Michael Walters

Notes from the peninsula

Welcome!

This is my little word garden on the internet—Michael Walters, author (it’s true!). I have a speculative fiction novel, THE COMPLEX, out with Salt Publishing, and I’m deep in the writing of a follow-up. I would love it if you gave it a try.

I use Bluesky to connect with people, Letterboxd to track films, and StoryGraph to track books. Follow me and say hello in all those places.

And if you want more of my thoughts on writing in particular, you can subscribe to my posts on PATREON. There’s a Weird and Wonderful tier if you want to support me with a donation, and that now includes notes on the novels I’m reading, but I post regularly to all patrons.

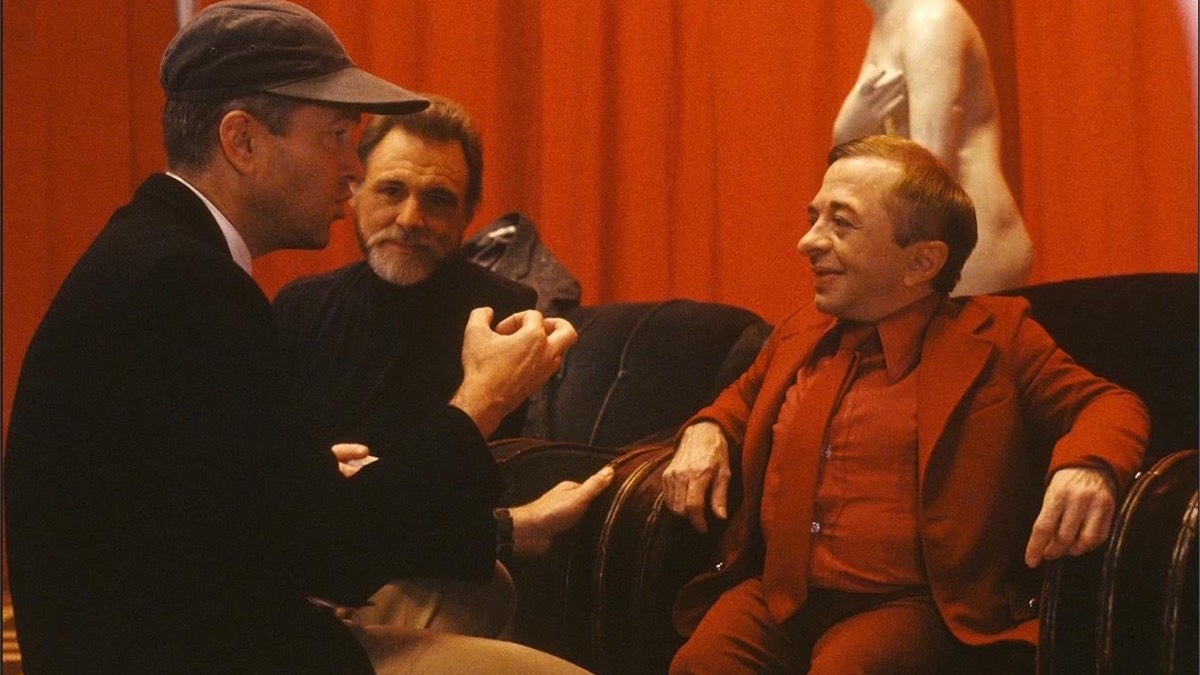

Director: David Lynch

Release year: 1992

A howl of pain from Laura Palmer, the murdered girl that opened the TV series, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me is difficult, heavy, hard to watch in places, and grapples with incest, rape, drug-taking, murder, domestic abuse, and the psychological consequences. Perhaps we get the opening half hour with the citizens of nearby Deer Meadow to connect us with the humour and quirkiness of the TV series, although these people have an obnoxious streak, but it does feel odd, like a different film. By the end, it feels like another universe.

The film is brutal and haunting, but I found it frustrating that Lynch felt compelled to make it at all. It tries to explain and wrap up the mysteries of the TV series, but it doesn’t quite stand on its own as a piece of art. If I hadn’t seen the first season of the TV series, and know the ending of the second, I don’t know how much of this would have made any sense.

Having said all of that, as a telling of the story of a victim of incest, it’s mature, emotionally smart and absolutely devastating. I just wish that either there were less decorative aspects of the TV series, or they were woven in more coherently. However, there are shots and scenes in this film that I will never forget. It’s a flawed masterpiece.

