Michael Walters

Notes from the peninsula

Welcome!

This is my little word garden on the internet—Michael Walters, author (it’s true!). I have a speculative fiction novel, THE COMPLEX, out with Salt Publishing, and I’m deep in the writing of a follow-up. I would love it if you gave it a try.

I use Bluesky to connect with people, Letterboxd to track films, and StoryGraph to track books. Follow me and say hello in all those places.

And if you want more of my thoughts on writing in particular, you can subscribe to my posts on PATREON. There’s a Weird and Wonderful tier if you want to support me with a donation, and that now includes notes on the novels I’m reading, but I post regularly to all patrons.

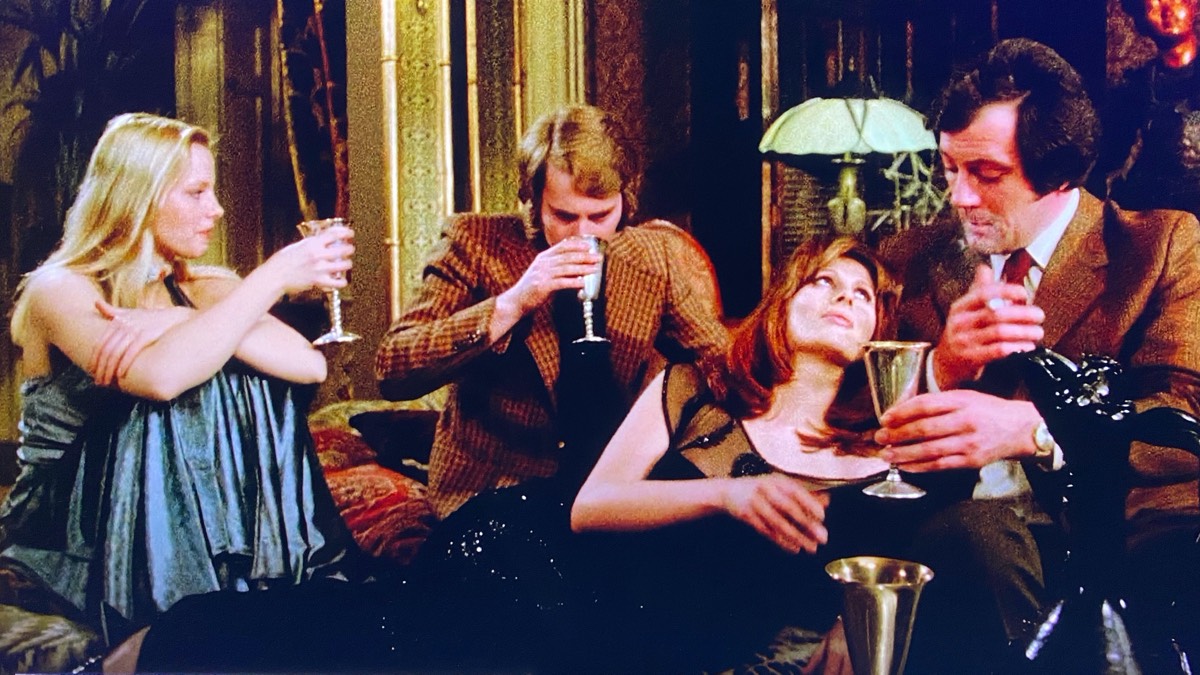

Vampyres (1974)

Director: José Ramón Larraz

I chose Vampyres, the first of my #31DaysOfHorror choices this year that I would say is exploitation cinema, naturally, because of the cover art. After the pitch perfect seventies homage of Knife+Heart, I wanted to go to the source, and having never heard of Vampyres, took the fact it’s on BFI Player as a degree of quality control. That’s how I found myself in the seventies English countryside, stuffed in the back of a cheap caravan parked in the grounds of a gothic country house.

It’s a legitimately good example of a well-made exploitation horror film. Vampires and seduction have always gone together, and the two women who live in the crumbling house lure men there to drink their blood. It reminded me of Harry Kümel’s Daughters of Darkness from two years earlier, and I wouldn’t be surprised if that was an influence. It has oodles of charm, and some memorable images. The sex is wonderfully ordinary, by which I mean the film celebrates the middle-aged naked bodies of both men and women, although you do see more of the women. It’s sleazy, with some questionably slobbery kissing techniques, but sex is integral to the story, and even with the eventual blood-letting, it has erotic moments. Older vampire Fran casts a spell on the unpleasant and aggressive Ted, a spell which might just be his inability to say no to sex, and he becomes a sort of living meal over several days.

