Michael Walters

Notes from the peninsula

Welcome!

This is my little word garden on the internet—Michael Walters, author (it’s true!). I have a speculative fiction novel, THE COMPLEX, out with Salt Publishing, and I’m deep in the writing of a follow-up. I would love it if you gave it a try.

I use Bluesky to connect with people, Letterboxd to track films, and StoryGraph to track books. Follow me and say hello in all those places.

And if you want more of my thoughts on writing in particular, you can subscribe to my posts on PATREON. There’s a Weird and Wonderful tier if you want to support me with a donation, and that now includes notes on the novels I’m reading, but I post regularly to all patrons.

The Mummy (1932)

Director: Karl Freund

The original Universal horror films are a bit of a blind spot for me. They weren’t on TV in our house, so I have no childhood affinity to them, and once my parents let me watch horror, I was straight into Jaws, The Car, Duel, Piranha — pacy, garish, seventies films. I didn’t go back beyond my father’s earliest favourites, which were films like Invasion of the Body Snatchers, Night of the Hunter, and Psycho.

Two years ago, I made an effort to watch Tod Browning’s Dracula and James Whale’s Frankenstein, but they were more like homework than a pleasure. However, that did mean that as soon as I heard Edward Van Sloan’s voice I saw in his Dr Muller both Van Helsing and Dr Waldman. In The Mummy, it is his belief in Egyptian magic and knowledge of ancient Egypt that keeps the colonial English heroes in the game.

Imhotep has many magical powers, including mind control. Boris Karloff’s stare is a thing to behold. Imhotep tricks the British archaeologists into digging up the tomb of his great love, the princess Anck-su-namun, and ensuring that her remains are displayed in Cairo, not London. The air of arrogant British colonialism is thick, but in this, Imhotep outsmarts the archaeologists, who it seems will do anything in the name of science. Then he goes after Helen Grosvenor, a half-Egyptian British woman in Cairo, who he believes is his love reincarnated.

I suspect with practice, or guidance, I could get more out of films from this period. I’m glad I watched it, but it’s still more like homework.

Director: Lucio Fulci

Zombies really bothered me as a kid. Seeing the insides of the human body spill out was as pure a vision of horror as I could imagine. Guts should not be outside of your body, full stop. I only watched one zombie film, whose title I can’t remember, and the ten minutes I managed of it fucked me up for weeks.

In Dunwich, Massachusetts, a priest, Father Thomas, throws a noose over a tree in a graveyard and hangs himself. This somehow opens the gates of hell. In New York, Mary has a vision of the dead priest at a seance, and collapses as if dead, only to wake up half-buried in her coffin. She is saved by Peter, a reporter, and their investigations lead them to Dunwich, where the dead priest is killing its citizens in grisly ways.

Fulci thrives on disgust and revulsion, but things take their time to get going. Characters talk directly to the camera. Bodies come and go. A dead woman moves around an artists’ house. There are close up shots of eyes. Waves of maggots. Bleeding walls. A jealous father drills the head of a boy he finds with his daughter. The images sneak up on you, then smack you in the face.

Dunwich looks suitably pre-apocalyptic, with mist, strong winds, and empty streets. Much of the population are so pale and odd, they could already by dead. The soundtrack, sound effects and suburban streets reminded me of Michael Jackson’s Thriller — it had to have been an influence. In this strange place, the dynamic of Gerry and Sandra is interesting — he is a therapist who lets his wife wander into his sessions, and Sandra is his patient who he feels free to visit in the middle of the night when she’s frightened. She is an artist and paints strange horned creatures, and monster eyes. He has odd pictures on his office wall too, possibly her work. Does he have any other patients?!

As abject as these films might seem on scuzzy VHS cassettes and tiny television screens, they are never as bad when you go back to them. Fulci sacrifices character development and story for the power of the image. By the end I felt wrung out. Nihilism is exhausting.

Letterboxd: City of the Living Dead (1980), dir. Lucio Fulci.

Blade (1998)

Director: Stephen Norrington

The opening sequence is brilliant. A woman lures a man to a party in an abattoir. It’s an aggressive crowd, and when the fire sprinklers come on, it’s not water but blood, and everyone around the man turns into a vampire. Blade arrives to kill as many vampires as he can — his raison d‘etre. It’s thrilling and weird. Vampires now own half of Manhattan. There is a vampire Bible, and a ritual to awaken a blood god. Which makes sense, right? Vampires would worship a blood god.