Wild at Heart

Director: David Lynch

Release year: 1990

After Blue Velvet, Lynch made the first season of Twin Peaks, then pivoted into Wild at Heart. It’s a series of deliberately melodramatic, hyper-violent and sexual scenes stitched together into a road movie, with a tenuously-made connection to the Wizard of Oz.

The performances are amazing, but I found the overall effect rather numbing. I didn’t really care about Sailor and Lula’s relationship – in fact, I wanted Lula to strike out on her own, Sailor being mostly a liability. Lula uses Sailor’s violence to escape the clutches of her shockingly possessive mother, who sets off a pack of creatively grim villains to kill Sailor and bring Lula back home. The most interesting part of the film is the middle section, where the sexually ravenous couple begin to open up to each other, and the bad omens mount, including a haunting scene where a woman is wandering near a car crash, not knowing she is dying, looking for her things in the sand.

Lynch said he wanted to make ‘a really modern romance in a violent world – a picture about finding love in Hell’, and I think he succeeded. For me, the ironic tone and melodrama took me too far out of the film, and I found myself sometimes bored, which I hesitate to say about a film with such an enviable reputation. I also have to remind myself that there was nothing like this at the time, and Wild at Heart’s influence can be seen in Reservoir Dogs, True Romance and Pulp Fiction.

Wild at Heart takes Lynch in a different direction. I didn’t love it, but it’s an important stepping stone. Everyone in the film seems to be having fun, and it’s a perfect palette cleanser after the double hit of slow-paced small town darkness in Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks. This is David Lynch on the road and cutting loose.

Blue Velvet

Director: David Lynch

Release year: 1986

I was nervous going in to Blue Velvet, more so than any horror film. It has a fearsome reputation but is also culturally beloved. Dennis Hopper’s over-the-top performance has become iconic, and its themes foreshadow those in the massively popular Twin Peaks. Some films become intimidating over time as more and more is written about them, but it was what I knew of Hopper’s Frank Booth and the sexual violence that put me off watching it for so long.

Blue Velvet is a brilliant film, as outrageous and disturbing as I’d heard, and about many things – innocence, curiosity, darkness, tenderness, violence, growing up. Jeffrey comes home from college because his father has had a stroke. He finds a severed ear on waste ground and takes it to the police. Detective Williams tells Jeffrey not to ask any more questions, but Jeffrey’s curiosity sends him on an odyssey into the underbelly of his seemingly picture book hometown.

Lynch knows his unconscious onions. With Jeffrey’s real father out of action, Detective Williams is a kindly replacement, just as Frank Booth is a sadistic one. The film is full of opposites like this. Jeffrey falls in love with Williams’s daughter, Sandy, but is sexually attracted to the damaged and dangerously masochistic Dorothy, who Frank is blackmailing into sexual slavery. Jeffrey has several opportunities to withdraw from the mystery, but he keeps going, thrilled by the hunt and illicit sex. He wants Sandy and Dorothy, but reality hits when Frank forces him into a hellish drive out of town, where at one point, Frank says to Jeffrey, ‘You are like me.’ Through the film, Jeffrey absorbs some of Frank’s cruelty, hitting Dorothy during sex, and eventually shooting Frank in the head. From a Jungian perspective, by the end Jeffrey has endured a great deal of suffering, but is rewarded with the integration of a large chunk of his own shadow.

Jeffrey’s whole adventure could also be read as a distraction from the grief and fear that his father might die. At one point the camera goes into the severed ear, and at the end it pulls back out of it. Was everything in between a dream?

There’s a fascinating episode on curiosity, by the This Jungian Life podcast, describing curiosity as an innate human drive that can be both useful and destructive. Jeffrey’s voyeurism and passion for the mystery makes him take enormous risks, and by the end he has used what he has learned from Frank and Dorothy to clean up the darkness in the town and create for himself a place of relative contentment. He wrestles with his own violent, sadistic and masochistic impulses, and comes to appreciate how the robins of love from Sandy’s dream also eat fat bugs. Love and darkness are intimate. As Sandy says, ‘It’s a strange world, isn’t it?’

