Michael Walters

Notes from the peninsula

Welcome!

This is my little word garden on the internet—Michael Walters, author (it’s true!). I have a speculative fiction novel, THE COMPLEX, out with Salt Publishing, and I’m deep in the writing of a follow-up. I would love it if you gave it a try.

I use Bluesky to connect with people, Letterboxd to track films, and StoryGraph to track books. Follow me and say hello in all those places.

And if you want more of my thoughts on writing in particular, you can subscribe to my posts on PATREON. There’s a Weird and Wonderful tier if you want to support me with a donation, and that now includes notes on the novels I’m reading, but I post regularly to all patrons.

A flotilla of metaphors

Lying in bed this morning, between the alarm going off and me pulling back the duvet, it occurred to me that sentences can capture the high-level aspects of a story as well as the nitty-gritty. This isn’t a world-shattering realisation, and it isn’t like I’ve invented a vaccine or anything, but for me it was a little spark, a sympathetic prod, a loving poke even in the direction of writing enlightenment.

When the creative winds are not blowing, and you find yourself becalmed, those summarising sentences can be like flying a kite high enough to catch a draught that might pull your flotilla of metaphors to fresh coordinates.

Writing gland

Stephen King’s On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft is one of those books I keep coming back to, this time to stimulate my first draft writing gland and get my novel moving again. I’d run aground at twenty thousand words. King’s advice? Write every day and keep going. Thanks, Stephen. Annoyingly, he was right, and I wrote 500 words every day this week. Yay, me.

Even with this blockage removed, and perhaps because the blockage wasn’t there to fixate on, it was a tough week, the hardest emotionally since the pandemic started. This time we know it will be months, not weeks. Outside it’s cold, dark and icy, and I turn forty-eight in March. The life clock is ticking.

To inject some fun into things, I watched Tentacles, a B-movie Jaws ripoff starring John Huston (!), Shelley Winters (!!), Henry Fonda (!!!) and Bo Hopkins (?!). It was much worse than I hoped. Where [Piranha had Joe Dante to add some humour and irony]({% link _posts/2020-31-days-of-horror/2020-10-10-piranha.md %}), Assonitis is seemingly incompetent. All those great actors wasted. Where did the money come from to make this? I’m glad I watched it though, because I never take a complete punt on a film like this, and now I know what a terrible B-movie looks like.

Clearly a glutton for punishment, I went Thai aquatic horror next with Brian Yuzna’s Amphibious, a.k.a (which I only realised after a completely unnecessary battle axe was hurled at the camera) Amphibious 3D. My eyeballs were still seared from Tentacles, so as poor as the script and acting were, this felt like a banquet of cinema in comparison. The giant sea scorpion was memorable, and the Miskatonic University sticker on marine biologist Skyler Shane’s laptop made me smile. It had an odd tone, like a gory mix of Big Trouble in Little China and Pirates of the Caribbean. I can’t recommend it.

After those two stinkers, and also being primarily a writer of novels, it seems wrong to bring in 2020 Booker shortlisted Real Life here, but that’s how the week unfolded. Like real life, Real Life is impressive but left me frustrated. The book’s protagonist, Wallace, is similar to me in some ways (emotionally damaged, male, scientist) and not in others (he is black and gay). Over an intense weekend, we see his previous experiences and assumptions spark against those of his friends and colleagues. My problem with the book is too many times I felt overwhelmed by, and impatient with, the cattiness, games and histrionics of his friends and peers. Perhaps it’s where I am in my life. I’m glad I’m not in my twenties anymore. Perhaps I’m jealous — he didn’t even want to write a novel and wrote it in five weeks just to get his agent off his back. Damn it, Brandon, at least pretend it was hard.

It is, of course, Giallo January, and like Taylor, Dario Argento is prolific (yes, I see the pattern in my choices here). After Argento’s debut masterpiece The Bird With the Crystal Plumage came out in 1970, he released two more films in 1971 — The Cat o’ Nine Tails and Four Flies on Grey Velvet. The former is a sprawling crime mystery set in Turin and has a blind ex-journalist join forces with a reporter on a big newspaper to solve the murder of a scientist at a genetic research facility. The latter is more in keeping with Argento’s other work, where a serial killer torments a rock musician and makes him question his sanity. There are red herrings galore, and lots of over-the-top and super-camp side characters, but for me these films are about striking images and what can be done with a moving camera. They both drag a little in places, but more than make up for it in extended bursts of suspense and action.

