internet—Michael Walters, author (it’s true!). I have a speculative fiction novel, THE COMPLEX, out with Salt Publishing, and I’m deep in the writing of a follow-up. I would love it if you gave it a try.

I use Bluesky to connect with people, Letterboxd to track films, and StoryGraph to track books. Follow me and say hello in all those places.

And if you want more of my thoughts on writing in particular, you can subscribe to my posts on PATREON. There’s a Weird and Wonderful tier if you want to support me with a donation, and that now includes notes on the novels I’m reading, but I post regularly to all patrons.

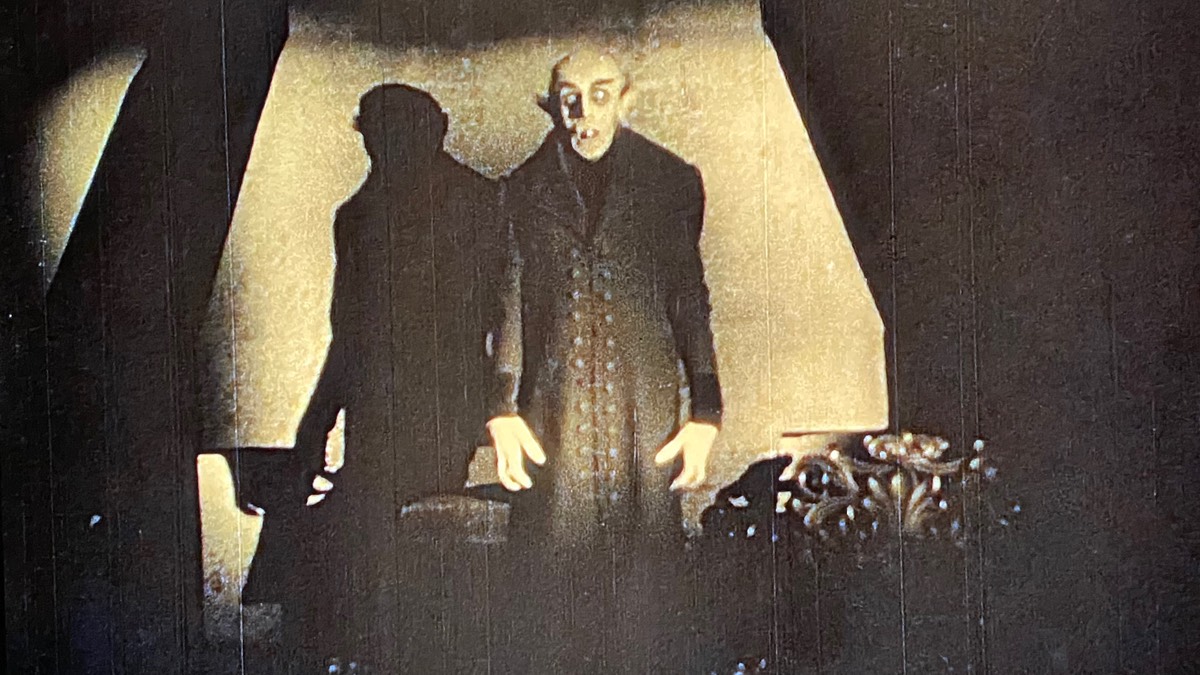

Nosferatu (1922)

Director: F.W. Murnau

I wanted to see the original Master, so I put on the oldest unseen film in my collection, Nosferatu. I appreciated the original Dracula and Frankenstein, but they were pretty dry in places. Nosferatu is ten years older again, and while I’d love to be able to say I love these old classics, this did feel like homework.

Hutter, an estate agent in Wisborg, is sent by his boss, Knock, to Transylvania to sell a dilapidated old building to Count Orlok, a new client. Once there, he is bitten by the Count, who is actually a vampire. Orlok sees a photograph of Hutter’s wife, locks Hutter in his room and sets off for Wisborg. After slaughtering the crew of the ship he is travelling on, Orlok sets about drinking the blood of all the citizens of Wisborg. Hutter rushes home, but his wife, Ellen, realises that only she can put a stop to Orlok’s deadly reign.