Blade is like a magical source of future movie ideas. The long black jacket and sunglasses, kung-fu fight sequences, being ‘the chosen one’, and even the black marble hallway fight scene can all be found in The Matrix twelve months later. The flow of blood through an elaborate ancient mechanism to bring an apocalypse appears in The Cabin in the Woods. And while Blade came first, his samurai-like lifestyle, especially the meditation joss sticks and little cushion, whilst laudible, is nowhere near as cool as Forest Whittaker in his pigeon loft in Ghost Dog. Just sayin’.

Blade is also the first of Marvel’s adult superhero films, and we are still seeing that thread unfurl. Wesley Snipes even tried to get a version of Black Panther made before he signed up for Blade. It’s a fun, if empty, blockbuster, with an amazing performance by Stephen Dorff as the baddest of the bad vampires, Deacon Frost. Blade is a hidden cultural phenomenon.

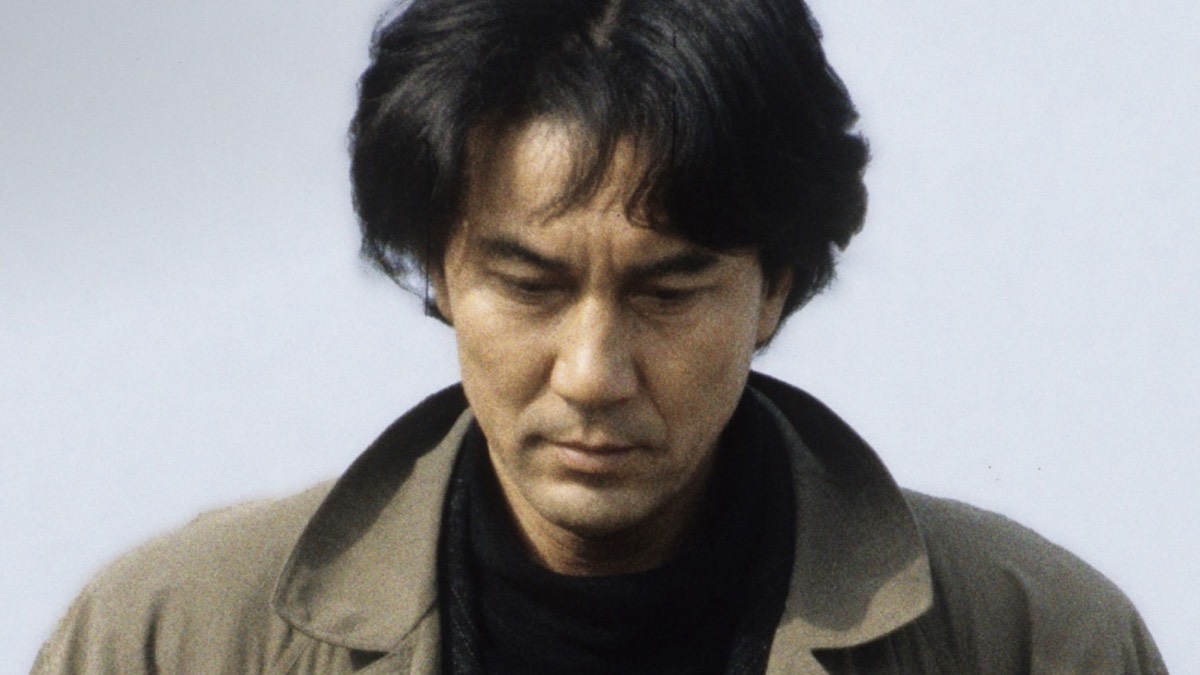

Cure (1997)

Director: Kiyoshi Kurosawa

How much control do we have over what we do? What do we ever choose to do in full consciousness? Takabe, a detective in Tokyo, investigates a series of murders, each by a different killer, but all carving a cross into their victims throats. The trail leads him to Mamiya, a man with extreme short-term memory loss. As Takabe talks with his suspect, Takabe’s world begins to crumble.

Masato Hagiwara gives a masterful performance as Mamiya, equal parts creepy, charismatic and frustrating. Once you understand what’s going on, you start to notice the small movements and seemingly inconsequential decisions he makes, and how they play in to the whole. Whenever he is with Takabe, you fear for Takabe’s sanity. Those conversations make me think of both Silence of the Lambs and Se7en. There are also stylistic choices in the film that we see again in Pulse three years later.