From a writing process perspective, I love how it was conceived by Lynch years earlier as a vague feeling, and a title, to which he later added the image of an ear in a field, and the song Blue Velvet. He considered the screenplay he wrote from those seeds unpleasant and not good enough to make, but after directing Dune, he came back to it. He added a voyeur discovering a murder mystery, and the scene where Dorothy emerges beaten and naked on the street was something he actually experienced as a child.

In Blue Velvet, Lynch successfully created something culturally important and resonant that was also deeply personal. He used his curiosity about his own inner world to create a vivid and vibrant piece of art. That’s inspiring.

Dune

Director: David Lynch

Release year: 1984

I went into Dune thinking I would see something the critics were missing – I mean, how could the director of Eraserhead and The Elephant Man direct a complete dud? – and… it’s so over-the-top, it manages to not be awful.

The Lynch love of dream sequences, moons, and faces in the sky is all here, and it has Eraserhead’s queasy body horror in the villainous Baron Harkonnen, who is so deliberately diseased, vile and pantomime camp, I can’t decide if he is the worst or best part of the film. Sting does inject some actual menace, but then he appears comically greased and almost naked in a winged cod piece, to his father the Baron’s perverse delight, and spoils it.

Having said that, there is plenty to enjoy in the baroque and sometimes surreal visuals, and a few performances are excellent, especially Max von Sydow as Doctor Kynes, the Fremen liason, and Francesca Annis as Lady Jessica. But the plot is a real mess, and the final half hour is painful.

Lynch wrote seven drafts of the screenplay, his final three-hour cut from the final draft was slashed to two hours at the insistence of producer Dino De Laurentiis, and scenes had to be reshot to make sense of it all. He still declines to talk about the film in interviews. The film bombed, and when Lynch in later life talked about the importance of keeping control of the final cut, he must surely be referring to his time with Dune.

The Elephant Man

Director: David Lynch

Release year: 1980

The Elephant Man is as traditional and straightforward as Eraserhead is surreal and obtuse. Both are black and white, and Lynch does use some dream imagery in The Elephant Man, but they’re at opposite end of the narrative spectrum. When you finish The Elephant Man, you are in no doubt about what you’ve just watched and what it means.

The camerawork is precise and every shot is pristine and artful. The story is emotional and mature, with an important message, and the ending is majestic. I appreciated it, and I felt it deeply, but everything is exquisitely on the surface. I’m finding it hard to write about, perhaps because compared to Eraserhead there is so much less room for interpretations. Anyway, I loved it, and I can’t imagine wanting to watch it ever again.