There are well-known iconic images and scenes in this film, and it’s amazing to see them in their proper place, for example Orlok rising from his coffin and stalking the ship he is travelling on, the shadow of Orlok on the wall of the stairs as he climbs to Ellen’s bedroom, and Orlok’s disintegration when he is caught in the sun. Max Schreck’s Count Orlok creates electricity in every scene he appears, but the crazed acting of the time stripped away all the tension for me, and there are too many long stretches of travelling between locations, whether by foot or carriage. Having said that, the string of coffins being carried along the main street of Wisborg is shocking. The townsfolk think it’s a plague. That’s when it hit me how deadly this creature is: The Master.

Salem’s Lot (1979)

Director: Tobe Hooper

Salem’s Lot has a special place in my heart. It was the first scary book I ever read. The film is the two part miniseries I remember from the eighties stitched together. It smartly does away with the vast array of characters in the novel and concentrates on Ben Mears, the returning writer, who is researching a book about the Marsten House, which has recently been bought by the public-facing Mr Straker and reclusive Mr Barlow. Straker and Barlow have also just bought an antique shop in the town, and the local people are fascinated by the mysterious pair. Of course, Mr Barlow is a vampire, and very quickly he begins to turn the townsfolk into his slave vampires. Ben and his companions have to stop him.

I can’t remember the last three-hour film I watched, but there was enough going on in this one to keep my interest. The script is good. There’s a believable (if slightly cringey) romance between Ben and Susan, a new teacher at his old high school. The vampires look properly dead and are very scary, and the little dramas and jealousies of small town life are believable. I’d forgotten the iconic moments, like the younger boy floating outside his older brother’s window, and the grave digger opening the coffin. It all still works.

It was fun to see how Tobe Hooper’s Marsten House had echoes of his Texas Chain Saw Massacre house, with feathers and dust on the floor, the stuffed animals on the walls, and general air of rot and decay. It was a little upsetting to realise how closely The Master in Jakob’s Wife mirrored Barlow. I mean, come on! I guess it shows the power of Barlow’s screen presence, and ultimately even he is a homage to Nosferatu.

Nightmare Beach (1989)

Director: Umberto Lenzi, Harry Kirkpatrick

It’s the late eighties, and it’s Spring break, somewhere near Miami, Florida. Thousands of young people are in bars and cars all along the seafront, drinking, sunbathing and having sex. A biker gang has a vendetta against local police chief Strycher after he framed their leader, Diablo, who we see die in the electric chair. But within days a mysterious biker with a devil’s trident on the back of his motorcycle starts electrocuting random people, and the Mayor, who is desperate to keep the murders under wraps, begins to wonder if Diablo is back from the dead.

Nightmare Beach shouldn’t work. It’s cheesy and sleazy, the acting is ropey, the dialogue is so-so, and the premise is ridiculous. The Lighthouse, my original pick, was boring me silly, so I flicked through my watchlist and picked Nightmare Beach instead because it seemed like the complete opposite. It was only on my watchlist at all because of its link to director Umberto Lenzi, who made the bonkers-wonderful Nightmare City.

But there is a lot to love in Nightmare Beach. It’s made well, with solid cinematography and an all-out eighties rock-style soundtrack, and the central pairing of Skip and Gail are surprisingly sweet and well played. The redoubtable John Saxon plays the villainous local police chief, and the special effects of the various kills are pretty good. It’s fun! I would have been fifteen when this was made, and even if I was American, I would never have gone on Spring break like these characters do, so there is some nostalgic wish-fulfillment going on in me, for sure. Everyone is so young and beautiful. An unexpectedly solid slasher that made me feel like a teenager again.

