Michael Walters

Notes from the peninsula

Welcome!

This is my little word garden on the internet—Michael Walters, author (it’s true!). I have a speculative fiction novel, THE COMPLEX, out with Salt Publishing, and I’m deep in the writing of a follow-up. I would love it if you gave it a try.

I use Bluesky to connect with people, Letterboxd to track films, and StoryGraph to track books. Follow me and say hello in all those places.

And if you want more of my thoughts on writing in particular, you can subscribe to my posts on PATREON. There’s a Weird and Wonderful tier if you want to support me with a donation, and that now includes notes on the novels I’m reading, but I post regularly to all patrons.

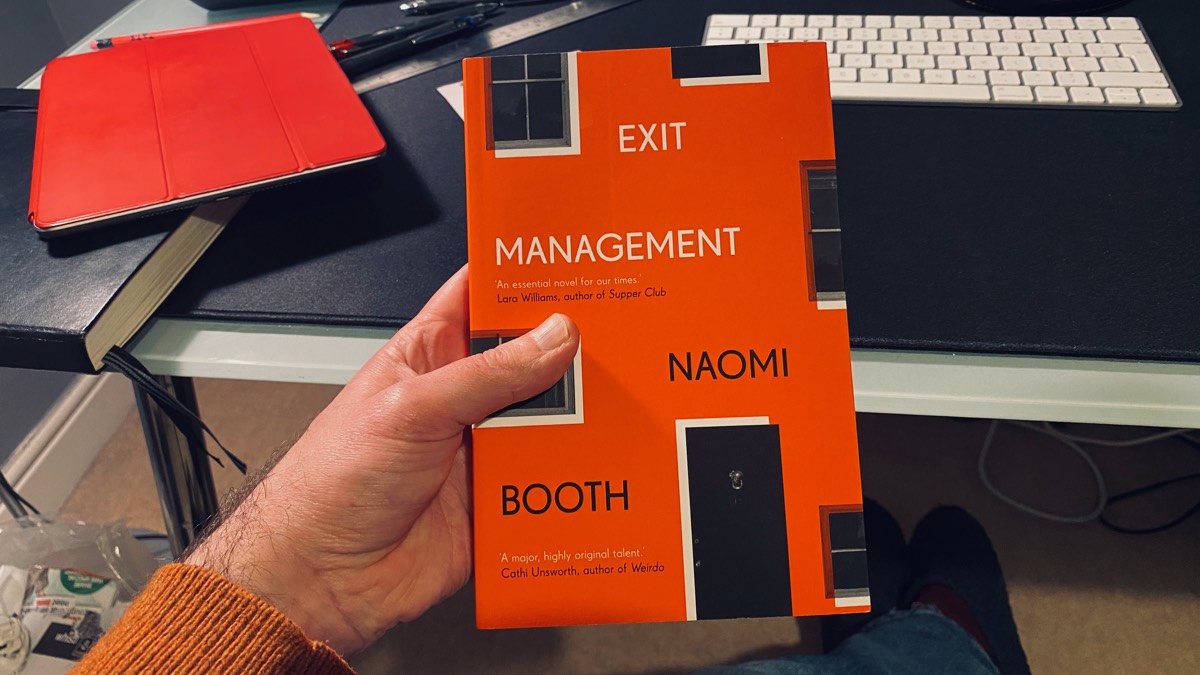

Exit Management, Naomi Booth

Author: Naomi Booth

The term ‘exit management’ is one Lauren’s HR consultancy uses as a euphemism for helping their clients to fire troublesome employees. Lauren is exceptional at it, and is highly valued by her monstrous boss, Mina, for her emotional control and ability to get the worst jobs done. Lauren meets Callum by colliding with him outside one of the expensive houses he is paid to look after. She thinks it is his, but it is actually owned by the terminally ill József, Cal’s favourite client and father figure.