Argento demonstrates the power of looking and framing what you see. Both Argento and Taylor create impressive works at pace. Yuzna is enthusiastic and professional, even when he must know the problems with his script. Assonitis is ambitious and knows what sells. Let’s funnel energy from these unlikely role models into the week ahead.

- On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft, Stephen King (2001)

- Tentacles, dir. Ovidio G. Assonitis (1977)

- Amphibious, dir. Brian Yuzna (2010)

- Real Life, Brandon Taylor (2020)

- Four Flies on Grey Velvet, dir. Dario Argento (1971)

- The Cat o’ Nine Tails, dir. Dario Argento (1971)

Slippery surfaces

I started the week with Blade Runner 2049. I was frustrated with it in 2017, but watching it over three nights at home, I’m more forgiving. It’s way too long. It looks beautiful, and it has some fascinating ideas, but the story is broken. The main villain disappears without much comment, and I didn’t buy the replicant rebellion, so the idea of K sacrificing himself had little emotional weight. It’s disappointing. There’s an interview in which Ridley Scott gleefully claims to have been heavily involved with writing the script, which might explain a few things. I did find K’s relationship with his home AI moving. She felt like the heart of the film. It’s a glimpse of what could have been.

(Am I doing weekly summary posts now? Perhaps I am. It helps me notice what impact the week’s books and films have had on me. Hand-written notes just get lost in the stream of ink on paper.)

My Year of Rest and Relaxation, by Ottessa Moshfegh, left me cold too. I admired it — the prose craft is superb, and it had funny moments, but I got bored and ended up skimming the final third. The unnamed protagonist had similarities to Eileen, Moshfegh’s previous novel, which I really enjoyed. This felt more like one of the art projects she satirises. It almost became another one of those books that snarled up my reading rotors in 2020, but I spotted the danger and switched to speed reading mode. I’m high-fiving myself for that.

From there, I jumped into The Man Who Saw Everything, by Deborah Levy, which was a lot more interesting. Her prose is impressive, with a formal air, possibly because she tends to write characters with academic backgrounds. I remember there being a surprising amount of dry economics and politics in Hot Milk, although that it’s been a while since I read that. She manages to make Saul Adler both sympathetic and unpleasant in his perfectly justified narcissism, and the ending felt suitably weighted and emotional. She makes the jumps in time pay off.

I closed the week with three sparky films. In Spontaneous, Brian Druffield somehow managed to make a film about high school students spontaneously exploding be funny, romantic, horrifying, sad and hopeful. There is a definite feel of a school shooting about the randomness of people dying in front of you, but the central relationship is sweet, and Mara is a fantastic comical and complex teenager (a stellar performance from Katherine Langford). It also feels right for COVID times.

The Woman Who Ran couldn’t be more different. In the suburbs of Seoul, Gam-hee visits old friends she hasn’t seen in years because her husband is away. She tells them she is happy, but this is the first time she has left his side since they were married, and we sense mixed feelings under the surface. It’s like she is trying on her friends lives to see if they are a better fit than her own.

Finally, swayed after a glass of wine by the superlatives in the Mubi description, there was All the Vermeers in New York, a weird, awkward independent film from 1990, that mixes a slightly grating jazz soundtrack with shots of New York, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, paintings by Vermeer, conversations between students who somehow share a ginormous flat in Manhattan, an aggressively out-of-place interaction between an artist and a gallery curator, and a stockbroker who has fallen in love with a student half his age. It’s one of those messes I’m glad I experienced, but I can’t recommend.

- Blade Runner 2049, dir. Denis Villeneuve (2017)

- My Year of Rest and Relaxation, Ottessa Moshfegh (2018)

- The Man Who Saw Everything, Deborah Levy (2019)

- Spontaneous, dir. Brian Duffield (2020)

- The Woman Who Ran, dir. Hong Sang-soo (2020)

- All the Vermeers in New York, dir. Jon Jost (1990)

Autumn and The Long Goodbye

In Ali Smith’s Autumn (2016), when discussing a piece of art, Daniel Gluck asks the young Elisabeth, ‘And what did it make you think about?’. I love the openness of that question. Interpreting art is about making connections. There is a passage where Daniel describes to Elisabeth a collage by a long-forgotten artist, and when I ask myself what Autumn makes me think about, my first answer is — a collage.