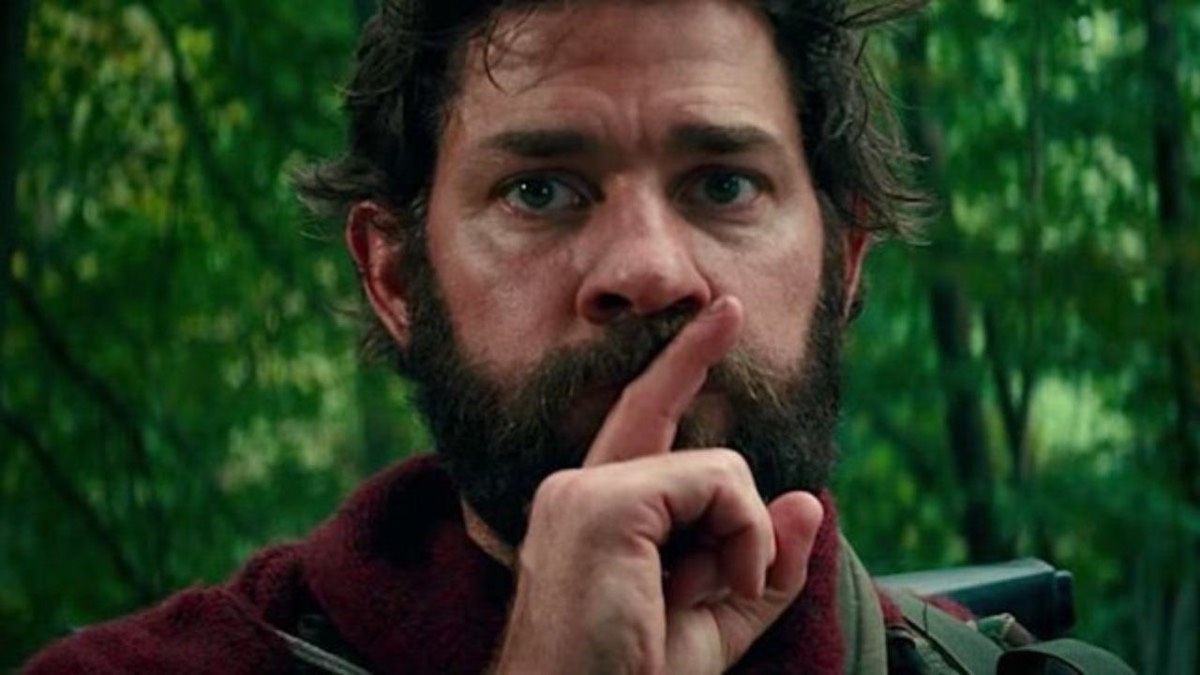

A Quiet Place (2018)

Director: John Krasinski

My brain combined The Thing and The War of the Worlds to suggest to me A Quiet Place, one of many recent horror blockbusters I hadn’t seen. A family are trapped in their valley by blind alien creatures with impenetrable armour and incredibly acute hearing. The family have adapted to the new reality in ingenious way, but their youngest son finds a toy in an abandoned shop, and not old enough to understand the danger, turns it on. The noise it makes attracts an alien that kills him. The film skips ahead a year to show the family struggling with loss and guilt, the trauma of their son’s death compounded by the fact they are fighting to survive off the land, the woman is pregnant, and the smallest noise could get them all killed.

The locations are The Thing-like in spirit but transplanted from Antarctica to rural American cornfields—characters walk between buildings on unspoken errands, there are marked paths lit in the darkness, and an unseen enemy lurks all around. The valley their piece of land lies in makes their farm a visual hub for surrounding farms, whose people they almost never see because it is too dangerous. Everyone has retreated into their homes to survive. (This came out in 2018. How little they knew.) Each night the father lights a fire on top of a corn silo, and the other farms respond with their own. This is all the community they have left.

There are plenty of thoughtful details like this, and Krasinski displays a touch of Spielberg in the way he shows the children’s lives, as well as in the adrenaline-inducing set pieces, some of which remind me of the children running from velociraptors in Jurassic Park. The emotional manipulation can feel a little overt, and the jump scares a bit annoying, but it’s a straight story with children in peril and parental sacrifice at its heart. It’s also great to see a deaf character in such a prominent role in a story. A Quiet Place was a surprise. I can see why it made the splash it did when it came out.

Director: Byron Haskin

I recently watched the Spielberg/Cruise War of the Worlds, which I found surprisingly bleak, so I thought I’d go back to the original 1953 adaptation, The War of the Worlds, to see what that was like. That was also bleak, but softened by the folksy charm of small town 1950s America. It opens with a black and white newsreel montage of both World Wars, then bursts into colour, which I didn’t expect. A meteor comes out of the sky and crashes near the small town of Linda Rosa, where Dr Clayton Forrester is fishing with two scientist friends. The townsfolk are excited, and Forrester gets drawn into investigating the fallen object, while also falling for librarian Sylvia van Buren. More objects arrive, and when alien machines rise out of the burning rock, the army are called in, but they are helpless when the machines attack. Forrester tries to find a weakness in the alien technology, but with the invasion taking place worldwide, a swift, methodical genocide of humankind begins.