There is another strand with a young couple, Harriet and John, in the caravan, where she turns detective, even wearing a trench coat for a key scene towards the end. All the women are hungry in this film, whether for blood or knowledge. Harriet’s curiosity leads to a surprisingly twisted, chilling finale.

Knife+Heart (2018)

Director: Yann Gonzalez

Knife+Heart (Un couteau dans le cœur) is a modern giallo film that plays out in a gay porn production company in the summer of 1979. Anne runs the company, and has broken up with her long-term partner and film editor, Lois. Their films have become stale, and Anne knows it, so when someone brutally murders one of her actors, she uses the experience as inspiration for their next film. As Anne keeps using events in real life to make the films better, her creativity draws Lois back to her, but the killer doesn’t stop claiming victims.

The kills are violent, in particular the opening, although very little is actually seen. The costumes, locations, the film stock for the porn films, the way Lois physically edits film, it all looks perfect. It may be stylised like the classic giallos of the seventies, but where the characters in those were paper thin, Anne and her company are well-written and sensitively brought to life. Vanessa Paradis as Anne is sensational, as is Nicolas Maury’s Archibald. This film company is like a family, although money is always close to the surface of their conversations, and they have a lot of sex.

I find the idea of promiscuity fascinating, not just in sex, but as a representation of abundance. Promiscuity in the projects we choose is one route out of writer’s block. All the porn actors have sex with each other for the camera and enjoy it, even if sometimes they need a little help from ‘Golden Mouth’. It’s exciting watching Anne’s creativity blossom as she rediscovers the fun in her work. She uses the bad things happening to them and turns them into art. Anne’s intuition grows in power as the film goes on.

Scenes switch between real life, the porn films and Anne’s dreams, and sometimes it can take a few seconds to know which you are watching. Some might sneer at the films she makes, but she puts her whole self into them, and as we see at the end, is more than compensated for her labour.

Director: Graham Hughes

Today, cameras are our eyes in the world, and they are no guarantee of the truth. Webcams are ubiquitous. We can all see others and be seen. Social media not only allows that, but quantifies it, and worse, monetises it. We can see how much we are being seen and, sadly, interpret it as how much we are worth.

Video blogger Graham wants to make a name for himself online. When one of his videos seems to prove ghosts exist, it goes viral. He gets the attention he craves, but there is also money to be made, and paranormal investigator Steve joins forces with him to make the most of the opportunity.

Graham and Steve are working in the attention economy. The absurdity of that becomes clear when we watch Gabrielle, who runs a channel debunking the paranormal, film an interview with Graham and Steve, while they film her filming them for their channel, and all the while she has a secret camera recording it all. Everyone has an angle. (There is an ingenious scene that plays with angles, using a 360-degree camera at an online seance.)

As Graham’s mental health deteriorates, the stakes get higher, and it feels less like a game. We are as unsure of what is really happening as he is. Unlike the isolated characters in Pulse, Graham has a channel to broadcast on. A lot has changed in twenty years, but people still feel lonely, and they want to be seen. But as both films demonstrate, so do the dead.

Pulse (2001)

Director: Kiyoshi Kurosawa

The Tokyo in Pulse is empty and eerie. People are lonely and disconnected from each other. The characters are all young and, in one way or another, alone.

We observe a man, Taguchi, in his home, through a low resolution camera of some kind, and we wonder who is watching him, apart from us. One of his work colleagues, Michi, comes to pick up a computer disk, and he hangs himself in front of her. Meanwhile, at the university, Ryosuke, a charming economics student, tries to install the internet on his PC. Something goes wrong, and he finds himself looking at someone sitting in a room through a camera, and they seem to be looking back at him.

There are cables, wires, hoses and tubes everywhere in Pulse — in the dead Taguchi’s apartment, in the classroom where the wonderful Harue offers to help Ryosuke with his Internet problem, and in the rooftop glasshouse where Michi works — but they are not connected. Screens are a perpetual threat. It’s all depressingly prescient.

Lots of unsettling things happen in the background of shots. Some of the best shocks come in deceptively simple ways. There’s a lot to think about, but it’s left to the viewer to interpret, and Kurosawa takes the story to its absolute limits. I can’t believe it’s taken me so long to watch this. It’s a masterpiece.

The Crow (1994)

Director: Alex Proyas

The montages, quick cuts and heavy metal of The Crow is a bit of a shock after the more sedate charms of The Fog. This is a none-more-gothic revenge story to complete my revenge triptych.