The less you know about this film going in, the more powerful its effect is, which is apt for the subject matter. It makes you feel deeply uncomfortable, because it shows how ordinary people can do horrific things, and rationalise it as normal. The horror is existential, and the questions it asks are philosophical. Cure is potent as hell.

Spring (2014)

Director: Aaron Moorhead and Justin Benson

If Guillermo del Toro shot a film scripted by David Cronenberg, based on a story by HP Lovecraft, then had it edited by Richard Linklater, you would get Spring. I thoroughly enjoyed Aaron Moorhead and Justin Benson’s time-puzzle film, The Endless, so I was excited for this. I was not expecting the unexpectedly strong vibes of Before Sunrise.

Evan’s mother dies, and the night after her funeral, in the bar where he works, he gets into a fight and loses his job. He has no family or girlfriend, so on a whim he uses his savings to go backpacking in Italy. In a spectacularly beautiful coastal town he meets Louise, who is not the research student she claims to be.

The Italian countryside gets under Evan’s skin, and he begins to rediscover his joie de vivre. He falls in love with Louise, but she is hiding her real form from him. The camera begins to linger on insects, worms and dead animals. Evan is still processing his mother’s passing, and while Louise might represent spring after his personal winter, she also represents death.

As much as this is a fairy tale horror romance, where the beauty is the beast, this is also a film about male relationships. Back home, Evan’s best friend is a sweetly immature stoner, and at the start of his trip in Italy, he hooks up with two amusingly awful British backpackers. Once he arrives in the Italian town, he begins to notice the old men drinking coffee and playing chess in the square, and he falls into an awkward friendship with the farmer he labours for in exchange for a room. Being in a foreign land, meeting these men, and of course Louise, allows him to get to grips with his personal crisis.

Letterboxd: Spring (2014), dir. Aaron Moorhead and Justin Benson.

Jacob’s Ladder (1991)

Director: Adrian Lyne

Jacob’s Ladder treats the subject of the Vietnam war with a little more respect than Piranha. Jacob is beset by visions and fever dreams. We constantly switch between realities, from the Vietnamese jungle, to his home in New York City, and it’s bewildering, for him and us. I often wrestle with ways of getting more fantastical imagery into my realist stories, and this film’s solution is ingenious. It has actual cool-as-hell demons in it, and it still feels art house. Tim Robbins is magnificent.

There is a shot around the halfway point of this film that made me think about the nature of film-making compared with writing prose fiction. Jacob is lying in the bath having just regained consciousness from a fever, and he realises that the wonderful dream he’s woken from was not real, and he looks so shocked and sad, I was deeply moved. One of the creative writing courses I did many years ago described how the metaphor of film can be useful in writing fiction. It advised the writer like a director and cinematographer, with scenes built of shots and cuts, with entrance and exit points, and so on. It’s only a small leap to wonder how the writer is like an actor too. Watching Jacob come out of his dream, I realised I couldn’t reproduce my experience of that image in prose. The camerawork, editing, acting, sound composition — all of it contributed. Words alone could create a different version of that image, but it would be different.

That got a bit philosophical. Anyway, the film is a masterpiece — ambitious, emotional, and beautifully constructed.

Noroi: The Curse (2005)

Director: Kôji Shiraishi

Kobayashi has such a soft face, and is kind, but he is also dogged and brave. We know from the start things will go badly for him, but we still hope he will be okay. It isn’t clear for some time what Kobayashi is investigating. This mockumentary is made from grainy handheld video and low-resolution clips of Japanese televison shows. It revels in its fragmentary, low-fi nature.

We watch video tapes, and we see video tapes passed around, as we follow Kobayashi, a paranormal investigator, with his cameraman Miyajima, around the scuzzy edges of Tokyo. There are dead pigeons on balconies and broken appliances in gardens. The pictures are often shaky and pixelated, which makes it hard to watch in places on a modern 4K screen. You feel you are watching something you shouldn’t be.

I was turned on to this by the Gaylords of Darkness, who loved this film as much as I do. The screenplay must have been a devil to put together. At the mid-point, the connections between the events become more clear, and the sense of dread increases dramatically. Like the patterns Kagutaba’s victims feel compelled to create, the narratives are weaved out of sight, and come together in the final third. This is an unsafe, unforgettable film.