Lauren, Cal and József’s stories intertwine. Each had challenging childhoods of different kinds. We see Lauren and Cal’s points-of-view in alternate chapters, with the old man’s voice coming from Cal’s love of hearing József talk. He worships József, who is happy to bring his parents’ memories back to life for Cal. We hear about Hungary’s role in the second world war, the fall of Budapest, and the fate of his mother, but he also educates Cal in classical music, paintings and culture. Cal is so close to József, that when Lauren thinks József is his father, he doesn’t correct her.

The prose style is brilliant, alternating between Lauren’s slowly fragmenting sense of control and Cal’s mixture of deep care for others and self-loathing. For all their front, both Lauren and Cal are from working class estates, and while József might be clear-eyed about what he needs from Cal, Cal and Lauren are driven by a mixture of ambition and more ambiguous unconscious desires. Anxiety is such a rich playground for playing with language. Where József seems to have found a way to live with his family’s history, Lauren and Cal’s family dramas play out in the present. Plenty can go wrong in the grey areas of what is assumed and not said.

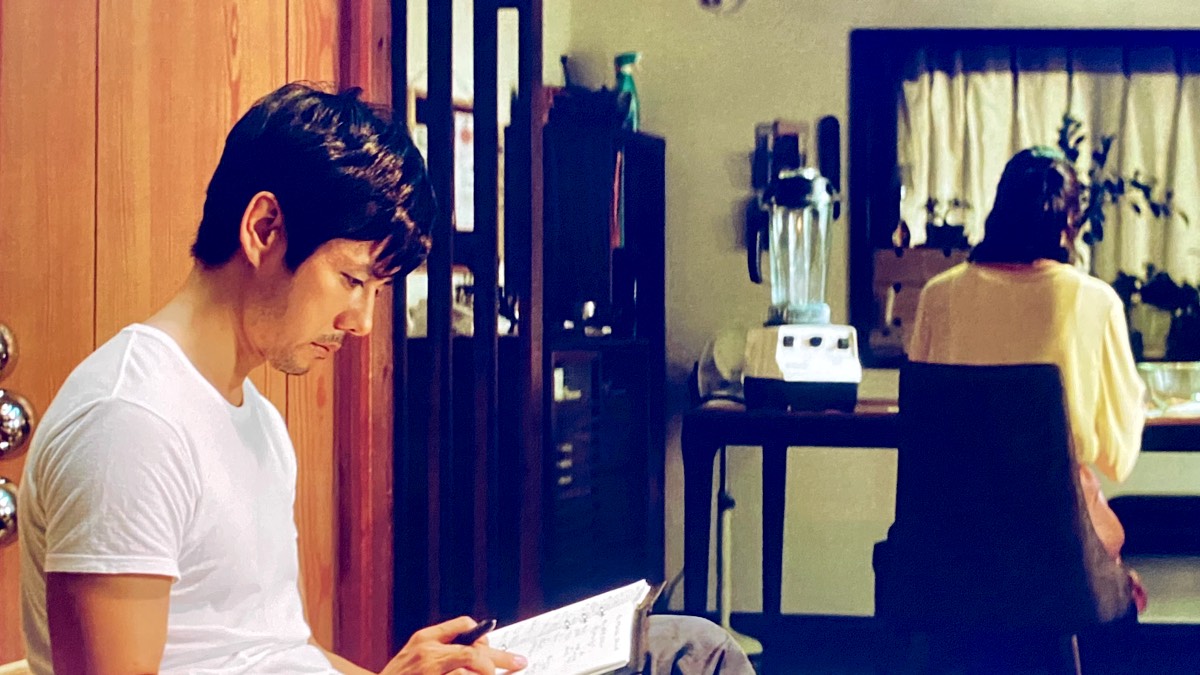

Director: Krzysztof Kieślowski

Tomek is nineteen, lonely and living with his possessive godmother in a Polish apartment block. Every evening he learns languages in his room until Magda, the woman he is spying on through his telescope, comes home from work. She is an artist and seems to be living a colourful life. Tomek thinks he is in love with her, but his attention becomes harassment. One day he realises he has gone too far and tells her what he has been doing. The ensuing confrontations teach them both a lesson about love.