Eric and his fiance Shelly are murdered by a gang of men on the night before their wedding. Like Soueliman in Atlantics, and the lepers in The Fog, Eric’s soul cannot rest until he gets justice. One year later he climbs out of his grave, and a crow leads him to each member of the gang for vengeance.

There are a lot of eyes in The Crow. The gang throw Eric through an eye-like window that looks over the city. Top Dollar (the wonderful Michael Wincott radiating wrongness and oozing the worst kind of charisma) reveres eyes and removes them from his victims. Eric can see through the eyes of the crow that watched him die. The air of black magic is surprisingly disturbing, especially with the evil half-siblings, Top Dollar and Myca. Eric wants an eye for an eye.

The music and clothes make it a pure shot of nineties nostalgia. It’s an emotional film, helped by the fact it has a sense of humour. The characters and relationships are real enough to make you care. The Crow has a lot of heart. It really is top dollar.

The Fog (1980)

Director: John Carpenter

I was always going to watch The Fog at some point in these #31DaysOfHorror, but I didn’t expect it to be so soon. It was meant to be a comfort pick for later, when things usually are a little more fraught, and the 4K restoration sort of made it ‘new’. But after Souleiman and his friends came from the sea for revenge in Atlantics, The Fog was the natural next pick.

John Carpenter is one of my favourite directors, and I still haven’t seen many of his films. The Fog is an old favourite. I watched it over and over again on VHS as a kid, recorded off the television, and it embedded Adrienne Barbeau’s radio DJ, alone in a lighthouse on the edge of town, as a lifelong crush. It’s also fun to see Jamie Lee Curtis transform from the terrorised highschooler in Halloween to a horny hitchhiker happy to have sex with the crusty Tom Atkins.

The fictional Antonio Bay is either on the Oregon coast, or California, but either way it faces the Pacific. The water is just as wild and potent here as in Dakar. I had forgotten the opening quote by Edgar Allen Poe, as well as the little HP Lovecraft references to Arkham Reef and Waitely on the coastguard radio. Debra Hill, who wrote and produced The Fog, knew her horror.

It’s a tight, fast-paced film, full of clever shots and details. It starts with a twenty-minute tour-de-force of atmospheric film-making. Cinematographer Dean Cundey gives a masterclass in creating mood and tension. The 4K version is beautiful too. It’s one of those films that you only have to watch for a couple of minutes, no matter how many times you’ve seen it, and before you know it, you’ve watched it to the end.

Atlantics (2019)

Director: Mati Diop

For the second film in my #31DaysOfHorror I wanted something recent — from something old to something new. Atlantics had been on my Netflix queue for months. I knew it was a ghost story, and that it won the 2019 Cannes Film Festival Grand Prix award. It’s art house, and it’s a romance, but it’s hardly a horror film. It is, however, fascinating.

In Dakar, Senegal, on the westernmost tip of Africa, the Atlantic Ocean constantly pounds the coastline. Ada is in love with Souleiman, who is compelled by his financial situation to leave her in Dakar and set out with his friends on a boat for Spain. Dakar is a tough place to live, and there is a great deal of poverty. The economic reality for Ada is that she has to marry Omar, a wealthy businessman. Ada’s girlfriends are obsessed with money, and they think Ada is crazy for mooning after Souleiman. On her wedding night, the wedding bed catches fire, and one of her friends says she saw Souleiman in the street. That brings the police, and the mystery deepens.

The wealthy exploit the poor, mothers make their daughters marry for money, the police are corrupt, and the mixture of soothing cinematography and slow narrative pace can only partially conceal the film’s burning sense of injustice. It’s a subtle, sensual film — curtains blow in the constant breeze, glass reflects sunlight — but, the camera always returns to the sea. The sea is always there. It’s a comfort, a temptation, and in the end, a bringer of justice.

Director: Jack Arnold

I wanted to start this year’s #31DaysOfHorror with a classic. I’m trying to watch only films I haven’t seen, with one or two exceptions, and when I sorted my iTunes movie library by release year, Creature From the Black Lagoon was the oldest unwatched horror film I owned.

I knew the Creature was one of the Universal Classic Monsters. I’d heard Guillermo del Toro talk at length about how much he wanted to see the monster get the girl at the end, and how that had fed into him making The Shape of Water. I’d also listened to Mallory O’Meara talk on the Shock Waves podcast about her book on Creature designer, Milicent Patrick. I’d heard lots about the film, but never seen it for myself.