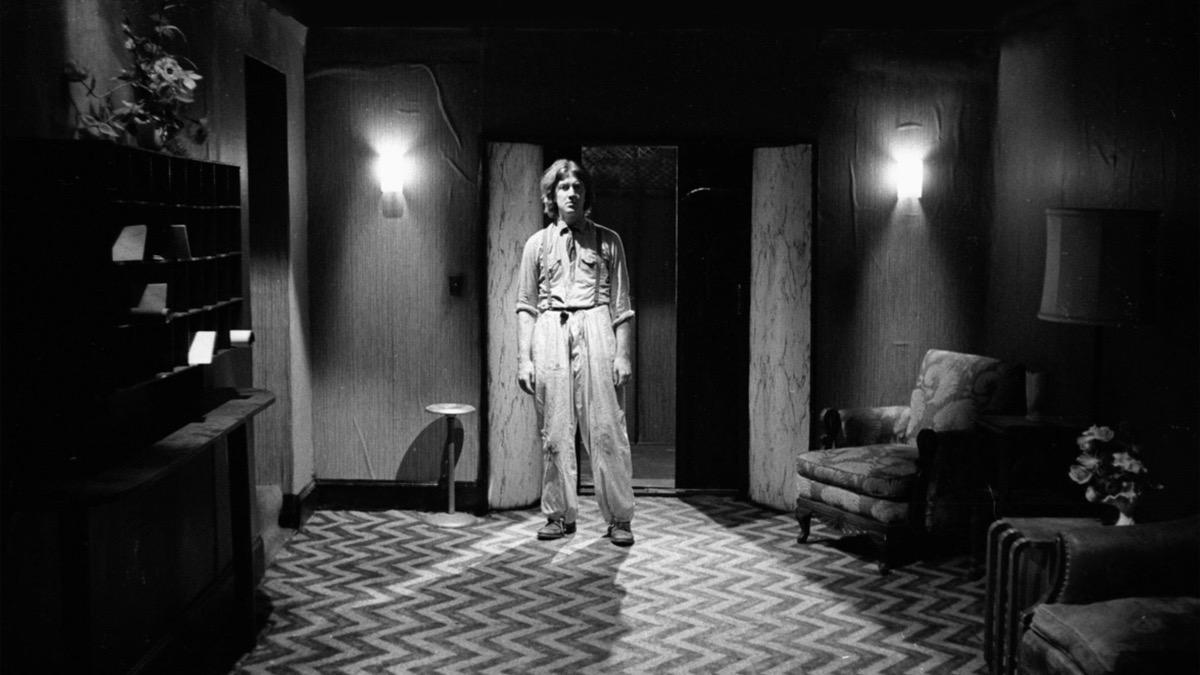

Eraserhead

Director: David Lynch

Release year: 1977

It’s surprisingly hard to see David Lynch’s Eraserhead in the UK, which means it is easy to avoid. To me the title was abstract and off-putting, as was its reputation as one of Lynch’s most experimental, gruesome works. The iconic black-and-white picture of Jack Nance as Henry Spencer always reminded me of Bride of Frankenstein and an older, artier film than I ever seemed to be in the mood for.

To watch it I had to buy a German Blu-ray, which came with an excellent documentary, Eraserhead: Stories, and all of Lynch’s short films up to that point. I also found a Kickstarter-financed interview film, David Lynch: The Art Life. Between those two documentaries you get a good sense of the man as an artist and filmmaker. He’s quite something. His ideas about art and the process of making really chime with me. There is also, of course, the video of him comparing the creative process to fishing, which is fun.

Lynch directed ten films – Eraserhead, The Elephant Man, Dune, Blue Velvet, Wild at Heart, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk with Me, Lost Highway, The Straight Story, Mulholland Drive and Inland Empire – and wrote them all too, apart from The Straight Story, which was written by Mary Sweeney and John E. Roach. He’s a true auteur.

I find his voice soothing, even though it has a grating quality, possibly because he seems like such a gentle, curious soul, and he talks directly, with great enthusiasm, about what he finds interesting. If I’m honest, this is the other reason I chose David Lynch right now – I intuitively know he has something that I need in my own work. Perhaps I’ll have worked it out by the end of the month.

Anyway, Eraserhead – reader, I loved it. It was so imaginative and pure and watchable and laugh-out-loud funny, which I didn’t expect at all. It’s a psychosexual puzzle about the horrors of unplanned parenthood, marriage, intimacy, capitalism, poverty, dreams – you can take it any direction you like. Jack Nance’s tragicomic helplessness and existential anxiety reminded me of comedic actors from the silent era. More than once he made me think of Oliver Hardy. The sound design is incredible, and the visuals are endlessly inventive.

I don’t want to write about what I think the film means. It’s going to stay with me, and there’s no point repeating what others have said. Watch it and make up your own mind. More than the film, the thing I’m most struck by is Lynch himself – how he works with his unconscious mind and processes his life through art. He says in one of his interviews that the past is always in the present, which I have also found to be true.

I’m looking forward to sitting with him, in my mind, at his studio in the Hollywood Hills, for the rest of the month.

Why read?

It’s been a tough year, and in the tumult of it, I stopped enjoying reading. Instead, I watched films, which are just as wonderful, but do a fundamentally different job. If you feel jaded with reading, or you want to think a little more deeply about what it means to read, I recommend the book I dug out this week, a collection of short essays, Stop What You’re Doing and Read This!.

I took some notes for myself and thought here was as good a place to put them as any.

‘A trained mind is a mind that can concentrate.’ – Jeanette Winterson

When we read a book we create a unique experience for ourselves from the words, like a musician does with a piece of music. The brain falls into a trance-like state and to our minds it is as if the events are really happening. Strong emotions alter the brain, so reading physically changes us, and in reading we can discover parts of ourselves we didn’t know existed. It can also simply be an escape from daily suffering. It’s a relief to find out other people have similar thoughts and feelings to us, and we are not alone.

It’s thrilling to be transported to another world. The right book is a question of taste and timing. It’s important to love language – this is where books are different from films. Words convey inner experience in a way that film cannot. We can inhabit novels and become friends with them. Poems can be life-saving to people in the depths of despair and sharing our experiences of reading builds groups and communities.