It was shocking to see that the more effective scenes in Spielberg’s version were directly lifted from the original, none more obviously than the section where the alien tentacles are investigating the house. This isn’t long after World War 2, but where The Thing From Another World is afraid of communism, this seems to be more about processing the trauma of war. The story lingers in long sections where Forrester moves through a devastated landscape filled with refugees, violent looters and unexpected alien attacks. Every attempt to stop the invasion fails, and humans only survive through perseverance and luck. Ironically in today’s world, it’s the environment that saves them.

The Thing (1982)

Director: John Carpenter

I’m breaking one of my #31DaysofHorror rules with The Thing, because I saw it almost exactly five years ago. It was a key film in getting me into horror movies again after a fifteen year hiatus. The chance to watch it back to back with The Thing From Another World, one of John Carpenter’s favourite films as a child, was too great an opportunity to miss. It’s a different take on the premise of an alien being uncovered in polar ice. In this one, the shape-shifting alien picks off the crew when they are alone, creating exact replicas, so nobody knows who is human and who is not. Suspicion turns to paranoia, and the remaining humans have to make sure the alien doesn’t leave the base and take over the world.

This is one of those films from the eighties that blew my teenage mind. The creature special effects still look spectacular forty years on, and they were created almost entirely by the shockingly young Rob Bottin, who was only twenty years old. The gloopy carnage in 4K HDR made me giggle with shocked joy, but it’s so much more than the special effects. It’s paced beautifully, every scene is tuned to perfection, every character has a personality, and it has one of the most fascinating and entertaining monsters ever put on screen. It shares ideas with the similarly spectacular 1978 Invasion of the Body Snatchers. It’s also, pleasingly, a whodunnit like Werewolves Within.

The Thing is John Carpenter’s best work. There are lots of little call backs to The Thing From Another World, from the title reveal, to the video of the Norwegians standing in a circle, the alien diving on fire out of a window into a bank of snow, the block of ice at the Norwegian base, the wooden slats on the corridor floors, and even the fact MacReady and Captain Hendry are both pilots. Carpenter’s version is an absolute classic and one of my favourite films, full stop.

Director: Christian Nyby

After Shadow in the Cloud, I wanted a calmer, less frenetic experience, but to also feel like the next film flowed from it naturally, so I chose The Thing From Another World. It’s set not long after the end of the second World War and again involves the military. Captain Hendry is a pilot with the US Air Force and is sent with his crew to a remote scientific outpost in the Arctic to investigate a report of a crashed aircraft. The lead scientist is the prickly Dr Carrington, and when the investigative team realise they have discovered the remains of a flying saucer, as well as a frozen alien life form, there is a clash between the military, the scientists and the press as to what they should do next. When the alien is accidentally thawed, its unique biology threatens humanity.

The US military is presented as confident and possibly a little complacent. The soldiers are charming and banter with each other at card tables, while Hendry’s crew tease him about a girl he knows at the outpost they are to be sent to. The newspaper reporter, Ned Scott, seems to have access to all areas, even on a military base, because he’s one of the guys. The tone is closer to comedy than sci-fi or horror. In a weirdly charming scene, scientific assistant Nikki (we only get her first name, presumably as she’s a woman) ties Hendry to a chair because of his predilection when drunk of having ‘octopus hands’ and feeds him whiskey. At this point I wondered what I’d signed up for.

The story gets juicier when the body of the frozen alien creature, a rip-off of Frankenstein’s monster, is accidentally covered with an electric blanket, and after a few hours of unnoticed dripping is set free to begin its killing spree. The lead scientist is a coldly ambitious loon, but he works out that the creature uses blood to regenerate and spread. Of course, the military saves the day, and the reporter gets the final, iconic lines, broadcasting his report: ‘Tell the world. Tell this to everybody, wherever they are. Watch the skies everywhere. Keep looking. Keep watching the skies.’