I had read that this was a contemporaneous novel, written very quickly over the summer of 2016, in the aftermath of the Brexit vote, but reading interviews with Ali Smith, it was more complicated than that. She had partly written another novel, which also made its way into Autumn, so she must have been writing new material into the structure and details of old material. The story jumps back and forth through time, so you are left with a sense of having looked through an artfully assembled non-chronological series of scenes, much like a collage.

This helped me with my work-in-progress, which slowed to a stop over Christmas. I can imagine Ali Smith standing over a canvas, sticking a scene here, a scene there, gleefully assembling pieces she had written out of order into a final draft. I’m envious of the flow state artists get into. Quick decisions. Instinct. Collaging also reminds me of how a jigsaw comes together. Repeating themes.

The Long Goodbye (1973) was released the year I was born. I guess I’m thinking about births and deaths — I heard a vicar on TV describe the circle of life as ‘hatched, matched and dispatched’ — and time passing. It’s a stunning film noir. Elliot Gould is a pathetic, melancholy Philip Marlowe, pushed and pulled around, desperately loyal to his friends. By the end, that loyalty is exposed as his weakness. The climax is surprising and cathartic. The story’s character work pays off. It’s like a novel in the way Marlowe constantly talks to himself, revealing his inner world. No matter what eccentric scene he comes across, he reflexively says, ‘It’s okay with me’. Until finally, it is not okay.

- Autumn, Ali Smith (2016)

- The Long Goodbye, dir. Robert Altman (1973)

My 2020 in books

I’ve had a tough year reading books. I fell into the trap of seeing reading as work and lost the joy of it. I filled the story gap with films, but thanks to a throwaway Goodreads challenge (35 books in 2020), managed to keep going. Writers aren’t supposed to admit to not enjoying reading. It’s a truism that reading is a necessary part of writing, but in agreeing to go to a new book club, reading Adelle Stripe’s Black Teeth and a Brilliant Smile became actually necessary. I would never have chosen it, but I’m happy I did, because the writing was brilliant, and showed a way to use fiction to tell the story of a real person, in this case the playwright Andrea Dunbar. Dunbar died in 1990 from a brain haemorrhage. It made me think about poverty, alcoholism, bad parents, and my own working class roots.

From there I turned to a H.P. Lovecraft collection, The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Tales. Most books I choose are novels, and if I do choose short stories they tend to be smaller collections, so this hefty tome, with several novellas of increasing conceptual density, became a serious obstacle. Instead of putting it back on the shelf, I let it sit on my desk making me feel guilty, because it turns out part of my personality requires that I finish books I start. I’ve always been a one-at-a-time book guy, and if a book becomes dull I skip and scan ahead, but those tactics didn’t work here. I ran aground just over halfway and stayed there until the end of March.

Stoner, John Williams’s classic, got me off the rocks and back on track. It’s one of my favourite books of the year, a view of a man’s life from birth to death, concentrating on his time as an academic at the University of Missouri — a simple man with a straightforward life, and all the wonders that entails. At the end of April I hit another book that knotted up my reading propellers — Rebecca, by Daphne du Maurier. I really didn’t like it, even though my peers seemed to unanimously love it, so I kept trying to finish it, and I kept sabotaging my own efforts. A grim period. Perhaps that first lockdown was getting to me. Eventually, like Lovecraft, I put the old woman aside, and switched to a burst of science-fiction.