Tim Parks says modern life is fast and there is pressure to rush, but rushing ruins reading. The opening pages of a book show the author’s intent. Writers use the tricks of language to get into our heads, so don’t be a pushover and be ready to walk away. Pay attention and think critically. The perfect mode of reading is a kind of wakeful enchantment. Reading critically is a question of self-esteem.

Jeanette Winterson describes the imaginary world of books as ‘the total world’, holding the inner and outer as one whole. Time isn’t linear in books, just as it isn’t in memory, where we group things by meaning and symbolic power. For her, reading is a way of being at home in her own mind. It’s ‘a private conversation happening somewhere in the soul’. She says books work from the inside out and balance the work we have to do in the world to survive. Art (and writing) is a medium for the soul, so find books that have being, is-ness, vitality.

Spring arriving has given me a creative kick. April has been pretty meta literature-wise. I’ve been reading about reading, reading about writing, writing about reading and, of course, of course, writing about writing. It’s all good. The novel is taking the time it needs, and who knows, perhaps it also needs me to do a few side projects. The meta begat new ideas. I want to write about films through the summer and work on some short stories. (Between you and me, I’m hoping the novel will get jealous and push these projects to one side, but, you know, shhhh.)

I’ve been dreaming more this week and remembering them long enough to write down. I listened to a wonderful two-part episode on the films of David Lynch with the Pure Cinema Podcast, which got me thinking about my relationship with Lynch and what I know of his creative process. It’s given me a burst of energy. I’d forgotten how he swims in the unconscious, and many of his ideas align with what I’ve learned in my own practice.

I’ve only seen two Lynch films – The Straight Story and Mulholland Drive. I remember the splash Twin Peaks made on TV when I was a teenager, and I remember enjoying season one, but the second season was dull, and I didn’t finish it.

Anyway, what I’m trying to say is, in May I’m going to watch his eight films in order, from Eraserhead to Inland Empire. I don’t want to review them, but I do want to write something about my experience of watching them. That’s as far as I’ve got with it. I’ll stick links to the posts on Twitter #MayvidLynch.