Magda’s well-lit flat is full of paintings, materials and interesting objects. When she brings lovers home, Tomek watches until he can’t bear it anymore. His room is small, a child-sized room for a grown man, and his godmother’s flat is old-fashioned and dark. When he eventually declares his love for Magda, and she discovers how far Tomek has gone in his obsession with her, she tries to teach him that there is no such thing as love, it is simply the sexual impulse. The lesson humiliates him. He seems to want nothing from her and is content just to be near her. His love is both inappropriate and pure, unlike his godmother’s love for him, which is built on a disturbing, smothering selfishness, that keeps him stuck with her.

I remember buying Kieślowski’s Three Colours: Blue on VHS in the mid-nineties and carrying it from flat to flat as I worked my way through every rental property in Swansea. I travelled around Europe with a railcard while at university, and the Three Colours trilogy were released around the same time. They were the first foreign language films that I loved, and amongst the first handful of films that seemed outside my family’s experience, by which I suppose I mean my father’s, and so were mine alone. I was graduating from films like Die Hard and Alien, to Miller’s Crossing and Lone Star. Instead of action, I began to value dialogue, characters, imagery and subtext. I don’t know what I would have made of A Short Film About Love when I was in my early twenties, but I’m glad I discovered it now.

Creepy (2017)

Director: Kiyoshi Kurosawa

The films of Kiyoshi Kurosawa were a revelation to me in October. I started with Pulse (2001), then went back to Cure (1997), and both were masterpieces. Twenty years after Cure, Creepy (2017) is in a similar mould, playing with the framing of scenes to heighten uncanny feelings and making everyday events seem disturbing. Like in Cure, Kurosawa uses the charisma of psychopaths to drive the story, and Masahiro Higashide’s Nogami is a fascinatingly unpleasant creation.

Detective Takakura is a criminal psychologist. After he is wounded by an escaped psychopath, he retires to be a university lecturer, but when an ex-colleague comes to ask him for help on an old case, he is drawn back into police work. Meanwhile, his wife Yasuko is trying to make friends with neighbours after moving into their new home, but the man next door, Nogami, seems to have no social skills and odd ideas about personal boundaries.

The characters are mostly alone and focussed on their individual lives. The source of Nogami’s weird power over people is never explained, which means it’s hard to believe the characters would make some decisions they make, but that’s not to take away from the skill of the filmmaking. I don’t know Japan well enough to know if Kurosawa is making a point about Japanese society, but when there is a predator camouflaged nearby, without a village to shout a warning, people can be picked off, and that applies everywhere.

November culture

It’s good to play around with your projects and try new things. I still suffer from a degree of imposter syndrome, and I probably always will. That’s partly a working class thing, but it’s also because I didn’t study literature or writing until I was well into my thirties. At this point in my life, nobody is going to give me a reading list. I have to create my own structures. I want to be more conscious of how the books I read, and the films I watch, play into my writing. That’s why I’m trying new things with this blog.

After watching so many films in October, I was desperate to read a book again. I chose The Glass Kingdom, by Lawrence Osborne. It follows the residents and workers in an expensive Bangkok apartment complex, after the arrival of Sarah, a serial con artist with a suitcase full of cash. The women Sarah falls in with are all escaping something and in different ways unengaged with the world round them. As the story unfolds, the city and its citizens impinge more and more into the lives of the privileged women. It made me think about how I approach point-of-view. Osborne breaks all the rules of holding one viewpoint at a time, and doing that makes it feel less personal and more like Bangkok is telling the story. His descriptions are brilliant. It’s bleak and impressive, but a little cold for my taste.