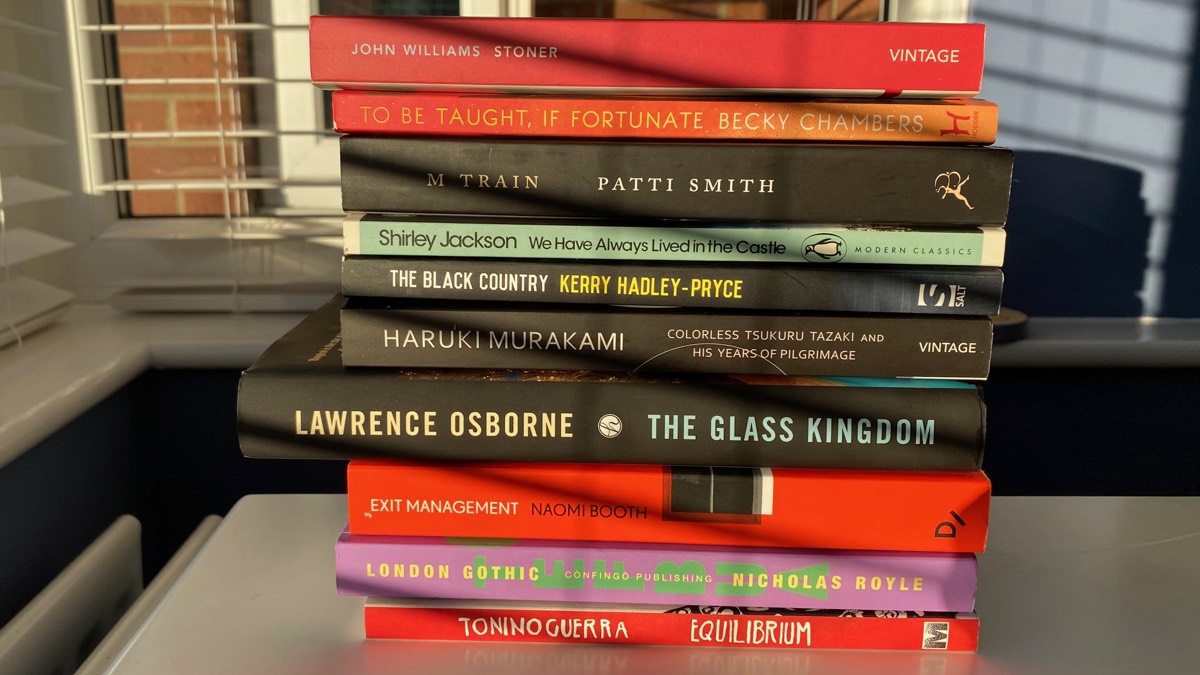

Someone recommended To Be Taught, If Fortunate, by Becky Chambers, on Twitter, I liked the idea of a novel about astro-biologists, and it was short. I’ve always found short novels to be the best route out of reader’s block. Each chapter sees the crew of a deep space mission to investigate life in the furthest reaches of space stop on a planet and study its biological wonders. The pleasure is in the atmosphere, descriptions and crew dynamics. From planet Chambers, I ventured to Shirley Jackson (We Have Always Lived in the Castle), Patti Smith (M Train), and Kerry Hadley-Pryce (The Black Country), three voices that couldn’t be more different, but lit up my summer. In August, I read Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage, by Haruki Murakami, a familiar style, and a familiar Murakami protagonist, but expertly done.

My third literary roadblock of the year was Ted Chiang’s Stories of Your Life and Others. It’s lauded as one of the best science-fiction story collections… ever. The film Arrival, which I loved, was based on one of its stories, Story of Your Life. A co-worker raved about the collection to me. But, oh, how I hated this book. It wasn’t a rational reaction. The stories were beautifully crafted, and I admired them, but the ones I read were cold, empty things. I can’t think of a book that has ever repelled me so strongly. I couldn’t allow myself to give up, so it became this noxious presence on my desk for weeks and weeks. After a while I resented its very existence. I despised it. I wonder now if I was putting on that book something of myself that I was struggling to bring to consciousness. I must have been. The book was praised, successful, expertly crafted, oh-so-clever, but the characters were ciphers for ideas, and there was no discernible heart. I found the opening stories so cold they somehow froze my mind so I couldn’t continue. Eventually, I let the book go. I’m still not sure what my emotional storm over it was about.

This left me running well behind schedule in November. Luckily I hit a rich vein to get me over the finishing line — The Kingdom, by Lawrence Osborne, was a cold thriller set in a humid Singapore, and inspired me to get back on the writing saddle. Exit Management, by Naomi Booth, reminded me what amazing things can be done with voice. London Gothic, by Nicholas Royle, is another of his story collections around a theme, and testament to good prose, writing about what you love, and playing the long game. Anf finally, Equilibrium, by Tonino Guerra, a firecracker novel of ideas that got me thinking about literary form and the role of history in character’s stories.

That was my 2020 in books. Next year I want to read 60 books (!), some newly published (yes), and most importantly, enjoy reading more (YES). (Note to self. Stop believing hype and make up your own mind. If you’re stalled or bored, put that fucker down and find something you’re into. It’s not like there’s a book shortage. Ffs.)