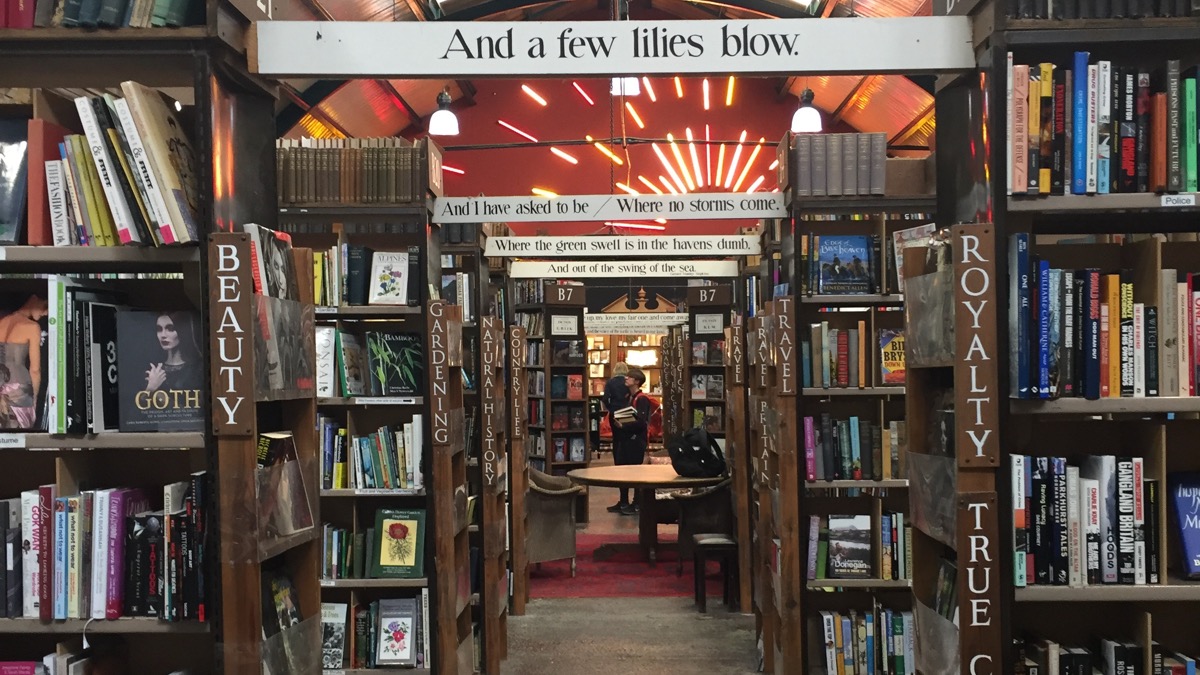

Something Wicked This Way Comes

I bought Something Wicked This Way Comes three years ago in a bookshop sale, in spite of the cover, which honestly put me off reading it for a long time. It showed a terrified, wide-eyed carousel horse looking down, about to trample the reader under its feet. When I did start to read it at the end of last year, I was surprised by the lyrical, slightly opaque language of the opening pages, and I put it down. It was so unlike the straightforward prose of Fahrenheit 451 (1953), I was disappointed.

I’d read Fahrenheit 451 three or four times over the years, but I didn’t know much about Ray Bradbury’s career or other works. I wondered what he’d written in the nine years between Fahrenheit 451 and Something Wicked This Way Comes (1962), and it turns out he tried to write a semi-autobiographical novel about his childhood, which became a short story collection, Dandelion Wine (1957), and he published other collections of stories he had written as a younger man in the 1940s. I’d like to read his biography, because reading behind the lines of Wikipedia, it looks like he spent most of the 1950s recycling older material for a new, much larger audience. He would have been in his thirties in that decade, and I wonder if he found that period frustrating.

(I’m possibly projecting. Megan Dunn writes brilliantly about her long relationship with Fahrenheit 451, and her own creative frustration in her memoir with Galley Beggar Press, Tinderbox (2017).)

Anyway, out of that decade, galloping out of the gate, or rather accelerating around the carousel, came Something Wicked This Way Comes. Bradbury had just entered his forties when this was published, and it gives a mostly-child’s-eye view of the arrival of an evil carnival in Green Town, Illinois.

A couple of weeks ago I decided to give it another go. I tweeted a picture of the cover, perhaps looking for some public accountability in making myself read what I knew was a classic, and I was thrilled by people’s replies with their own different-covered copies. Even in my small literary circle it was loved.

It’s a story about the perils of youthfulness and mid-life. Young teenagers Will Holloway and Jim Nightshade watch the Coogar and Dark carnival arrive in the middle of the night. In a series of breathlessly narrated, yet lyrically rich, set pieces, they see more of how the carnival works than they should and are hunted by carnival folk over a long late-October weekend. The carnival feeds on fear and pain, and tempts people with their deepest wishes. Only Will’s father, a janitor at the local library, himself full of doubt and regret, believes their story.

That accidentally reads a bit like blurb on a back cover, which is probably because I loved this book. The secret to getting into it was to read it fast and let the language pour over me, not sweating the sentences too much, and being carried along. Some scenes are all-time classics I’ll never forget — the boys hiding under the grill of the cigar store as the carnival marches through town; Mr Cooger being shocked under the policemen’s transfixed gazes; Mr Dark arriving at the library looking for the hiding boys.

Youth is hard, and getting old is harder. Every choice comes with a life not lived. My father was an older man, about Mr Holloway’s age when I was like Will, and now I am a father myself. This book hit home.

It’s Spring

This time of year is always strange. There is a drumbeat of family birthdays, including mine, and the pandemic has heightened the sense of time passing. My mother died at the end of February 2014, so this is seven years, unbelievably, since then.

Spring represents renewal. My father has had the vaccine, as has my sister and both my in-laws. I don’t know what my mother and grandmother would have made of all this if they were still alive. The so-far-successful rollout of the vaccines is making me feel cautiously optimistic for the first time since last March. Of course, that’s the other strange thing about this time – it’s a year since the pandemic hit. I remember the paranoia in my workplace, of people disappearing with ‘flu’, people trying to open doors with their knees (so they didn’t have to touch handles), and little coughs and widened eyes. I think I had it, but I’ll never know, and that mad month became a whole year of anxiety and physical withdrawal from regular life.

Finally, I feel hopeful. I don’t know what the rest of 2021 will bring, but my daughter goes back to school on Monday and will be with her friends for the first time since December. In three weeks time I will be able to drive to the beach and walk along the sand. My family and friends are okay. It’s Spring, and it feels like it.