I decided to go all-in on Mubi in 2021 and bought a subscription. I started with Two Days, One Night, in which we meet Sarah, who works at a solar panel factory somewhere in France, and is suffering from depression. Her co-workers are forced to vote between keeping her on or having a substantial bonus. After finding out on a Saturday morning they voted for a bonus, the rest of the film follows her attempts over the weekend to convince each of her fifteen co-workers to change their minds. Everyone is on the poverty line except the factory boss, who doesn’t care about the fallout. The vote pits employees against each other. The interactions are sometimes brutal, sometimes empathic, but always understated. The film rewarded my patience.

In contrast, Spider-Man: Into the Spider-Verse was a joyous experience from beginning to end. It’s fun, has emotional depth, and is easily one of my favourite films this year. Other films I watched in November, in descending order of enjoyment: Finding Vivian Maier (2013), Bruce Springsteen’s Letter to You (2020), Color Out Of Space (2019), Opera (1987), Eames: The Architect and the Painter (2011), Transamericana (2020).

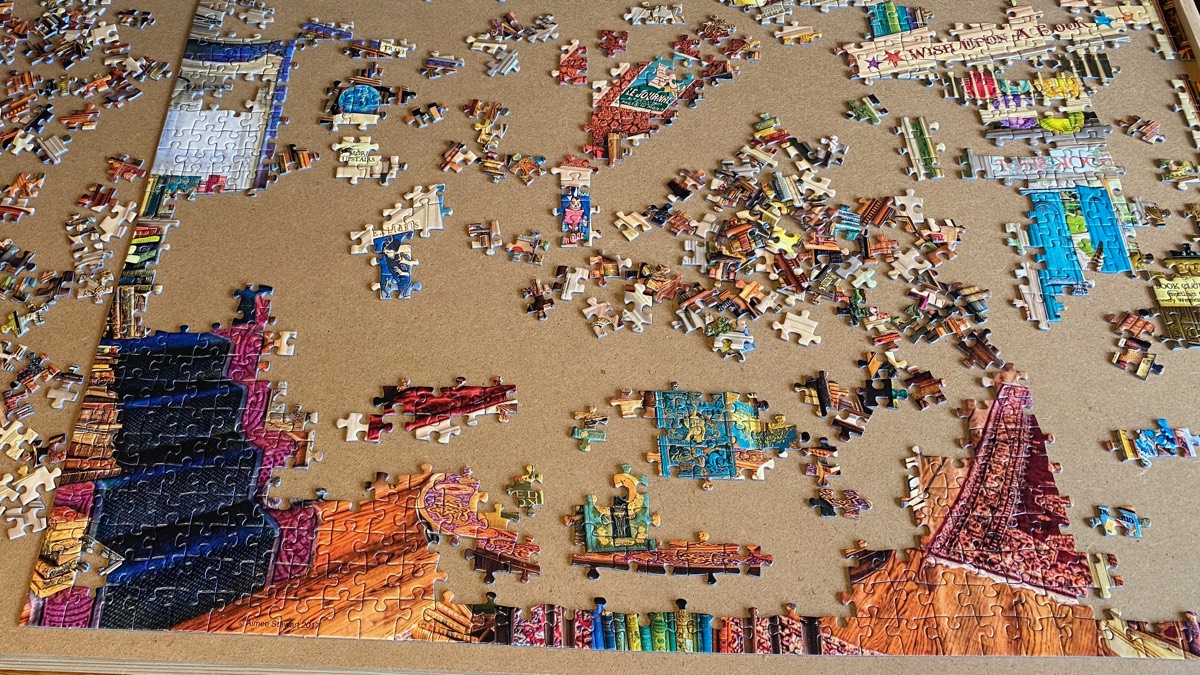

Jigsaws

My mother loved to do jigsaws. She would stay up late, after every one else had gone to bed, and do them on the dining table, which is also where she would do the bookkeeping for whichever company she was working for at the time. When she died, I found all the lists and accounts she kept for the household budget, and I remembered how she showed me how to keep track of my spending when I went off to university. She was renowned for balancing complicated accounts to the penny with only a calculator, pen and pencil, even after computers could do it all much faster. That was the jigsaw energy. She always needed things to be right when it came to her work.