- Black Teeth and a Brilliant Smile, Adelle Stripe

- Stoner, John Williams

- To Be Taught, If Fortunate, Becky Chambers

- We Have Always Lived in the Castle, Shirley Jackson

- M Train, Patti Smith

- The Black Country, Kerry Hadley-Pryce

- Colorless Tsukuru Tazaki and His Years of Pilgrimage, Haruki Murakami

- The Kingdom, Lawrence Osborne

- Exit Management, Naomi Booth

- London Gothic, Nicholas Royle

- Equilibrium Tonino Guerra

Language muscles

Having watched so many films this year, next year I want to get back to reading novels. Films do play into my writing practice. They show me patterns of story, character arcs, themes and dialogue, as well as feed my imagination with striking imagery and interesting locations. Fiction has these, but is the equivalent of sheet music, so it is on me as the reader to make them real in my mind, and adds all the wonders of language — point-of-view, voice, descriptions, internal experiences, and literary forms and techniques. I’m finding reading difficult again because I’ve neglected books. Reading fiction requires reading muscles, and writing fiction requires writing muscles. To get through the horrors of 2020, I’ve let both atrophy.

Fiction also provides distance. I love reading a couple of pages and stopping to look out the window, so the words can sink in. I drive the pace when I’m reading. Films are designed to be watched in one sitting, preferably in a cinema, and the pace is out of my hands. I can reflect along the way with a book. It’s a dozen hours or more of story in small chunks. After a film I have to process the whole, and if I missed a key line of dialogue, or I’m distracted for a couple of minutes, it might leave me with a completely wrong understanding. I often leave films feeling drained, physically and emotionally, especially the longer or more intense ones.

All of this is to say, I need to get a better balance of literature and film in 2021. Language is the raw material of my art. But films are still terribly important to me.

If you listen to podcasts and love films, I can’t recommend enough the Pure Cinema podcast, with Elric Kane and Brian Saur. This is one of the things that have kept me going this year. Walking the same streets every day would be so dull without their voices in my head. Similarly the Projections Podcast, hosted by Sarah Kathryn Cleaver and Mary Wild. Both podcasts have given me a film education, and all I’ve had to do is walk around my neighborhood.