Director: Roseanne Liang

Horror stretches across many genres, and you can’t always know in advance how horror-y a film is, so with Shadow in the Cloud we are in war-action-horror territory, in that order. Maude Garrett arrives at an about-to-takeoff B-17 in 1943, presenting papers to the crew that let her and her top secret cargo onboard. The men are abusive and dismiss her to the gunner’s position beneath the plane, separating her from her mysterious bag. When Japanese fighters attack, and a creature clinging to the outside of the plane starts pulling it apart, Maude has to escape and somehow get herself and her precious cargo to safety.

Okay, there’s no escaping it—the first half is an unpleasant exercise in controlled misogyny, with our lead Maude stuck in an enclosed space having to listen to the crew on the radio say horrible and disturbing things about her. It goes on way longer than it needs to, and while you could argue it’s necessary for the emotional release of the film’s second half, and conditions were undoubtedly much worse in the nineteen-forties for women in the military, it almost made me turn it off. Chloë Grace Moretz is given plenty of emotional range to work with and was charismatic enough to keep me onboard, and the reward is a halfway handbrake turn where Maude becomes an Indiana Jones-type character in a swashbuckling adventure.

The horror is primarily in the gremlin ripping the plane to pieces mid-flight, but is also in the gross misogyny of the male characters. It scrapes into #31DaysofHorror, but it’s at the outer limits. A mixed experience.

Director: Mario Bava

Lisa and the Devil lives in one of the lesser-known corners of the Mario Bava-verse. Telly Savalas as the possible devil Leandro is an amusing presence, and if he is not particularly devilish, the dream-like plot definitely is. Lost tourist Lisa comes across Leandro in an unnamed European town, and she is immediately afraid of him—he looks like the devil she‘s just seen in a fresco on a church wall. That devil carried the bodies of the dead under his arms, and Leandro is picking up a dummy he’s having repaired to carry home. She tries to return to her group, but the streets become maze-like and darkness falls, so she is forced to ask for a lift with a rich couple and their chauffeur. The car breaks down at the door to a gothic manor house, and when they knock for help, it is answered by Leandro, who invites them inside.

And it just gets more complicated from there. There’s a family, and mannequins, and ghostly knockings, and a dream lover that Lisa thinks she knows, and a killer in the house, and lots of running through enormous abandoned rooms. It all looks ravishing and has plenty of fun performances, but it’s more of a ghostly mystery than particularly frightening, an adult fairy tale. The acting has a hammy, knowing quality which, along with the fantastical tone, constantly reminds the viewer that this is an artifice. I would have enjoyed it more if it had ended on the penultimate scene, but Bava insists on a silly final twist that slightly spoils it.

The Addiction (1995)

Director: Abel Ferrara

After two quite light films, Abel Ferrara’s The Addiction is a hard turn downwards into the circles of hell. Kathleen is studying for a doctorate in philosophy in a grungy, black-and-white New York, where the streets are lined with hustlers and junkies. She is disillusioned with academia, obsessing over the horrors of German and American war atrocities, but unsure what to do about it. One night she is pulled into an alley and bitten by Casanova, a female vampire, who mocks her for not putting up more of a fight. As she slowly transforms into a vampire herself, her contempt for humanity grows, her appetite for human blood increases, and she develops a more practical and horrific philosophy to exist by.

This is a film thick with social commentary, philosophy texts and existential ideas. The first images we see are piles of dead bodies from the Holocaust and Vietnam, and a class of students watching on a projector screen. For Kathleen’s friend Jean, it’s all academic—she is able to eat her sandwich while reading textbooks on the subject—but Kathleen feels the violence on a deeper level. She hates that American politicians look for scapegoats so justice can be seen to be done and the country can move on. Most people want to forget about it. The collective guilt is unbearable, so it is repressed, and the source of the violence remains seeded beneath the surface. The vampires haunting New York talk about evil and sin, but they are also the violent shadow of the collective unconscious.

The final feast, where the newly-graduated Kathleen eats her professors, must have influenced the opening of Blade, where the innocent party-goers are really food. Ferrara would probably say nobody is innocent, and that most of us are, in Casanova’s words, collaborators. Vampires and nihilism go hand in hand, and addiction is can lead to self-destruction, but perhaps there are ways to better harness our human appetites for violence. Ferrara is asking us to do something about it.