I see that tendency in myself. When I do a jigsaw, I can feel my mother with me, and that’s comforting. I can let life flow over and around me, and I’ll never know now whether she was able to do that, but when something feels important, and I set my mind to it, I need it to be done to the best of my ability.

For Christmas last year I bought my daughter a jigsaw of a book shop. Facing a long November and December in another lockdown, I dug it out again, and bought a puzzle board to put it on, so I could push it under the sofa between sessions. (That didn’t work out, it turns out our sofas are all too low to the ground for the board to fit. It’s still useful.) As I’ve worked on it, painfully aware of the guilt I’m feeling about not working on my next novel, it’s become clear I fight my natural instincts. I make creativity more painful than it needs to be.

There are parallels with writing in the way I do jigsaws. I start by turning over all the pieces and looking for the edges. My mother taught me that. The edges provide a boundary. Then I look for the vivid, smaller sections, which are easier to find in the mass of pieces, and put them in roughly the right spots. At some point these sections connect to each other, or most thrillingly to the edges, and things speed up. By this point, my mind has spent enough time on the problem to begin to see connections before I consciously notice them. My fingers move to a piece without knowing why, and it fits somewhere unexpectedly. The whole assembles itself because I’m fully engaged, and the power of my pattern-matching mind, which I undoubtedly got from my mother, shines though.

Don’t get me wrong, that isn’t how I wrote my first book, and I’m not sharing my jigsaw-as-creative-writing metaphor because I know it’s right, but it might help me unlock my current work-in-progress, which also seems to be waiting for when I can sit at a cafe table again, where I’ve always written most of my words. The jigsaw energy and writing energy is surely also linked to the way I write software. It’s human to want to assemble patterns out of what seems like chaos. My problem-solving mind craves patterns. Anyway, that’s what I wanted to say about jigsaws.

Creativity 2.0(.21)

I’m in a fallow period, pottering around, looking for the next thing. I started a jigsaw, read a novel, watched the first half of Homecoming (Season 1, with Julia Roberts), listened to podcasts on my walks, and wrote in my notebook. Work was busy, and working from home I find it hard to switch off. I’m easily distracted. The US election sucked a lot of energy out of me. The news is everywhere now. Since finishing #31DaysOfHorror I’ve lost momentum in personal projects. That groove was a powerful source of creative energy.

Finally, though, I’m beginning to feel more centred. Within a couple of weeks, 2021 has gone from being the beginning of the end of things, to the beginning of something new — Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, a COVID-19 vaccine, the end of Dominic Cummings — these are all excellent for my mental health. The world is starting to feel safer.

I now know I can watch a film, make some notes about it, let it simmer in the back of my mind for a few days, then edit it into a decent piece of writing, and I can do that several times a week if necessary. That’s new. I’m not sure what those #31DaysOfHorror blog posts were. They felt like reviews, but I didn’t want to give an opinion on whether films were good, bad, or worth someone’s time. Instead, I tried to find what I liked about each film, then connected it with previous films or my own experiences. I felt obligated to provide a brief synopsis, perhaps because I always had the reader in mind, and they might not have seen the film. I wanted each post to make sense and stand alone.

A handful of people read them. That felt good. The one-film-a-day structure was a potent catalyst for making it a habit, as was posting a link to the post on Twitter. I was pretty wrung out from watching so many films in such a short period. I did love it, but after I’d finished, once I’d let myself decompress, it felt like a massive relief. However, I engaged more deeply with films knowing I had to write about them — that was the power of the challenge, and the public commitment that came with it.

I stopped watching films and writing blog posts completely in November. Drifting creatively is useful, but I’ve learned that without a project, eventually I lose sight of the coastline of my true interests and drift out to sea. I’d like to keep the bits that worked from #31DaysOfHorror, but make it less intense, more sustainable, and more aligned with my current goals.