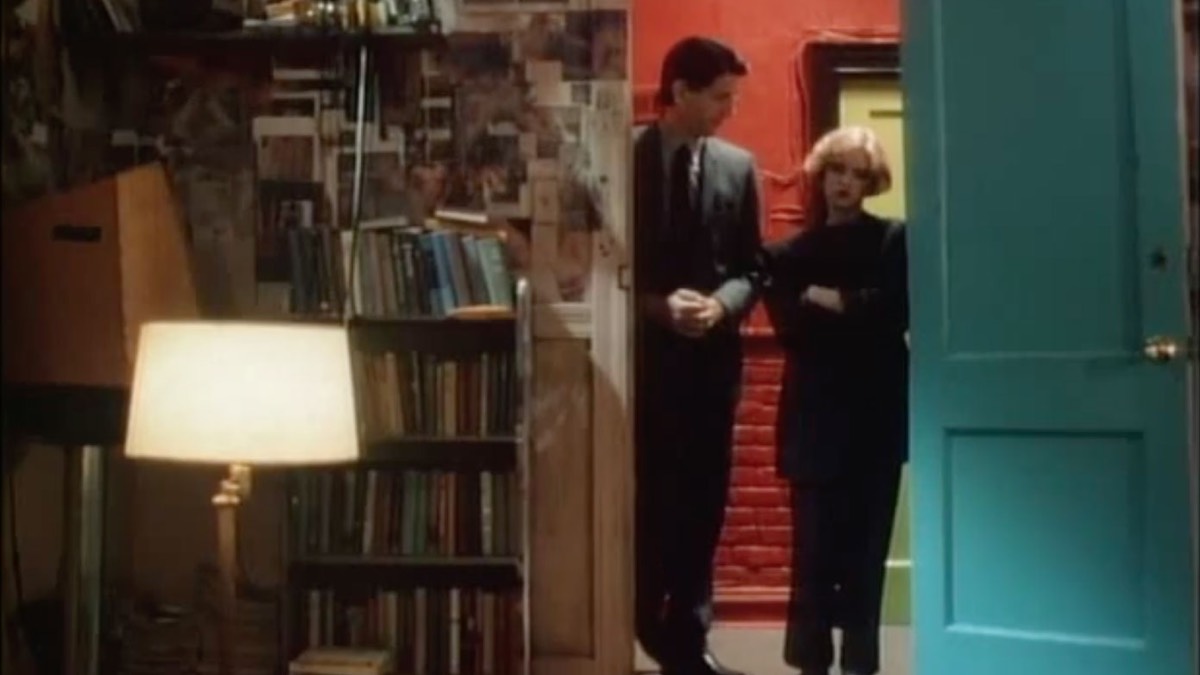

It was Elric Kane’s recommendation that led me to buy the spectacularly strange Heart of Midnight (1988) DVD (it is criminally unavailable streaming). Jennifer Jason Leigh, in one of her earliest roles, plays Carol, a young woman who inherits her dead uncle’s derelict sex club. It’s weird and icky, but Leigh is superb, it has bags of ideas, the club location (The Midnight) is inspired, and by switching between reality and dreams, it has some glorious surreal imagery. It’s a cult wonder.

Equilibrium is a novella by Tonino Guerra, first published in 1967, but republished in 2020 by Moist as the first in a ‘trilogy of alienation’. A graphic designer in Milan heads to a villa on the east coast of Italy to come up with ideas for a font for a kitchen company. The abstractions of his life serve to distance him from his feelings about the second world war concentration camp he survived, but he finds himself adrift and increasingly manic in the modern world. He is fearful and neurotic, creative and successful, but he knows his work is ultimately pointless. It’s like a Charlie Kaufman film on 10x speed, because at times each line is another decision or idea that distracts him, and the reader. It reminded me of Slaughterhouse 5. The nameless protagonist is looking for some sort of equilibrium, but the forces assailing him are too powerful, and he craves the repetition of his trauma. Perhaps he finds some peace in his art.

Staying with European writers, I had another go at The Art of the Novel, by Milan Kundera — a series of essays on what he is trying to do with his novels. It’s a tough book because Kundera loves philosophy and has a deep knowledge of literature. I do not (to both). Last time I attempted it I didn’t finish the first essay, but this time I got over halfway through the book. I’m with him on celebrating life’s complexity in novels and not going the easy route, but I write (and read) because I love stories, and I love characters, whereas he loves the ideas more. His characters are almost pure ciphers for the problems he is thinking through. That’s not my bag.

As if to prove my point, I also watched The Grinch (2018) and Rare Exports: A Christmas Tale (2010). Both show the shadows of the Christmas season, but where the Grinch is (very) cute and grumpy, the Rare Exports’s Santa Claus is a giant horned devil encased in ice, and his elves are naked old men who steal children in the night. I loved the gritty portrayal of the lives of Finnish reindeer hunters. It’s an antidote to the Coca-Cola Christmases it makes fun of.

And finally, to round this mammoth post off, De Palma (2015). It was fascinating, if a bit shallow, and is simply Brian De Palma telling the stories behind every film in his filmography. The interviewers edit their questions out, and show illustrative scenes from the films, so it’s De Palma’s voice for two hours. Fortunately he’s a charismatic, likeably forceful interviewee, and is not afraid to speak his mind, which gives the film spark, but the time flies by, so it’s a whistle-stop tour, which is a shame.

Films:

- Rare Exports: A Christmas Tale (2010), dir. Jalmari Helander;

- The Grinch (2018), dir. Scott Mosier, Yarrow Cheney

- Heart of Midnight (1988), dir. Matthew Chapman

- De Palma (2015), dir. Noah Baumbach, Jake Paltrow

Books:

- Equilibrium, by Tonino Guerra, Eric Mosbacher (Translator)

- The Art of the Novel, by Milan Kundera, Linda Asher (Translator)

Why do I write here?

I’ve written more posts on my blog in 2020 than ever before. It was tricky to start with — I had to find a new voice and get in a groove. As the year ends, and I begin to think about 2021, I find myself wondering, are they worth the time I put into them? I might get a few extra passersby from the links I post to Twitter, and so might sell a handful of books, but that isn’t why I write here. Why do I write here?

I’ve mostly written about films this year. Doing that has definitely deepened my experience of them. The act of writing makes me think more thoroughly. An essay starts with a title, a question, and I unconsciously have questions when I begin a film post. It’s only in writing this that I realise what they are. Why did I choose the film? What do I think about it? How does it make me feel? What did I really like about it? What memories does it evoke? How does it link to what is going on in my life right now? What didn’t work? I’m not interested in writing about how the film got made, where it fits in a director’s filmography, its box-office takings, or whether it got good reviews. I’m looking for a personal connection.