I rarely watch older films. There is so much I haven’t seen from the seventies, eighties and nineties, that I never think to go back further. I mention this because the first thing that struck me about Creature from the Black Lagoon was its gender dynamics. I still can’t decide if they were depressingly old-skool or surprisingly modern. Is Kay passive or is she actually in charge of her male relationships? Kay, her boss David, and his boss Mark, are scientists going up river into the Amazon on a geology expedition. Kay is going out with David, but used to go out with Mark. She wants David to marry her, but he doesn’t see the point. Mark starts to make moves on Kay again, and so we see Kay spend most of her time smartly, but also tragically, trying to keep them both happy. I can’t remember when I last saw two men compete so openly for a woman in a film where it wasn’t a romantic comedy.

Steven Spielberg was clearly inspired by this for Jaws — the camera shots of the woman from below, the duh-dum orchestral score, and the Creature caught in the net bending the boat’s rigging. The shark in Jaws attacks for food, although it could be a metaphor for the nuclear bombs dropped by the United States in Japan, or even the shadow of tourist capitalism in Amity. The Creature from the Black Lagoon attacks because people are afraid and attack him. The Black Lagoon as a metaphor for repressed desire is pretty on the nose.

In a beautiful sequence, Kay, wearing a white costume, swims on the surface, while the shadowy creature mirrors her in the water beneath. He seems enchanted by her. The love triangle between Kay, David and Mark, also has a mirror in the triangle between feminine, masculine and monster. Even though the film focuses on the battle between Mark, David and the Creature, this is Kay’s story, and in seeing both the egotistical Mark and the creature die, she ends the film with the wholesome commitment-phobe David. Like Guillermo del Toro, I wish she could have loved the monster instead.

Letterboxd: The Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), dir. Jack Arnold

October beckons

I love October. I love September too, but October is the favoured child. Since rediscovering my love of the spooky, eerie and horrible, I relish the enthusiasm people have this time of year to cherish the darker paths of the heart. As 2020 enters ‘awful autumn’, I wanted to reclaim my oft-distressed mind with a project that was pure fun. That’s what #31DaysOfHorror is for me. It’s fun.

I’m going to post a horror film on Twitter every day in October, culminating in Halloween (whoooOOooo!). I will also publish a short response to the film on this website. In previous years I’ve watched a film every day, but it wasn’t good for me. Even by stretching my definition of horror to the very edges of what you might think a horror film is, a film a day when you are working full-time with young kids is a lot to handle. It’s overwhelming. This year I started in early September, but I will probably have caught up with myself in the final week of October, so things might get a little hairy with the blog posts. Hopefully I’ll be in a groove by then.

So, with a hopeful heart, perhaps holding hands, we enter the lands of the dead, and we let our shadows guide us.

In the foothills

Graham Swift once said, ‘All novelists must form personal pacts with the pace of their craft.’ Now I am deep in the foothills of my second novel, that quote is a comfort, because I’d forgotten how hard it is to write fifty thousand words. (I plucked fifty thousand from the air because it feels less intimidating than eighty thousand, but of course I have no idea how long the story will end up being. So much of it is mind games. I could equally think of it is ten five-thousand-word short stories that share characters and work as a cohesive whole, but that sounds immeasurably harder.)

The pace of my craft is not as fast as my ego would like. It’s a slow journey, with many meandering paths — all necessary. I know at a rational level getting frustrated is counterproductive, but I can’t help it. Donna Tartt describes a wrong turn while writing The Goldfinch (3:50) that was eight months of work, but it gave her information she couldn’t have found out any other way. If this bit isn’t fun, you know, the writing bit, what’s the point of writing at all?

In a summer holiday spurt, I wrote just over ten thousand words. The autumn stretches ahead, with more COVID-19, the American election (which shouldn’t be my business, but is), and Brexit, all looming in my imagination. I am safe, and my family is well, for which I am grateful. I know how lucky I am. But the technology that makes working from home possible and gives me a degree of financial security, is also the source of all distractions. I must close my ears to that noise. Those ten thousand words want to become twenty thousand. I can hear them whispering. They are the signal.

If I am in the foothills of a novel, the ascent to the summit comes from following the paths marked with the golden thread. In the land of the imagination, intuition is queen. Connections are as common as spiders webs. You don’t see golden threads or spiders webs when you rush.

Hm. I didn’t see that fairy tale turn coming. So, on we go. What did the grandma say? Keep to the path.