Posting to my blog every day kept me accountable. That was my measure of progress. Looking back at those thirty-one posts I see what I achieved, and I feel proud of a good creative project. Having a page on my website pulling those posts together makes it feel coherent, just like seeing The Complex and Signal existing in the world does.

My next novel is plodding away in the background. I sit with it for up to an hour every morning. Some days I write a hundred words, occasionally I write none, but on other days I might write as much as five hundred. It’s intermittent and slow-going. Publishing short blog posts and posting them on Twitter — hell, just posting on Twitter and getting a few likes — gives me a feeling of accomplishment, and a dopamine rush writing a novel can’t compete with day to day.

A short story is a month’s work for me, and a novel is years of effort. This novel might never get published and only be read in three years time by one diehard fan willing to read an 80,000-word .docx file. I love you, man, but if the Time Wizard showed me his crystal ball, and that was how it was going to be, I’m not sure if I would go on. The hope of being published and having my work exist on its own terms in the world is a sustaining force. Without that hope, I’d like to think I would still write stories, because it serves some internal purpose, but honestly, I don’t know.

That’s what I’m competing with in my head. I don’t want my writing practice to feel leaden and dull. I’m writing good sentences, even though it is difficult work. Writing The Complex, I had the structure of a creative writing Masters to get a draft finished. Now I’m in the world, a published author, but with no agent, no contract, no support structures, working full-time at home in a completely different field, living through a pandemic, with one child in secondary school and another at a COVID-ridden university, trying to keep some momentum going.

There is transition energy afoot. It’s been a fuck of(f of) a year. I’m starting my annual process of looking back, so I can look forward. I’m lucky in all the ways that matter. Writing is hard — it has always been hard — but it still feels like the most important thing I can do with my spare time. I don’t write for the pleasure of writing, but it means a lot to me, and I manage to create space in my life to do it. For that I am thankful.

Over the next few weeks, as we come to the end of 2020, everything I’ve written about here will shake out. I can’t stay still for long, although I do try. The ideal I hold in my head of a slow, loving, meaningful life always seems just out of reach, but I do my best with what I have.

I wonder what next year will bring? I wonder how I can make my craft feel more fun? With those questions in mind, we enter a season of change.

Lockdown, Part 2

Halloween has been and gone, Bonfire Night is cancelled, and I’m writing a pep talk to myself as in England we go into another lockdown. It’s shit we have to do it, but we do, and better late than never. These are tough times and these periods of isolation are hard on the spirit.

I have a novel to write, a pile of books to read, and films to watch. I also have a family with me, and I continue to do my software development job from home. This is probably the future of my line of work, which I have mixed feelings about. I’ve lost my morning cup of sanity coffee at Caffe Nero, but I’m healthy, my family are healthy, and I can pay the bills. I feel grumpily grateful.

So, do what you need to do to stay safe and sane in whatever situation you find yourself in. The world is full of good people, and this will pass.

Doctor Sleep (2019)

Director: Mike Flanagan

Danny Torrance is an alcoholic, but finds a place of peace and sobriety in New Hampshire, where he uses his psychic power, which he calls the shine, to ease the deaths of the elderly people in a local hospice. Death isn’t often realistically shown in films — not the quiet deaths, the elderly deaths, the four a.m. in an empty room, afraid and alone deaths – but in Doctor Sleep, we see final breaths leave peoples bodies. It’s shocking, because it is portrayed so simply and truthfully, but it is also life-affirming. Danny is performing the ultimate service, soothing people out of life, just as a midwife brings a baby into it.

We also see a young boy with the shine horrifically murdered by an extended family of vampire-like people, his death deliberately brutal and painful to maximise the amount of dying breath he releases, which is their food. Over several years, Danny has psychic conversations with Abra, a teenager with an incredibly strong shine who he hasn’t met. She witnesses the boy’s death. Using her power, she tracks Danny down to ask for his help, but he warns her to keep her power under wraps, like he has, because the creatures, who call themselves the True Knot, will come for her next.