Director: Peter Strickland

Another horror film that divided people, and another edge to the horror film landscape. Renowned film sound technician Gilderoy is a fish out of water in a remote Italian sound studio. He thinks the film he’s agreed to work on, The Equestrian Vortex, is about horses, but in fact is an Italian horror film about the torture of witches — although as manipulative director Francesco says, one of the women does ride a horse. He is immediately homesick. The studio staff are unhelpful, he doesn’t speak Italian, and he is socially awkward.

We never see the violence in the film he is working on, but we do see the planning sheets describing the sounds he needs to replicate. To comfort himself, he listens to tapes of sounds at his mother’s house, like her doorbell, and birdsong in her garden. He is emotionally repressed, but hypersensitive to the world around him, and a master of both the technical work of sound design, and the more practical work of making everyday objects sound like something else. Melons become chopped flesh. Ripped radish stalks are witches having their hair torn out. Gilderoy’s face is a treat as he shows a hidden sadistic pleasure to his work.

The camera lingers on objects in extreme closeups — tape reels, sound dials, gloved hands, microphones – just as it does on the actors’ faces as they dub the sounds and screams of witches and, most amusingly, the ‘dangerously aroused Goblin’. The Italian men are obnoxious, and the women suffer for it. Gilderoy is bullied into doing things he does not want to do, and his mental health suffers.

There are so many wonderful touches to this film, from the way the power keeps cutting out, to the way scenes blur seamlessly into each other. Like Knife+Heart, this film plays with form, with a film within a film, but here the film we are watching bends and loops, mirroring Gilderoy’s experience, and perhaps his desires. There are philosophical questions about how things start and when they are finished. I loved it.

Letterboxd: Berberian Sound Studio (2012), dir. Peter Strickland.

Piranha (1978)

Director: Joe Dante

Being nibbled to death by a swarm of piranha is a different agony, I imagine, to being bitten in half by a great white shark. The standard issue opening victims, David and Barbara, go swimming in a pool at a seemingly deserted top secret military compound in the middle of the night. The unfortunate Barbara jokes with David she isn’t the Creature from the Black Lagoon, just before they are both eaten alive. We cut to Maggie, the woman sent to find them, playing a Jaws video game.

This film wears its ripoff credentials on its sleeve, and matches Jaws beat for beat, from the steady stream of individual deaths, to the business-focussed mayor, to the big event in the water, even throwing in a water skiing scene à la Jaws 2. The performances are over-the-top, and the music is heavy-handed, but it’s paced perfectly, and the special effects are a minor miracle on the film’s tiny budget.

Where Jaws’ fourth of July set piece results in one death, here Dante unleashes the piranha on a summer camp of pre-teens, and in the finale, there are bloodied bodies everywhere. It’s fun, with some nicely timed comedy moments, but in truth it has a surprisingly dark heart.

Fascination (1979)

Director: Jean Rollin

Fascination is set in France, 1905, and has a fairy tale vibe, with misty countryside, a splendid French chateau, and a protagonist, Marc, who at the start steals a bag of gold. He hides at the chateau to escape his pursuers, where two women, Elisabeth and Eva, are waiting for the arrival of their marchioness. Marc is arrogant and threatening, but the two women, who are in love with each other, don’t seem bothered. When the marchioness arrives with her entourage for a party, it becomes clear Marc is a play thing for the evening, and might not leave the chateau alive.

It takes a while to get to the heart of Fascination. Marc is so unlikeable, there is a temptation to turn the film off, but once Elisabeth and Eva take the screen, it becomes clear he is not the hero of the film, which is a relief. The story is really Elisabeth’s. The women hold all the power. This is a film about power dynamics, feminism and class. In the opening scene, Elisabeth drinks ox blood at an abattoir to give herself strength. In another, Eva strides across the bridge to the chateau, naked under a black cloak, bearing down on her victim with a super-sized scythe. At the party, when it finally begins, Marc plays a game of blind man’s buff, and the women toy with him. He is dangerous, but he squanders his advantages.

It is a beautifully shot film. The allegorical elements about the aristocracy and the working class might be a little heavy-handed, but there is plenty of fun to be had once the scythe comes out, and the evening’s real game begins.