I don’t think of my posts as reviews because I’m looking for what is useful to me, and I’m biased towards my interests. Writing helps me pull out of other people’s creative work something of myself, from my unconscious — ideally for my own work-in-progress. That’s a high bar. Mostly I manage three or four paragraphs, with a brief synopsis, and a few things that struck me. I’m a devil for putting myself under unnecessary pressure, which helps get them written, but maybe keeps me in the experiential shallows. However, as in most things, something is better than nothing.

In the New Year I want to do things differently, write more about the connections between films and books, be more specific about what I’m looking for, and play with this blogging voice. It doesn’t have to be this way — this voice. There are many ways I can do this in 2021. That’s exciting.

London Gothic, Nicholas Royle

Author: Nicholas Royle

The protagonists of London Gothic are walkers, art lovers, film buffs and train nerds. They are loners, in the main, fascinated by urban spaces and routes between places. Through their eyes, we see the people who haunt the cafes, galleries and pubs of various parts of London, and we often go back to their houses, where we see their odd collections of things, or attempts at black magic. Sometimes they kill people, and sometimes we suspect they killed someone, but we’re not quite sure.

Some of these stories are published here for the first time, and others are older, with a couple reminding me strongly of his 2000 novel, Director’s Cut, which has London’s cinemas and underground stations at its heart. He can write straight prose like a dream, but he also plays with form, like in The Old Bakery, where a disgruntled editor makes increasingly bitter notes on a press release for an artisan bakery, and Artefact, with its six different points-of-view on a man’s innocent attempt to get his VHS tapes transferred to a digital format. If you like unsettling, dryly funny writing, then you can’t go wrong with this collection. It makes me miss London, even with its haunted houses and serial killers, especially now that the virus means I can’t go there.

As a final note, I want to point out that Nicholas Royle edited my novel, The Complex, and he recently published my short story, Signal, with Nightjar Press. The world of blurb, book bloggers and reviews can seem a little murky, and while I would be cynical about an author enthusing about his editor’s work, this post was written sincerely.

She Dies Tomorrow (2020)

Director: Amy Seimetz

This isn’t a horror film, though it is marketed as one. The camera is often still as figures move towards us, faces blurred by lights or shadows, and this does create a sense of dread. Much more of the film is observing Amy as she says goodbye to the world, stroking the wooden floor of her new house, and pressing her cheek against its walls. The story jumps through time, allowing us to piece together the events that have led to Amy’s last day. It’s a tactile, sensual film, slow and beautifully acted, but it does invoke anxiety.

It opens with Amy telling her friend Jane that she knows she is going to die the following day. Jane is a fast-talking, anxious person, and is only half-listening to Amy’s words, but they slowly sink in, and when they do Jane begins to believe that she is also going to die the next day. The film becomes a succession of conversations, the idea spreading from person to person, with coloured lights flashing that only they can see, so we don’t know if it is an alien invasion, a virus, a mass delusion, or something else.

It’s affecting, but also mordantly funny in places. Different people react in different ways to their fast approaching death, some doing terrible things, others simply telling each other the truth. The idea of the film lingered in my mind. We’re all going to die. Perhaps even tomorrow.

Director: Kiyoshi Kurosawa

I couldn’t resist another film by my new favourite director, Kiyoshi Kurosawa, care of my Mubi subscription. Knowing a film I fancy is going to disappear in a few days makes me create the time to watch it. It’s an interesting way to beat the paralysis of too much choice. I’d read that Kurosawa was an eclectic director, and this film proves that. Even though there are a couple of scenes that play on Yoko’s fears, it is mostly gentle, amusing and sad.

Atsuko Maeda’s Yoko is a mesmerising presence. She is a reporter for a Japanese travel programme that is making an episode in Uzbekistan. The crew keep their distance from her, making her do ridiculous, unpleasant things, like riding a violently spinning fairground ride over and over again, so they can get the right camera shot, and pressuring her to eat a rice dish from a street vendor even though it is not fully cooked. She is a trooper and does everything she is asked. But once the filming is finished, she goes on mini adventures, getting lost in the streets of whichever town she is in. Her job is unfulfilling, and she feels adrift.

Where Japan is surrounded by water, Uzbekistan is landlocked, and the crew’s translator, Temur, tells Yoko that he is envious of her living near the sea. He sees it as freedom, but for her it is dangerous. She is a fearful person, and Kurosawa makes her everyday experiences in Uzbekistan feel threatening. Slowly she realises her fear causes more trouble than it is worth.