Rose the Hat is an interesting villain. Her group acts like a family, with strong bonds and loyalty, and we are sympathetic to their ever-worsening hunger, even knowing they are picking off shine children across America. They are at the top of the food chain, above humans, and need to find people who are potent with the shine for nourishment. As Crow laments, children have the strongest shine, before the adult world drains them, but in the modern world technology dulls even children’s shines. When Rose senses Abra, she resolves to track her down. Danny, Abra and Rose the Hat meet for a final showdown at The Overlook, and that’s a fine finale to my 2020 #31DaysOfHorror.

Director: James Whale

The Bride of Frankenstein contains some of the most iconic images in cinema, but it opens with a scene I really didn’t expect — Lord Byron and Percy Shelley praising Mary Shelley for her book, Frankenstein. In a bold move by the film-makers, Shelley herself continues the story from the end of the 1931 film. Even this is not as bold as the little people in jars, grown by Doctor Septimus Pretorius in his attempts to create a woman, and shown to Henry Frankenstein to get him to help Pretorius’s cause. The mini king, queen, devil, and bishop caper around, providing unexpected surreal slapstick. Like the monster is made of body parts, The Bride of Frankenstein feels like it is made of several films.

Doctor Pretorius is a singularly evil presence. As Pretorius cajoles and blackmails Frankenstein into helping him in his laboratory, the monster wanders the countryside, hungry and lonely. In a famous scene, a blind old man plays the violin, attracting the monster, who is accepted into the man’s home. But the local villagers cannot let the monster alone, and he is eventually caught, but he escapes and meets Pretorius in a nearby crypt.

The final quarter dials up the suspense. The laboratory is familiar from clips played for years on television. It’s amazing to think how thoroughly Bride of Frankenstein has permeated Western popular culture. The score is simply a persistent beat, like the Bride’s heart, and it’s a fantastic touch to have the same actress play both Bride and Mary Shelley. As the Bride opens her eyes, we hear one of the most famous lines in movie history — ‘She’s alive! Alive!’.

Letterboxd: The Bride of Frankenstein (1935), dir. James Whale.

The Exorcist (1973)

Director: William Friedkin

The Exorcist is a cultural behemoth. It’s my twenty-ninth film in this year’s #31DaysOfHorror, and I’m feeling horror fatigue. The film has a weighty reputation — I’d seen clips on television, of Regan vomiting on Father Karras, and turning her head fully around, and I remembered the opening sequence in Iraq, probably from the DVD I bought but never watched to the end. I can’t remember why I didn’t watch it to the end.

It’s an astonishing film and deserves the plaudits. As I watched, the question that kept coming up in my mind was, why Regan? Father Karras asks Father Merrin that question directly, in a scene that is cut from the theatrical release. Merrin replies the point is to make humans despair and believe they are not worthy of God’s love. This is a little disingenuous. At the start of the film, Merrin uncovers relics and objects from an archaeological dig, including an image of the demon, and a catholic medal. He heads back to America, saying there is something he has to do. Later, when Karras plays the recording of Regan’s voices backwards, the demon says, ’Fear the priest. Merrin!’. This is before Father Merrin knows anything about Regan. It implies the demon has been exorcised by Merrin before, and we wonder if Merrin’s digging for relics somehow caused Regan’s possession.

These rabbit holes aside, for me this is Regan’s mother’s film. Ellen Burstyn is magnificent as Chris MacNeil. Some of the most affecting scenes are when we see her rage and fight for her daughter’s life, as well as despair and grieve for what her daughter has become. On a lighter note, when Kinderman, the detective, is trying to get Father Karras to help with his investigation (mainly by being creepy, threatening and odd), there is some high quality tennis happening on the courts behind them. I enjoyed that. That’s the power of a 4K restoration for you.